Measure Sound Better

Blogs

A measurement microphone is not just any microphone — it is a precision acoustic sensor designed for traceable, repeatable sound pressure measurement. This guide covers how they work, the different types available, key specifications to compare, and how to select the right one for your application. What Is a Measurement Microphone? A measurement microphone is a high-precision acoustic transducer engineered to convert sound pressure into an electrical signal with known accuracy. Unlike studio or consumer microphones that are designed to make audio "sound good," a measurement microphone is designed to be truthful — its output must faithfully represent the actual sound pressure at the measurement point. The defining characteristics of a measurement microphone include: Known, stable sensitivity (expressed in mV/Pa) that can be traced to national or international standards Flat, well-characterized frequency response under defined sound-field conditions Wide dynamic range with low distortion from noise floor to maximum SPL Traceable calibration using pistonphones or acoustic calibrators Environmental stability — minimal drift due to temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure changes In practical terms, a measurement microphone is the front-end sensor of a metrology-grade measurement chain. Every specification — from the data acquisition system to the analysis software — depends on the microphone providing an accurate representation of the acoustic environment. For a deeper comparison between measurement and regular microphones, see our article: Differences Between Measurement Microphones and Regular Microphones. How Measurement Microphones Work The Condenser Principle How a condenser measurement microphone converts sound pressure into an electrical signal Nearly all measurement microphones are condenser (capacitor) microphones. The core transduction mechanism is simple but elegant: A thin metallic diaphragm is stretched in front of a rigid backplate, separated by a small air gap The diaphragm and backplate form a capacitor When sound pressure deflects the diaphragm, the gap changes, altering the capacitance With a constant charge on the capacitor, the capacitance change produces a proportional voltage change This voltage change is the microphone's output signal. A preamplifier, typically located immediately behind the capsule, converts the high-impedance signal from the capacitor into a low-impedance signal that can travel through cables to the data acquisition system. Polarization: External vs. Prepolarized Externally polarized (left) vs. prepolarized electret (right) microphone types The condenser principle requires a polarization voltage to maintain a charge on the capacitor. There are two approaches: Externally polarized microphones receive their polarization voltage (typically 200V) from an external power supply through the preamplifier. These microphones are considered the gold standard for the highest-accuracy laboratory measurements because:- The polarization voltage is stable and well-defined- No aging effects from the polarization source- Best long-term stability Prepolarized (electret) microphones use a permanently charged PTFE (Teflon) layer on the backplate to maintain polarization. Advantages include:- No external polarization supply needed — simplifies the signal chain- More resistant to humidity (no risk of charge leakage at high humidity)- Better suited for field measurements and harsh environments- Modern prepolarized microphones achieve accuracy comparable to externally polarized models FeatureExternally PolarizedPrepolarizedPolarization sourceExternal 200V supplyBuilt-in electret layerBest forLab/reference measurementsField and industrial useHumidity toleranceSensitive above ~90% RHExcellent, even in high humidityLong-term stabilityExcellentVery good (modern designs)Signal chainRequires compatible power supplyWorks with standard IEPE/ICP preamplifiers The Preamplifier The preamplifier is a critical but often overlooked component. It serves two functions: Impedance conversion: Transforms the microphone's extremely high output impedance (~GΩ) into a low impedance suitable for cable transmission Signal conditioning: Provides the power for IEPE/ICP operation or the polarization voltage for externally polarized capsules A matched microphone-preamplifier set ensures optimal performance. This is why measurement microphones are often sold as complete sets with a matched preamplifier — the combined system is calibrated and characterized as a unit. Types of Measurement Microphones Measurement microphones are classified along two primary axes: sound-field type and physical size. By Sound-Field Type The choice of microphone type depends on the acoustic environment where measurements will be taken. Free-Field Microphones A free-field microphone is designed to measure sound arriving from a single direction in an environment free of reflections (such as an anechoic chamber or outdoors). The microphone's frequency response is compensated for the acoustic diffraction effects caused by its own physical presence in the sound field. When to use: Outdoor measurements, anechoic chamber testing, source identification, environmental noise monitoring, any scenario where sound arrives predominantly from one direction. Orientation: Point the microphone directly at the sound source (0° incidence). Pressure-Field Microphones A pressure-field microphone measures the actual sound pressure at a surface or in a sealed cavity. It has the flattest possible response when the sound field is uniform across the diaphragm — which occurs in small cavities, couplers, or at surfaces where the microphone is flush-mounted. When to use: Coupler measurements (headphone and earphone testing), hearing aid testing, measurements in small cavities, flush-mounted surface measurements, acoustic impedance measurements. Orientation: The microphone diaphragm is placed at or within the measurement surface. Random-Incidence Microphones A random-incidence (diffuse-field) microphone is optimized for environments where sound arrives from all directions simultaneously — such as reverberant rooms. Its frequency response is a weighted average of responses at all angles of incidence. When to use: Reverberation chamber measurements, environmental noise in reflective spaces, any situation where sound arrives from multiple directions. Microphone TypeSound FieldTypical ApplicationOrientationFree-fieldSound from one directionOutdoor noise, anechoic testing, source IDPoint at sourcePressure-fieldUniform pressure (cavity)Coupler testing, headphones, hearing aidsFlush with surfaceRandom-incidenceSound from all directionsReverberant rooms, diffuse environmentsAny orientation Three microphone types for different acoustic environments: free-field, pressure-field, and random-incidence By Physical Size Measurement microphone capsules come in three standard sizes, each with distinct trade-offs: 1-Inch Microphones The largest standard size. High sensitivity and low noise floor make them ideal for measuring very quiet environments. Sensitivity: ~50 mV/Pa (highest) Frequency range: Up to ~8–16 kHz Best for: Low-frequency and low-level measurements, environmental noise monitoring, building acoustics Limitation: Large size limits upper frequency range due to diffraction effects 1/2-Inch Microphones The most widely used size. Offers a good balance between sensitivity, frequency range, and physical size. Sensitivity: ~12.5–50 mV/Pa Frequency range: Up to 20–40 kHz Best for: General-purpose acoustic measurements, NVH testing, product R&D, sound level meters Why it's popular: Versatile enough for most applications; fits standard sound level meter bodies 1/4-Inch Microphones The smallest standard size. Low sensitivity but the widest frequency range. Sensitivity: ~1.6–16 mV/Pa Frequency range: Up to 40–100 kHz Best for: High-frequency measurements, ultrasonic applications, small coupler measurements, acoustic array elements Trade-off: Higher noise floor requires louder sound sources for accurate measurement Size comparison: 1-inch (CRY3101), 1/2-inch (CRY3203), and 1/4-inch (CRY3401) measurement microphone capsules SizeSensitivity (typical)Frequency RangeDynamic RangeBest For1 inch50 mV/Pa4 Hz – 16 kHz15–146 dBALow-frequency, quiet environments1/2 inch12.5–50 mV/Pa3 Hz – 40 kHz16–164 dBAGeneral-purpose, NVH, SLM1/4 inch1.6–16 mV/Pa4 Hz – 100 kHz32–174 dBAHigh-frequency, ultrasonic, arrays Key Specifications Explained When comparing measurement microphones, these specifications matter most: Sensitivity Sensitivity defines how much electrical output the microphone produces for a given sound pressure. Expressed in mV/Pa (millivolts per Pascal) or dB re 1V/Pa. Higher sensitivity = better signal-to-noise ratio at low sound levels Lower sensitivity = higher maximum SPL before distortion There is always a trade-off between sensitivity and maximum SPL Frequency Response The frequency range over which the microphone provides accurate measurements, typically specified within ±2 dB or ±1 dB. The useful range depends on:- Microphone size (smaller = wider range)- Sound-field type (free-field compensation extends the useful range)- Mounting configuration Dynamic Range The span between the lowest measurable level (noise floor) and the highest level before a specified distortion threshold (typically 3% THD). A wider dynamic range means the microphone can handle a greater variety of measurement scenarios. Self-Noise (Equivalent Noise Level) The inherent electrical noise of the microphone, expressed as an equivalent sound pressure level in dBA. Lower is better — critical for measuring quiet environments. 1-inch microphones: ~15–18 dBA (quietest) 1/2-inch microphones: ~16–28 dBA 1/4-inch microphones: ~32–46 dBA Stability and Temperature Coefficient Long-term sensitivity drift and sensitivity change with temperature. Important for:- Permanent monitoring installations (fixed outdoor microphones)- Measurements in extreme environments (engine test cells, climatic chambers)- Ensuring measurement results are comparable over months or years IEC Standards Compliance Measurement microphones are classified according to IEC 61094 series:- IEC 61094-1: Primary calibration by reciprocity method- IEC 61094-4: Specifications for working standard microphones (laboratory use)- IEC 61094-5: Working standard microphones for in-situ (field) use Sound level meters incorporating measurement microphones must comply with:- IEC 61672-1: Class 1 (precision) or Class 2 (general purpose) How to Choose the Right Measurement Microphone How to select the right measurement microphone for your application Step 1: Identify Your Sound Field Your Measurement ScenarioRecommended TypeOutdoor environmental noiseFree-fieldAnechoic chamber testingFree-fieldHeadphone/earphone couplerPressure-fieldHearing aid testingPressure-fieldReverberant roomRandom-incidenceSurface-mounted on a machinePressure-fieldGeneral factory noiseFree-field or random-incidence Step 2: Determine Required Frequency Range ApplicationMinimum Frequency RangeBuilding acoustics20 Hz – 8 kHzEnvironmental noise20 Hz – 12.5 kHzGeneral acoustic testing20 Hz – 20 kHzNVH (automotive)20 Hz – 20 kHzElectroacoustic product testing20 Hz – 40 kHzUltrasonic measurements20 Hz – 100 kHz Step 3: Match the Dynamic Range to Your Environment Quiet environments (recording studios, anechoic chambers): Choose high-sensitivity microphones (50 mV/Pa, 1/2" or 1") with low self-noise Industrial environments (factory floors, engine test cells): Choose lower-sensitivity microphones (4–12.5 mV/Pa, 1/4" or 1/2") with high maximum SPL Wide-range applications: Choose microphones with the widest dynamic range available Step 4: Consider Environmental Conditions High humidity or outdoor use: Prepolarized microphones are recommended Extreme temperatures: Check the microphone's operating temperature range and temperature coefficient Dusty or wet environments: Look for IP-rated solutions (e.g., IP67 for NVH field testing) Hazardous areas: Check for ATEX/IECEx certification if required Step 5: Evaluate the Complete System A measurement microphone does not work alone. Consider:- Preamplifier compatibility: Matched sets ensure specified performance- Data acquisition system: Input impedance, voltage range, and sampling rate must match- Calibration infrastructure: Do you have access to a pistonphone or acoustic calibrator?- Software ecosystem: Can your analysis software import calibration data and apply corrections? Applications Electroacoustic Product Testing Testing loudspeakers, headphones, earphones, and hearing aids requires microphones that can accurately capture the device's frequency response, distortion, and directivity. Pressure-field microphones are used in couplers (IEC 60318 ear simulators), while free-field microphones are used in anechoic chambers. Automotive and Aerospace NVH NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) engineers use measurement microphones to characterize cabin noise, identify noise sources, evaluate sound packages, and perform transfer path analysis. Requirements include wide frequency range, high dynamic range, and robustness for field use. Environmental and Community Noise Monitoring Long-term outdoor noise monitoring stations require microphones with excellent stability over months or years, low temperature sensitivity, and tolerance to humidity, rain, and wind. Windscreens and weather protection accessories are essential. Production Line Quality Control In manufacturing, measurement microphones integrated into automated test systems verify that every loudspeaker, headphone, or microphone meets specifications before shipping. Speed, repeatability, and consistency are critical — the microphone must produce identical results across thousands of units per day. Building and Architectural Acoustics Measuring reverberation time, sound insulation, and HVAC noise requires accurate low-frequency performance and the ability to work in diffuse sound fields. Random-incidence microphones are often preferred. Acoustic Research and Standards Laboratories Primary and secondary calibration laboratories, standards organizations, and university research groups require the highest-accuracy microphones — typically externally polarized, laboratory-grade capsules calibrated by reciprocity methods. Sound Source Localization and Beamforming Microphone arrays used in acoustic cameras and beamforming systems require large numbers of measurement microphones with tightly matched sensitivity and phase response. 1/4-inch microphones are preferred for arrays due to their small size and wide frequency range. For more on acoustic imaging technology, see our guide on acoustic cameras. Noise Regulation Compliance Regulatory compliance measurements — workplace noise (ISO 9612), environmental noise (ISO 1996), product noise emission (ISO 3744/3745) — require Class 1 or Class 2 measurement microphones as specified in IEC 61672. Documentation of calibration traceability is mandatory for compliance reporting. CRYSOUND Measurement Microphone Solutions CRYSOUND's CRY3000 series measurement microphones cover the full range of sizes, field types, and applications — from laboratory reference measurements to rugged field testing. Complete Size Coverage: 1/4", 1/2", and 1" ModelSizeField TypeSensitivityFrequency RangeApplicationCRY3101-S011"Free-field50 mV/Pa4 Hz – 16 kHzLow-frequency, quiet environmentsCRY3203-S011/2"Free-field50 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 20 kHzGeneral acoustic testingCRY3261-S021/2"Free-field450 mV/Pa10 Hz – 16 kHzUltra-high sensitivityCRY3201-S011/2"Free-field12.5 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 40 kHzExtended high-frequencyCRY3401-S011/4"Free-field15.8 mV/Pa4 Hz – 40 kHzHigh-frequency testingCRY3403-S011/4"Free-field4 mV/Pa4 Hz – 90 kHzUltrasonic measurementsCRY3202-S011/2"Pressure12.5 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 20 kHzCoupler and cavity testingCRY34021/4"Pressure1.6 mV/Pa4 Hz – 100 kHzHigh-frequency pressure fieldCRY3406-S011/4"Pressure15.8 mV/Pa4 Hz – 40 kHzLow-noise pressure field CRY3213: Purpose-Built for NVH The CRY3213 NVH Measurement Microphone is specifically designed for the demanding conditions of automotive and industrial NVH testing: IP67 protection: Fully dust-tight and submersible — operates reliably in engine bays, test tracks, and climatic chambers Extended temperature range: -50°C to 125°C, covering extreme hot and cold testing scenarios Free-field response: 3.15 Hz to 20 kHz, optimized for the frequency range relevant to cabin noise, powertrain NVH, and road noise 50 mV/Pa sensitivity: High enough for quiet cabin measurements, robust enough for engine noise Matched Microphone-Preamplifier Sets Every CRYSOUND measurement microphone set includes a matched preamplifier, factory-calibrated as a complete system. This eliminates the guesswork of mixing microphones and preamplifiers from different sources, and ensures that the combined frequency response, noise floor, and dynamic range meet the published specifications. Calibration and Traceability All CRYSOUND measurement microphones ship with individual calibration certificates traceable to national standards. For ongoing measurement assurance, see our guide on measurement microphone calibration. Explore CRYSOUND Measurement Microphones → Frequently Asked Questions What is the difference between a measurement microphone and a regular microphone? A measurement microphone is designed for accuracy and traceability — its output must truthfully represent the sound pressure at the measurement point. A regular microphone is designed for audio quality, often with intentional frequency shaping to enhance speech clarity or musical timbre. For a detailed comparison, read Measurement vs. Regular Microphones. Do I need to calibrate my measurement microphone? Yes. Regular calibration — at minimum before each measurement session using an acoustic calibrator — ensures your results are accurate and traceable. Periodic laboratory recalibration (typically annually) verifies long-term stability. Learn more about microphone calibration. Can I use a 1/2-inch microphone for ultrasonic measurements? Standard 1/2-inch microphones typically reach up to 20–40 kHz, which is insufficient for many ultrasonic applications. For measurements above 40 kHz, a 1/4-inch microphone is recommended — models like the CRY3403 reach 90 kHz, while the CRY3402 reaches 100 kHz. What does "free-field" vs. "pressure-field" mean? A free-field microphone is optimized for measuring sound arriving from one direction in open space. A pressure-field microphone is optimized for measuring sound pressure in enclosed cavities or at surfaces. The difference is in how the microphone compensates for acoustic diffraction effects at high frequencies. How do I choose between externally polarized and prepolarized? For laboratory reference measurements in controlled environments, externally polarized microphones offer the best long-term stability. For field measurements, industrial applications, or environments with high humidity, prepolarized microphones are more practical and equally accurate with modern designs. What IP rating do I need for outdoor or industrial use? For NVH field testing and outdoor measurements, IP67 (dust-tight, waterproof) provides the best protection. The CRY3213 is specifically designed for these conditions. For general lab use, IP protection is typically not required. Need help selecting the right measurement microphone for your application? Contact CRYSOUND for expert guidance based on your specific measurement requirements.

Acoustic cameras turn invisible sound into visible images. This guide explains how they work, where they're used, and how to choose the right one for your application. What Is an Acoustic Camera? An acoustic camera is a device that locates and visualizes sound sources in real time. It combines a microphone array — typically 64 to 200+ MEMS microphones arranged in a specific pattern — with a video camera and signal processing software. The result is a color-coded overlay on a live video feed, showing exactly where sound is coming from and how loud it is. Think of it as a thermal camera, but for sound instead of heat. Where a thermal camera shows hot spots in red, an acoustic camera shows loud spots — pinpointing the exact location of a leak, a faulty bearing, or an electrical discharge that you can't see with your eyes. The technology was originally developed for aerospace and automotive NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) testing. Today, it has expanded into industrial maintenance, energy utilities, manufacturing quality control, and building acoustics. How Does an Acoustic Camera Work? How an acoustic camera uses beamforming: sound waves arrive at each microphone with different time delays (Δt), the processor combines all signals, and outputs a color-coded sound map. The Microphone Array At the core of every acoustic camera is a microphone array — a precisely arranged set of MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) microphones. The number of microphones directly affects performance: 64 microphones: Entry-level, suitable for general-purpose sound source localization 128 microphones: Professional-grade, better resolution and dynamic range 200+ microphones: High-end, capable of detecting subtle sources in noisy environments The spatial arrangement of these microphones matters as much as the count. Common configurations include circular, spiral (Fibonacci), and grid patterns. Each has trade-offs: spiral arrays offer good broadband performance, while grid arrays are better for near-field measurements. Beamforming: The Core Algorithm The key technology behind acoustic cameras is beamforming — a signal processing technique that combines signals from multiple microphones to "focus" on specific locations in space. Here's a simplified explanation: A sound wave arrives at each microphone at slightly different times (because each microphone is at a different distance from the source) The software calculates the expected time delay for every possible source location in the field of view For each candidate location, it shifts and sums the microphone signals according to the calculated delays Locations where the shifted signals add up constructively are identified as sound sources This process is repeated for every pixel in the image, producing a "sound map" that shows the spatial distribution of sound energy. Beamforming vs. Acoustic Holography There are two main acoustic imaging technologies: FeatureBeamformingAcoustic Holography (NAH)Best frequency rangeMid to high frequencies (>500 Hz)Low frequencies (<2 kHz)Measurement distanceFar-field (>1 meter)Near-field (<30 cm from source)ResolutionLimited by wavelength and array sizeHigher resolution at low frequenciesSpeedReal-time capableRequires careful scanningBest forLeak detection, general noise mappingEngine NVH, vibration analysis Most modern acoustic cameras use beamforming as the primary method because it works in real time and doesn't require the camera to be positioned close to the source. Some advanced systems support both technologies for maximum flexibility. The Role of the Video Camera The microphone array generates a sound map; the video camera provides the visual reference. The software overlays the sound map onto the video feed as a color-coded heat map, allowing the user to instantly see which component, pipe, or connection is producing the sound. High-end systems use depth cameras (such as Intel RealSense) to create 3D acoustic maps, enabling more accurate source localization on complex geometry. Frequency Range: Why It Matters Different applications require different frequency ranges: ApplicationTypical Frequency RangeWhyCompressed air leak detection20–50 kHzLeaks produce high-frequency hissingPartial discharge detection20–100 kHzElectrical discharges emit ultrasonic signalsMechanical fault detection1–20 kHzBearing wear, misalignment produce audible noiseAutomotive NVH100 Hz–10 kHzRoad noise, wind noise, engine noiseBuilding acoustics50 Hz–8 kHzLow-frequency structure-borne noise An acoustic camera with a frequency range of up to 100 kHz can handle virtually all industrial applications, including ultrasonic leak and partial discharge detection. Cameras limited to 20 kHz are suitable only for audible noise analysis. Key Applications Acoustic camera detecting vacuum leaks in composite materials — the color overlay pinpoints the exact leak location on the surface. Partial discharge detection on high-voltage insulators — the acoustic camera identifies discharge locations from a safe distance, combined with infrared thermal imaging for comprehensive diagnostics. 1. Compressed Air Leak Detection Compressed air is one of the most expensive energy sources in a factory. Studies show that 20–30% of compressed air is lost to leaks. An acoustic camera can scan an entire production line in minutes, identifying leaks that are invisible and inaudible to human ears. Why acoustic cameras beat traditional methods: Ultrasonic leak detectors require you to check one point at a time; an acoustic camera scans an entire area at once Visual overlay pinpoints the exact location — no guessing Many systems can estimate leak rate and annual cost, helping you prioritize repairs 2. Electrical Partial Discharge Detection Partial discharge (PD) is an early warning sign of insulation failure in high-voltage equipment — transformers, switchgear, cables, and bus bars. Left undetected, PD leads to complete insulation breakdown and potentially catastrophic failure. Acoustic cameras detect PD by capturing the ultrasonic emissions (typically 20–100 kHz) that accompany electrical discharge. The advantage over traditional PD detection methods: Non-contact: No need to de-energize equipment Real-time visualization: See exactly where the discharge is occurring Safe distance: Inspect live equipment from several meters away 3. Mechanical Fault Diagnosis Worn bearings, misaligned shafts, loose components, and valve leaks all produce characteristic sound signatures. An acoustic camera can identify and locate these faults before they lead to unplanned downtime. Common use cases: Motor and pump bearing wear detection Steam trap malfunction Valve leak identification Gearbox noise analysis 4. Automotive and Aerospace NVH Testing This is where acoustic cameras originated. NVH engineers use them to: Identify wind noise sources on vehicle bodies Locate rattles and squeaks in interior trim Analyze tire/road noise contributions Map engine noise radiation patterns Validate sound package effectiveness For NVH applications, large-aperture arrays (200+ microphones) provide the resolution needed to distinguish closely spaced sources. 5. Noise Compliance and Building Acoustics Environmental noise regulations require manufacturers to identify and reduce noise emissions. Acoustic cameras help: Map factory noise sources for compliance reporting Identify noise paths in buildings (walls, windows, HVAC) Verify effectiveness of noise barriers and enclosures 6. UAV-Mounted Acoustic Inspection A newer application: mounting acoustic cameras on drones for inspection of hard-to-reach infrastructure. Applications include: Power line and substation inspection Wind turbine blade inspection Pipeline corridor leak surveys Tall structure noise mapping Types of Acoustic Cameras Four form factors of acoustic cameras: Handheld (CRY8124), Fixed-Mount (CRY2623M), Large Array (CRY8500 SonoCAM Pi), and UAV-Mounted (CRY2626G). Handheld Acoustic Cameras Portable, battery-powered devices for field use. Typically 64–128 microphones with a built-in display. Best for maintenance rounds, leak detection, and quick inspections. Pros: Portable, easy to use, quick deployment Cons: Limited microphone count, smaller array = lower resolution at distance Fixed/Mounted Acoustic Cameras Permanently installed for continuous monitoring. Used in power substations, data centers, and critical infrastructure. Can run 24/7 with automated alerts. Pros: Continuous monitoring, automated alerting, no operator needed Cons: Fixed field of view, higher installation cost Large-Array Systems 200+ microphones on a larger frame. Used for NVH testing, pass-by noise measurement, and research applications. Often mounted on tripods or overhead structures. Pros: Highest resolution, widest frequency range, best for complex analysis Cons: Not portable, requires setup, higher cost UAV-Mounted Systems Lightweight acoustic arrays designed for drone mounting. Used for remote inspection of power lines, pipelines, and industrial facilities. Pros: Access to hard-to-reach locations, large-area surveys Cons: Flight time limits, vibration interference, regulatory requirements How to Choose the Right Acoustic Camera Quick decision guide: Choose your acoustic camera based on primary application. Step 1: Define Your Primary Application Your application determines the minimum specifications: ApplicationMin. MicrophonesFrequency RangeForm FactorCompressed air leak detection64Up to 50 kHzHandheldPartial discharge detection64–128Up to 100 kHzHandheld or fixedMechanical fault diagnosis64Up to 20 kHzHandheldNVH testing128–200+100 Hz–20 kHzLarge arrayContinuous monitoring64–128Application-dependentFixedDrone inspection64–128Up to 50 kHzUAV-mounted Step 2: Consider the Environment Noisy factory floor? You need more microphones and advanced algorithms to separate the target signal from background noise Outdoor use? Look for weather-resistant designs and wind noise rejection Hazardous area? Check for ATEX/IECEx certification Large distance? More microphones = better resolution at range Step 3: Evaluate the Software The hardware captures the data; the software turns it into actionable information. Key software features to look for: Real-time display: See the sound map live as you scan Frequency filtering: Isolate specific frequency bands to focus on particular issues Leak rate estimation: Quantify the cost of leaks in dollars or energy units Reporting: Generate professional reports with screenshots, measurements, and recommendations AI-assisted detection: Automatic identification of leak patterns and fault signatures Step 4: Compare Specifications Key specs to compare across manufacturers: SpecificationWhat It MeansWhat to Look ForMicrophone countMore mics = better resolution and sensitivity64 minimum; 128+ for demanding applicationsFrequency rangeDetermines what you can detectUp to 100 kHz for PD and ultrasonic leaksDynamic rangeAbility to measure both quiet and loud sources>70 dB for industrial environmentsAngular resolutionAbility to separate nearby sourcesSmaller is better; depends on frequency and distanceFrame rateHow quickly the sound map updates>10 fps for real-time scanningWeight and sizePortability<2 kg for handheld daily-use devicesBattery lifeRuntime for field use>3 hours for a full shift of inspectionsIP ratingDust and water resistanceIP54 or higher for industrial environments CRYSOUND Acoustic Camera Solutions CRYSOUND offers one of the widest product lines in the acoustic camera market — covering handheld, fixed-mount, large-array, and UAV-mounted form factors from a single manufacturer. Product Lineup CRY2624: 128-microphone handheld acoustic camera with ATEX certification — portable, field-ready, and safe for hazardous environments CRY8124: 200 MEMS microphones, frequency range up to 100 kHz — handles both audible noise analysis and ultrasonic applications (leak detection + partial discharge) in a single device CRY2623M: Fixed-mount version for 24/7 continuous monitoring of substations and critical infrastructure CRY8500 Series (SonoCAM Pi): Large spiral microphone array for NVH testing, pass-by noise measurement, and advanced acoustic research CRY2626G: Drone-mounted acoustic camera for remote inspection of power lines, pipelines, and wind turbines CRYSOUND acoustic camera product family: from handheld to drone-mounted solutions. Key Differentiator 1: Modular Sensor Expansion Unlike most competitors that offer a fixed-function device, CRYSOUND's acoustic cameras support external sensor modules for expanded capabilities: Infrared thermal imaging module: Combines acoustic and thermal data in a single view — when inspecting power equipment, engineers can simultaneously see the acoustic signature of partial discharge and the thermal hot spot of overheating components. This dual-mode inspection is widely used in power utilities for comprehensive substation diagnostics. IA3104 Contact Ultrasound Sensor: An external contact-type ultrasonic probe designed specifically for valve internal leak detection. The sensor couples directly to the metal surface of a valve, capturing high-frequency ultrasonic signals generated by internal leakage. Combined with intelligent analytics and guided workflows, it automates the full diagnostic process — from data acquisition to leak classification. This is critical for preventive maintenance of oil pipeline valves and natural gas network valves. This modular approach means a single CRYSOUND acoustic camera can serve as a comprehensive inspection platform, rather than requiring separate instruments for each detection task. Key Differentiator 2: Acoustic Link Mobile App CRYSOUND's Acoustic Link is a companion mobile app that connects to the acoustic camera via Wi-Fi. It enables: On-device preview: View captured photos, videos, and inspection reports on your phone or tablet — no PC required Defect-specific visualization: Retrieve gas-leak acoustic maps, partial-discharge patterns, and thermal images directly in the app One-tap sharing: Save results locally and share via the system share sheet for instant communication with colleagues and customers Automated report generation: Generate and export professional inspection reports from the field, eliminating the need to return to the office for post-processing For field inspection teams, this means faster turnaround from detection to documentation. Key Differentiator 3: Complete Acoustic Ecosystem Beyond acoustic cameras, CRYSOUND manufactures electroacoustic test systems (CRY6151B), acoustic test chambers, and calibration equipment — enabling complete acoustic testing solutions from a single vendor. With 28 years of experience and over 10,000 customers across 90+ countries, CRYSOUND brings deep domain expertise to every product. Explore CRYSOUND Acoustic Camera Products → Frequently Asked Questions What is the difference between an acoustic camera and a sound level meter? A sound level meter measures the overall sound pressure level at a single point. It tells you how loud it is, but not where the sound comes from. An acoustic camera shows both the location and the intensity of sound sources, making it far more useful for diagnosing and fixing noise problems. How far away can an acoustic camera detect a leak? Detection range depends on the leak size, background noise, microphone count, and frequency range. A typical handheld acoustic camera with 64–128 microphones can detect a 1mm compressed air leak from 10–30 meters away. Larger leaks can be detected from even greater distances. Can an acoustic camera work in a noisy factory? Yes. Modern acoustic cameras use beamforming algorithms that can isolate specific sound sources even in high-background-noise environments. The key is having enough microphones — more microphones provide better noise rejection and higher signal-to-noise ratio. Do I need training to use an acoustic camera? Basic operation is straightforward — point the camera, look at the screen, and identify the highlighted areas. Most users can start finding leaks within minutes. However, interpreting complex acoustic patterns (NVH analysis, partial discharge classification) benefits from training and experience. What is the ROI of an acoustic camera? For compressed air leak detection alone, the ROI is typically measured in months. A single quarter-inch air leak costs $2,500–$8,000 per year. Most industrial facilities have dozens to hundreds of leaks. An acoustic camera that helps you find and fix these leaks can pay for itself in the first survey. Can acoustic cameras detect gas leaks other than compressed air? Yes. Acoustic cameras can detect any pressurized gas leak that produces turbulent flow noise — including nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, natural gas, and refrigerants. The frequency characteristics may vary by gas type, but the detection principle is the same. Need help choosing the right acoustic camera for your application? Contact CRYSOUND for a personalized recommendation based on your specific requirements.

Why Choosing the Right Acoustic Test Chamber Matters In electroacoustic testing and wireless device production, the test chamber is not just a box — it directly affects measurement accuracy, throughput, and production costs. The wrong chamber can introduce background noise into your measurements, fail to shield RF interference, or simply not fit your DUT (Device Under Test). This guide walks you through the key factors for selecting an acoustic test chamber, with a comparison of CRYSOUND’s product range to help you match the right model to your application. Key Selection Criteria 1. What Are You Testing? The size and type of your DUT is the first deciding factor: DUT TypeTypical ProductsChamber RequirementSmall wireless devicesTWS earbuds, smartphones, smart watchesCompact chamber with RF shieldingMedium devicesBluetooth speakers, headphones, smart home devicesMid-size chamber with good low-frequency isolationLarge devicesLaptops, walkie-talkies, wireless serversLarge chamber with full RF shieldingUltra-quiet testingMEMS microphones, hearing aids, high-sensitivity sensorsUltra-low noise floor chamber 2. Acoustic Isolation Performance How much noise do you need to block? If your production floor is noisy (70–80 dB ambient), you need a chamber with high sound attenuation to achieve a clean measurement environment. For laboratory settings that are already relatively quiet, a lighter chamber may suffice. Key spec to check: Sound attenuation (dB) across the frequency range relevant to your product. Pay special attention to low-frequency attenuation — this is where most chambers struggle, and where the CRY725D specifically excels. 3. RF Shielding If you are testing wireless devices (Bluetooth, WiFi, GSM, WCDMA, RFID, GPS), RF shielding is essential to prevent interference between adjacent production lines. Without it, neighbouring test stations can cause false failures. Key spec to check: Shielding effectiveness (dB) at the frequencies your device operates on. 4. Door Mechanism: Pneumatic vs Manual FeaturePneumatic DoorManual DoorSpeedFast open/close, ideal for high-volume productionSlower, suitable for lab or low-volumeAutomationSerial port / PLC control, integrates into automated linesManual operation onlyConsistencyRepeatable sealing force every cycleDepends on operatorCostHigher (requires air supply)LowerBest forProduction linesR&D labs, occasional testing 5. Production Line Integration For high-volume manufacturing, consider: Drawer-style design — slides into automated test racks (e.g. CRY7865, CRY725D) Shell-type design — pairs with analysers for multi-station operation (e.g. CRY723) Serial port control — enables software-triggered open/close for fully automated test sequences CRYSOUND Acoustic Test Chamber Lineup Here is a comparison of our full product range, organised by application scenario: For Smartphones & Wireless Wearables CRY723 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Shell-type, compact form factor Best for: Smartphones, TWS earbuds, smart watches, wireless wearables Key advantage: Cost-effective and high-performance. Combine two CRY723 units with a CRY6151B analyser for complete audio, ENC, and ANC measurements — one operator manages two test stations simultaneously Door: Pneumatic CRY723D Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Enhanced version of CRY723 Best for: Wireless electronic and communication products requiring comprehensive RF testing Key advantage: Full wireless connectivity support — Bluetooth, WiFi, GSM, WCDMA, RFID, GPS Door: Pneumatic For Large Wireless Devices CRY725 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Large-format chamber Best for: Laptops, walkie-talkies, wireless servers, and other large wireless devices Key advantage: Spacious internal volume for large DUTs, compatible with comprehensive testers and vector network analysers Door: Pneumatic CRY725D Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Drawer-style, enhanced low-frequency performance Best for: Background noise measurement, applications requiring superior low-frequency isolation Key advantage: Superior soundproofing at low frequencies compared to CRY725. Combined with CRY6151B and CRY algorithm, provides enhanced noise floor minimisation for precision testing Door: Pneumatic (drawer-style) For Production Line Integration CRY7865 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Drawer-style, designed for rack integration Best for: Automated production lines testing Bluetooth headphones, speakers, laptops Key advantage: High-performance acoustic isolation and RF shielding in one unit. Drawer-style design facilitates seamless integration into automated test systems Door: Pneumatic (drawer) CRY710 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber Design: Welded steel plate construction, robust RF shielding Best for: Bluetooth, WiFi device testing where strong RF shielding is the priority Key advantage: Prevents interference between adjacent production lines. Combine two CRY710 units with a CRY6151B for quadruplex TWS headphone audio testing Door: Pneumatic (serial port controlled) For R&D and Laboratory Use CRY7413 Acoustic Test Chamber, Manual Door Design: Compact, manual door, adjustable test jig Best for: R&D labs, product development, low-volume testing Key advantage: User-friendly design with marked and adjustable test jig that accommodates various DUT sizes. Quick DUT exchange with minimal operator strain Door: Manual CRY7412 Ultra-Quiet Chamber Design: Double-shell (box-in-box), lateral two-stage opening Best for: Testing very quiet sounds — MEMS microphones, hearing aids, high-sensitivity sensors Key advantage: Unique box-in-box design provides the lowest noise floor in the product range. Essential when your DUT produces very low sound levels that would be masked by ambient noise in a standard chamber Door: Manual (two-stage lateral opening) Quick Selection Guide Your SituationRecommended ModelWhyTesting TWS earbuds on a production lineCRY723Compact, cost-effective, dual-station with CRY6151BTesting laptops or large wireless devicesCRY725Large internal volume, full RF shieldingNeed superior low-frequency isolationCRY725DEnhanced low-frequency soundproofingAutomated production line integrationCRY7865Drawer-style, RF + acoustic shieldingBluetooth/WiFi RF isolation is priorityCRY710Robust welded steel RF shieldingR&D lab, various DUT sizesCRY7413Adjustable jig, easy DUT exchangeMeasuring very quiet soundsCRY7412Double-shell, lowest noise floor Frequently Asked Questions Do I need RF shielding in my acoustic test chamber? If you are testing any wireless device (Bluetooth, WiFi, cellular), the answer is yes. Without RF shielding, wireless signals from neighbouring test stations or production equipment can cause false test failures. All CRYSOUND pneumatic chambers include RF shielding as standard. Can I use one chamber for both R&D and production? Yes, but the optimal choice differs. For R&D, flexibility and low noise floor matter most (CRY7413 or CRY7412). For production, speed and automation matter most (CRY723, CRY7865). If you need both, consider the CRY723 — it balances performance, automation capability, and cost. What is the advantage of drawer-style vs shell-type chambers? Drawer-style (CRY7865, CRY725D) slides into standard equipment racks and integrates cleanly into automated test lines. Shell-type (CRY723) opens like a clamshell for quick DUT loading and is more versatile for varied DUT shapes. Choose drawer-style for fixed production setups; shell-type for flexible or multi-product lines. How do I reduce labour costs in acoustic testing? Combine two test chambers with a single CRY6151B electroacoustic analyser. While one DUT is being tested, the operator loads the next DUT in the second chamber. This dual-station setup — supported by CRY723, CRY710, and other models — effectively doubles throughput with no additional headcount. Need Help Choosing? Every production environment is different. If you are unsure which model fits your requirements, our engineering team can help you evaluate your testing needs and recommend the right configuration. Contact CRYSOUND for a personalised recommendation based on your DUT, production volume, and test requirements.

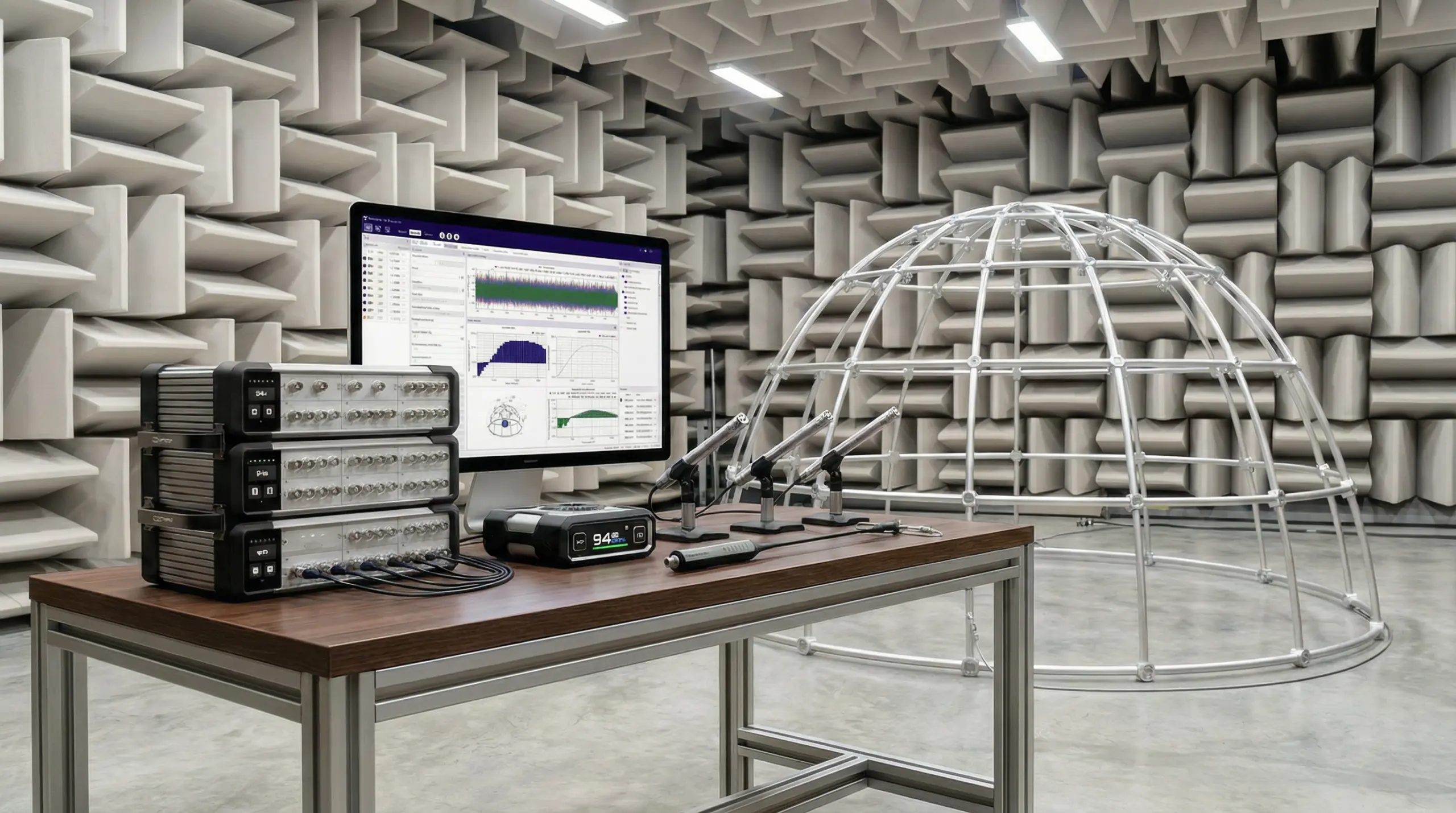

What Is an Anechoic Chamber? An anechoic chamber is a room designed to completely absorb sound reflections. The walls, ceiling, and (in a full anechoic chamber) the floor are lined with wedge-shaped foam or fibreglass absorbers that prevent sound waves from bouncing back into the room. The result is a controlled acoustic environment that simulates free-field conditions — as if the sound source were suspended in open air with no surfaces nearby. This matters because most acoustic measurements — sound power, directivity, frequency response — require a known, reflection-free environment to produce repeatable, standards-compliant results. Without it, room reflections contaminate the measurement, making results dependent on the specific room rather than the product being tested. Full Anechoic vs Semi-Anechoic (Hemi-Anechoic) Chambers Feature Full Anechoic Semi-Anechoic (Hemi-Anechoic) Absorbing surfaces All 6 surfaces (walls, ceiling, floor) 5 surfaces (walls + ceiling); floor is reflective Floor Wire mesh or perforated metal grid suspended above absorbers Solid, load-bearing concrete or steel Acoustic condition Free-field (no reflections from any direction) Free-field over a reflecting plane Load capacity Limited — cannot support heavy equipment directly Can support vehicles, machinery, industrial equipment Primary standards ISO 3745 (precision sound power) ISO 3744 (engineering sound power), ISO 3745 Typical use Microphone calibration, loudspeaker characterisation, hearing research Automotive NVH, product noise testing, industrial machinery Cost Higher (floor treatment adds significant cost and complexity) Lower (no floor treatment needed) In practice, about 80% of industrial acoustic testing uses semi-anechoic chambers because most test objects — cars, appliances, compressors, power tools — are too heavy for a suspended wire-mesh floor. What Standards Require an Anechoic Chamber? ISO 3745 — Precision Sound Power Measurement The gold standard for sound power determination. Requires either a full anechoic or hemi-anechoic chamber qualified to meet strict free-field deviation limits across the frequency range of interest. The chamber must demonstrate that the inverse-square law holds to within ±1 dB at the measurement positions. Typical cut-off frequency: 80–200 Hz, depending on chamber size and wedge depth. Below this frequency, the chamber no longer behaves as a free field. ISO 3744 — Engineering Sound Power Measurement Less stringent than ISO 3745 but still requires a hemi-anechoic environment. Allows for environmental corrections when the room is not perfectly anechoic, making it practical for production-floor test cells that approximate (but do not perfectly achieve) free-field conditions. ISO 26101 — Qualification of Free-Field Environments Defines how to verify whether a room actually meets free-field requirements. This is the standard used to “qualify” an anechoic or hemi-anechoic chamber — confirming that its acoustic performance matches what is claimed. Other Standards ECMA-74: IT equipment noise measurement (uses ISO 3745 or ISO 3744 as the underlying acoustic method) ANSI S12.55 / S12.56: North American equivalents of ISO 3744/3745 ISO 11201–11205: Various sound pressure level determination methods, some requiring free-field conditions Key Design Considerations 1. Chamber Size and Usable Volume The physical dimensions determine the lowest usable frequency. A general rule: the chamber must be large enough that the distance between the sound source and each measurement microphone is at least one wavelength at the lowest frequency of interest. For a 100 Hz cut-off, the minimum source-to-microphone distance is approximately 3.4 metres, which means the chamber’s internal dimensions (excluding wedges) should be at least 7–8 metres per side for a hemi-anechoic chamber. 2. Wedge Absorbers The depth of the absorbing wedges determines the low-frequency performance. Deeper wedges absorb lower frequencies: Wedge Depth Approximate Low-Frequency Cut-off 200 mm ~500 Hz 500 mm ~200 Hz 1000 mm ~80–100 Hz Wedge materials include melamine foam (lightweight, fire-retardant) and fibreglass (better low-frequency absorption but heavier). 3. Background Noise An anechoic chamber must also be well-isolated from external noise. The ambient noise level inside the chamber (with no source operating) should be at least 6 dB — and preferably 15 dB — below the sound pressure level generated by the test object at the measurement positions. This typically requires a chamber built with multiple layers of massive construction (concrete, steel) and vibration-isolated mounting to prevent structure-borne noise transmission. 4. Vibration Isolation For NVH testing (especially automotive), the chamber floor may include vibration-isolated foundations or air-spring mounting systems to prevent road-simulator or dynamometer vibrations from coupling into the acoustic measurement environment. What If You Do Not Have an Anechoic Chamber? Not every organisation can invest $500K–$2M+ in a purpose-built anechoic facility. Several practical alternatives exist: Sound Intensity Method (ISO 9614) Sound intensity measurements are inherently less sensitive to room reflections because intensity is a vector quantity — it distinguishes between outgoing sound (from the source) and incoming sound (reflections from room surfaces). This allows sound power determination in ordinary rooms without anechoic treatment. Trade-off: Requires specialised intensity probes and more complex measurement procedures. Acoustic Test Boxes For small products (electronics, components, transducers), a desktop-sized acoustic test box provides a controlled, low-noise environment that approximates anechoic conditions within a defined frequency range. These are significantly cheaper than a full chamber and can be placed directly on a production line. CRYSOUND offers a comprehensive range of acoustic test chambers designed for different testing scenarios: CRY723 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber — A compact, shell-type test box ideal for smartphones and wireless wearables. Combine two CRY723 units with a CRY6151B analyzer for complete audio, ENC, and ANC measurements. CRY725 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber — Designed for larger wireless devices such as laptops and walkie-talkies. Compatible with comprehensive testers and vector network analyzers. CRY7865 Pneumatic Acoustic Test Chamber — A high-performance drawer-style chamber with both acoustic isolation and RF shielding, ideal for production line audio and noise measurements of wireless electronic devices. CRY7412 Ultra-Quiet Chamber — An ultra-quiet chamber for testing very quiet sounds in noisy environments. Features a unique double-shell design for superior noise isolation. All models support pneumatic operation for fast, repeatable DUT loading on production lines — a practical alternative when a full anechoic chamber is not justified by the application. Portable Acoustic Arrays Modern acoustic imaging cameras can identify and localise noise sources in situ — in the factory, on the production line, or in the field — without any anechoic treatment. While not a substitute for standards-compliant sound power measurements, acoustic imaging enables rapid noise source diagnosis that previously required dedicated chamber time. The CRY8500 Series SonoCam Pi Acoustic Camera, is a portable acoustic imaging camera that delivers real-time sound source visualisation — ideal for R&D engineers working on noise source identification in automotive NVH, industrial equipment, and consumer electronics. In-Situ Sound Power (ISO 3744 with Corrections) ISO 3744 allows environmental correction factors to account for room reflections. If the correction is small (typically less than 2 dB), the measurement can be performed in a reasonably quiet industrial space without a purpose-built chamber. The SonoDAQ Pro data acquisition system combined with OpenTest software supports automated sound power calculations with environmental corrections built in — enabling standards-compliant measurements without a dedicated anechoic chamber. Frequently Asked Questions How much does an anechoic chamber cost? Costs vary widely based on size, performance requirements, and cut-off frequency. A small hemi-anechoic room for component testing may start around $100K–$300K, while a large automotive-grade full anechoic chamber can exceed $2M. For smaller products, acoustic test boxes offer similar isolation at a fraction of the cost. What is the difference between an anechoic chamber and a soundproof room? A soundproof room blocks external noise from entering but does nothing about internal reflections. An anechoic chamber both blocks external noise and absorbs internal reflections, creating a free-field environment for precision measurement. Can I do acoustic testing without an anechoic chamber? Yes. Depending on your application, alternatives include acoustic test boxes for small products, sound intensity methods (ISO 9614), portable acoustic imaging cameras like the CRY8500 SonoCam Pi, and in-situ measurements with environmental corrections using systems like SonoDAQ Pro. What frequency range does an anechoic chamber cover? The usable frequency range depends on the wedge depth and chamber dimensions. Most chambers are effective from their cut-off frequency (typically 80–200 Hz) up to 20 kHz or beyond. Below the cut-off, the chamber no longer provides adequate absorption. How is an anechoic chamber qualified? Chamber qualification follows ISO 26101, which verifies that the inverse-square law (sound pressure decreasing by 6 dB per doubling of distance) holds within specified tolerances at the measurement positions. Conclusion Anechoic chambers remain the gold standard for precision acoustic measurement — but they are not the only option. Understanding what your application truly requires helps you choose the right solution, whether that is a full anechoic room, a compact acoustic test chamber, or an in-situ measurement approach. At CRYSOUND, we provide the full spectrum: from purpose-built anechoic chambers to portable acoustic test boxes and advanced measurement systems — so you can get accurate results regardless of your facility constraints. Contact us to discuss which solution fits your testing requirements.

During pilot production and production line ramp-up, many issues do not appear in the way teams initially expect. Sometimes it starts with a small fluctuation at a test station, or a comment from a line engineer saying, "This result looks a bit unusual."However, when takt time, yield targets, and delivery milestones are all under pressure, these seemingly minor anomalies can quickly be amplified and begin to affect the overall production rhythm. We have been working with Huaqin as a long-term partner. As projects progressed, the challenges encountered on the production line became increasingly complex. On site, our role gradually extended from basic production test support to problem analysis and cross-team coordination during pilot production. In many cases, the focus was not simply on whether a test station was functioning, but on how to absorb uncertainties early and prevent them from disrupting delivery schedules. The following two experiences both took place during the pilot production phase of Huaqin projects. They are not exceptional cases. On the contrary, they represent the kind of everyday issues that most accurately reflect the realities of production line delivery. Airtightness Testing Issues in Project α During the pilot ramp-up of Project α, the airtightness test station for the audio microphone showed clear instability. For the same batch of products, pass rates fluctuated noticeably across repeated tests, frequently interrupting the station's operating rhythm. Initial troubleshooting naturally focused on the test system itself, including software logic, equipment status, and basic parameter settings. It soon became clear, however, that the issue did not originate from these areas. As on-site verification continued, we gradually confirmed that the anomaly was more closely related to the product's mechanical structure and material characteristics. This model used a relatively uncommon combination of materials. A sealing solution that had worked well in previous projects could not maintain consistency during actual compression. Even slight variations in applied pressure were enough to influence test results. Once the direction of the problem was clarified, the on-site approach shifted accordingly. Rather than repeatedly adjusting the existing solution, we returned to verifying the compatibility between materials and structure. Over the following period, we worked together with the customer's engineering team on the production line, testing multiple material options. This included different types of silicone and cushioning materials, variations in silicone hardness, and adjustments to plug compression methods. Each step was evaluated based on real test results before moving forward. The process was not fast, nor was it particularly clever. In essence, it came down to repeatedly confirming one question: could this solution run stably under real production line conditions?Ultimately, by introducing a customized soft silicone gasket and making fine parameter adjustments, the airtightness test results gradually stabilized. The station was able to run continuously, and the pilot production rhythm was restored. Figure 1. Test Fixture Diagram Noise Floor Issues in Project β Compared with the airtightness issue in Project α, the noise floor anomaly encountered during pilot production in Project β was more complex to diagnose. During headphone pilot production for Project β at Huaqin's Nanchang site, the noise floor test station repeatedly triggered alarms. Test data showed that measured noise levels consistently exceeded specification limits, significantly impacting the pilot production schedule. This model used high-sensitivity drivers along with a new circuit design, making the potential noise sources inherently more complex. It was not a problem that could be resolved by simply adjusting a single parameter. Rather than focusing solely on the test station, we worked with the customer's audio team to investigate the issue from a system-level signal chain perspective. The process involved sequentially testing different shielding cables, adjusting grounding strategies, evaluating various Bluetooth dongle connection methods, and isolating potential power supply and electromagnetic interference sources within the test environment. Through continuous spectrum analysis and comparative testing, the scope of the issue was gradually narrowed. It was ultimately confirmed that the elevated noise floor was primarily related to power interference from the Bluetooth dongle, combined with differences in product behavior across operating states. After this conclusion was reached, relevant configurations were adjusted and validated on site. As a result, noise floor measurements returned to a stable and controllable range, allowing pilot production to proceed. Figure 2. Work with the customer engineer to solve problems Common Characteristics of Pilot Production Issues Looking back at these two pilot production experiences, it becomes clear that despite their different manifestations, the underlying diagnostic processes were quite similar. Whether dealing with airtightness instability or excessive noise, the root cause could not be isolated to a single module. Effective resolution required on-site evaluation across mechanical structure, materials, system operating states, and test conditions. During pilot production, issues of this nature rarely come with ready-made answers. They are also unlikely to be resolved through a single verification cycle. More often, progress is made through repeated trials, comparisons, and eliminations, gradually converging on a solution that is genuinely suitable for long-term production line operation. Production line delivery rarely follows a perfectly smooth path. In many cases, what ultimately determines whether a project can move forward as planned are those unexpected issues that must be addressed immediately when they arise. In our long-term collaboration with customers, our work often takes place at these critical moments—working alongside engineering teams to stabilize processes, maintain momentum, and keep projects moving forward step by step. If you also want CRYSOUND to support your production line, you can fill out the Get in Touch form below.

In our previous blog post, "Abnormal Noise Detection: From Human Ears to AI"we discussed the key pain points of manual listening, introduced CRYSOUND's AI-based abnormal-noise testing solution, outlined the training approach at a high level, and showed how the system can be deployed on a TWS production line. In this post, we take the next step: we'll dive deeper into the analysis principles behind CRYSOUND's AI abnormal-noise algorithm, share practical test setups and real-world performance, and wrap up with a complete configuration checklist you can use to plan or validate your own deployment. Challenges Of Detecting Anomalies With Conventional Algorithms In real factories, true defects are both rare and highly diverse, which makes it difficult to collect a comprehensive library of abnormal sound patterns for supervised training. Even well-tuned—sometimes highly customized—rule-based algorithms rarely cover every abnormal signature. New defect modes, subtle variations, and shifting production conditions can fall outside predefined thresholds or feature templates, leading to missed detections (escapes). In the figure below, we compare two wav files that we generated manually. Figure 1: OK Wav Figure 2: NG Wav You can see that conventional checks—frequency response, THD, and a typical rub & buzz (R&B) algorithm—can hardly detect the injected low-level noise defect; the overall curve difference is only ~0.1 dB. In a simple FFT comparison, the two wav files do show some discrepancy, but in real production conditions the defect energy may be even lower, making it very likely to fall below fixed thresholds and slip through. By contrast, in the time–frequency representation , the abnormal signature is clearly visible, because it appears as a structured pattern over time rather than a small change in a single averaged curve. Figure 3: Analysis results Principle Of AI Abnormal Noise Algorithm CRYSOUND proposes an abnormal-noise detection approach built on a deep-learning framework that identifies defects by reconstructing the spectrogram and measuring what cannot be well reconstructed. This breaks through key limitations of traditional rule-based methods and, at the principle level, enables broader and more systematic defect coverage—especially for subtle, diverse, and previously unseen abnormal signatures. The figure below illustrates the core workflow behind our training and inference pipeline. Figure 4: Algorithm Flow Principle During model training, we build the algorithm following the workflow below. Figure 5: Algorithm Judgment Principle How To Use And Deploy The AI Algorithm Preparation First, prepare a Low-Noise Measurement Microphone / Low-noise Ear Simulator and a Microphone Power Supply to ensure you can capture subtle abnormal signatures while providing stable power to the mic. Figure 6: Low-Noise Measurement Microphone Next, you'll need a sound card to record the signal and upload the data to the host PC. Figure 7: Data Acquisition System Third, use a fixture or positioning jig to hold the product so that placement is repeatable and every recording is taken under consistent conditions. Finally, ensure a quiet and stable acoustic environment: in a lab, an anechoic chamber is ideal; on a production line, a sound-insulation box is typically used to control ambient noise and keep measurements consistent. Figure 8: Anechoic Room Figure 9: Anechoic Chamber Model Development First, create a test sequence in SonoLab, select "Deep Learning" and apply the setting. Next, select the appropriate AI abnormal-noise algorithm module and its corresponding API Figure 10: Sequence Interface 1 Then open Settings and specify the model type, as well as the file paths for the training dataset and test dataset. Click Train and wait for the model to finish training (Training time depends on your PC's hardware) Figure 11: Sequence Interface 2 During training, the status indicator turns yellow. Once training is complete, it switches to green and shows a "Training completed" message. Figure 12: Sequence Interface 3 Finally, place your test WAV files in the specified test folder and run the sequence. The model will start automatically and output the analysis results. Test Case Figure 13:Test Environment Figure 14:Test Curve System Block Diagram Figure 15: System Block Diagram 1 Figure 16: System Block Diagram 2 Equipment More technical details are available upon request—please use the "Get in touch" form below. Our team can share recommended settings and an on-site workflow tailored to your production conditions.

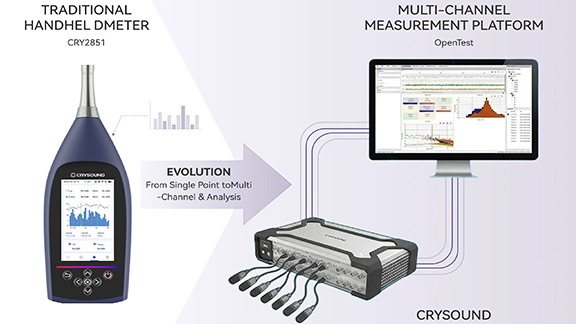

As A²B microphones and sensors are increasingly adopted in automotive applications, the demand for reliable testing in both R&D and production is also growing. This article explains why A²B testing matters, highlights the advantages of A²B over traditional analog cabling in terms of interconnect and scalability, outlines key measurement KPIs (such as frequency response, THD+N, phase/polarity, and SNR), and presents a typical test-bench setup along with the corresponding solution configuration. Why A²B Microphone and Sensor Testing Matters In-cabin audio is no longer just "music playback". Modern vehicles depend on high-performance acoustic sensing for hands-free calling, in-cabin communication, voice assistants, ANC/RNC, and more—and these features increasingly rely on multiple microphones and even accelerometers deployed around the cabin. ADI notes that the rapid expansion of audio-, voice-, and acoustics-related applications is a key trend, and that new digital microphone and connectivity approaches are enabling broader adoption. To deliver consistent performance, teams need a test workflow that is repeatable across different node positions, harness lengths, and configurations—without turning every debug session into a custom project. The Interconnect Shift: From Shielded Analog Cables to Digital A²B Historically, scaling microphone counts often meant scaling shielded analog cabling, which adds weight, cost, and integration burden—sometimes limiting these features to premium vehicle segments. A²B (Automotive Audio Bus) addresses that interconnect problem by enabling a scalable, networked digital audio architecture with deterministic behavior—exactly what timing-sensitive acoustic applications need. Figures a and b show how such a design may be realized with the traditional analog and the digital A²B systems, respectively. Figure 1 (a) Analog system design with analog mic elements (shielded wires). (b) Digital system design with digital mic elements (A²B technology and UTP wires). What You'll Measure: Key A²B Microphone KPIs Frequency Response (FR) THD+N Phase / polarity (and channel-to-channel consistency for arrays) SNR AOP (if required by your program/spec) Typical Block Diagram-What the Bench Looks Like At CRYSOUND, we provide more than just the CRY580 A²B interface. We offer a full automotive audio testing solution, including audio acquisition cards, microphones and sensors, acoustic sources, custom fixtures, acoustic test boxes, and vibration shakers, delivering a complete and streamlined testing experience. Figure 2 Here's a description of the testing block diagram, including the use of the latest OpenTest Audio Test & Measurement Software https://opentest.com Solution BOM List The value of end-to-end delivery: reducing system integration time and minimizing coordination costs between multiple suppliers. We cover everything from R&D to production line testing. Figure 3 BOM list of the solution If you'd like to learn more about A²B testing, please fill out the Get in touch form below and we'll reach out shoutly.

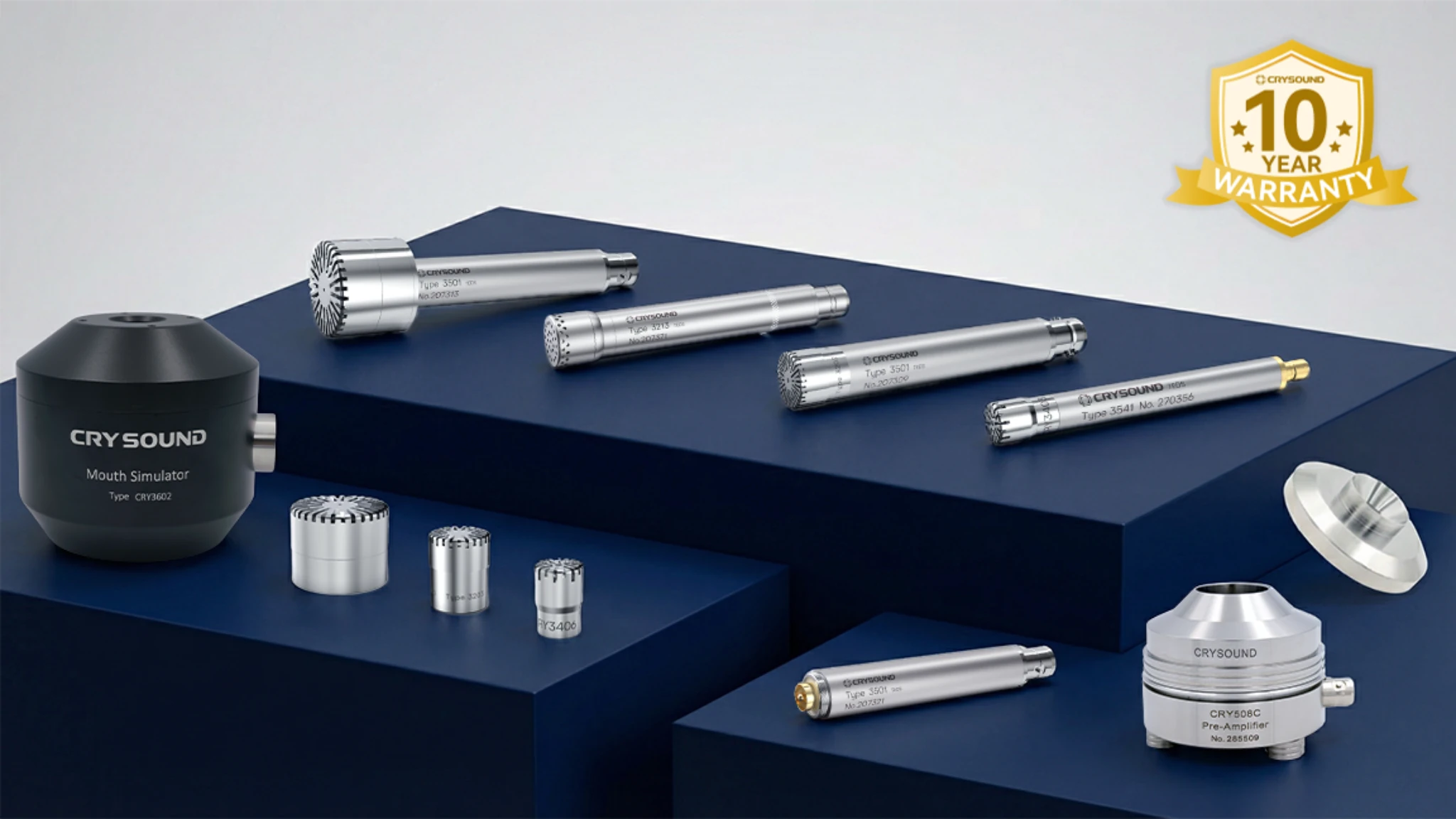

Precision measurement is only as trustworthy as the tools behind it. At CRYSOUND, long-term reliability has always been part of how we support professional acoustic testing and metrology work—especially for equipment expected to perform consistently over many years. That’s why CRYSOUND provides a 10-Year Limited Warranty for eligibleCRY3000 series sensors offering long-horizon confidence for labs, manufacturers, and audio professionals who depend on stable performance. What the 10-year warranty covers This is a limited warranty focused on defects in materials or workmanship that occur under normal use, installation, and maintenance conditions. It is not a guarantee of fitness for a specific purpose. Eligible product categories (CRY3000 Series) The 10-year limited warranty applies to the following CRY3000 Series categories (traceable by product nameplate/serial number):Microphones Preamplifiers Microphone Sets Mouth Simulators Ear Simulators Ear Simulator Sets. Warranty term: 10 years (and what’s different) For the main product categories above, the warranty term is 10 years.Accessories/consumables (e.g., windscreens, cables, adapters, seals, replaceable pinnae, packaging) are covered under a 6-month warranty unless otherwise specified by contract or separate terms. When the warranty period starts The warranty period is calculated from the shipping/delivery date. If that date is unavailable, it is calculated from the end-user purchase date (with contract proof). If valid proof cannot be provided, CRYSOUND may use the factory date or the latest traceable serial-number record as the basis. What CRYSOUND will do for eligible defects If CRYSOUND confirms the issue is covered, we may provide one or more of the following: Free repair, including necessary parts and labor Replacement with the same model, or a model of equal or higher performance (new or certified refurbished/remanufactured) Customized/project products follow contract terms Repairs or replacements do not extend the original warranty period. Clear boundaries (typical exclusions) As a limited warranty, it excludes issues caused by misuse, drops/crushing, liquid ingress, corrosive environments, out-of-spec power/ESD/surge, improper installation/grounding/sealing/maintenance, unauthorized disassembly/modification, missing/altered serial numbers, normal wear/cosmetic changes, shipping/storage mishandling, or third-party compatibility problems (where applicable). Calibration note (important for metrology users) Because microphones and simulators are metrology instruments, slight drift can occur due to environment and measurement uncertainty. Unless drift is confirmed to be caused by a manufacturing defect, calibration/recalibration and certificate updates are typically not included for free (paid calibration/verification services may be available). Service logistics (shipping & service location) For in-warranty cases, users typically cover round-trip shipping to CRYSOUND/authorized service points. Cross-border service may involve duties or customs clearance fees unless otherwise agreed by contract. CRYSOUND will arrange the nearest service option based on region, product type, and spare-part availability. Warranty & Support To request warranty service or technical support, contact info@crysound.com (or reach out to your CRYSOUND sales contact). See the warranty policy on our website: https://www.crysound.com/warranty/