Measure Sound Better

Browse Authors

Blogs

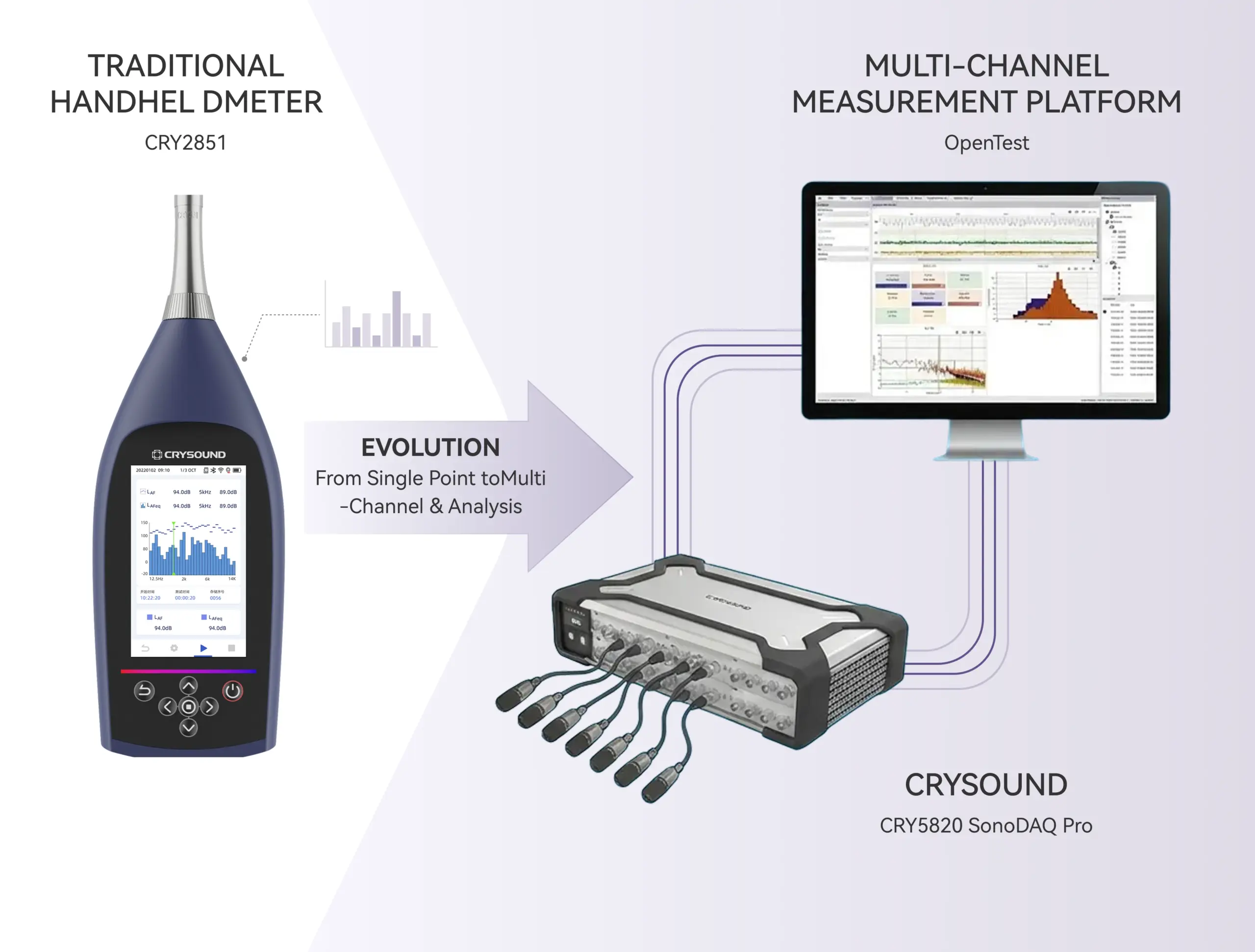

This article introduces how to build a multi-channel sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672-1 using OpenTest, in combination with SonoDAQ data acquisition hardware and measurement-grade microphones. The system supports A / C / Z frequency weighting, F / S / I time weighting, and standard acoustic quantities such as Lp, Leq, and Ln, making it suitable for a wide range of applications including environmental noise, product noise, and automotive NVH testing. From Handheld Sound Level Meters to Multi-Channel Sound Level Measurement Platforms In acoustics and vibration testing, one fundamental question appears in almost every project: “How loud is it?” From office equipment and household appliances to automotive NVH and industrial machinery, regulations, standards, and internal quality criteria all rely on quantitative evaluation of Sound Pressure Level (SPL). Traditionally, this is done using a handheld sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672, placed at a specified position to read an A-weighted sound level for compliance checks and quality verification. IEC 61672 defines detailed requirements for sound level meters in terms of frequency weighting, time weighting, linearity, self-noise, and dynamic range, and classifies instruments into Class 1 and Class 2, with Class 1 having stricter requirements and being suitable for laboratory and type-approval testing. As product structures and test requirements evolve, engineers increasingly expect more than what a single handheld meter can offer: Measure multiple positions simultaneously to compare different locations or operating points Combine sound level data with spectra and octave-band analysis to quickly identify problematic frequency regions Synchronize sound level measurement with speed, vibration, temperature, and other physical quantities for NVH diagnostics Integrate sound level measurement into automated and batch test workflows, rather than relying on manual spot checks This leads to the demand for multi-channel sound level meters: systems that not only meet IEC 61672-1 Class 1 accuracy requirements, but also provide multi-channel capability, scalability, and automation. OpenTest, developed by CRYSOUND, is a new-generation acoustic and vibration test platform. Its dedicated Sound Level Measurement module, combined with CRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro front-end hardware and measurement microphones, enables multi-channel sound level measurements consistent with Class 1 sound level meters. Figure 1. From handheld sound level meters to multi-channel sound level measurement platforms IEC 61672: What Are We Actually Measuring? Meaning of Sound Pressure Level (Lp) Sound Pressure Level (SPL) is a logarithmic measure of the root-mean-square sound pressure prms relative to the reference pressure p0, which is 20 μPa in air, defined as: When prms=1 Pa, the SPL is approximately 94 dB, which is why 94 dB / 1 kHz is commonly used as the reference level for acoustic calibrators. Frequency Weighting: A / C / Z Human hearing sensitivity varies with frequency. IEC 61672 requires all sound level meters to support A-weighting, while Class 1 instruments must also support C-weighting. Z-weighting (Zero weighting, i.e. flat response) is optional. A-weighting (dB(A))Based on the 40-phon equal-loudness contour, with significant attenuation at low and very high frequencies. It is widely used in regulations and standards as an indicator correlated with perceived loudness. C-weighting (dB(C))Much flatter than A-weighting, with less low-frequency attenuation. It is suitable for evaluating peak levels, mechanical noise, and high-level events. Z-weighting (dB(Z))Essentially flat within the specified bandwidth, preserving the original spectral energy distribution, and useful for detailed analysis. While A-weighting dominates regulations, it is not a perfect psychoacoustic model. In cases involving strong low-frequency content, modulation, or tonal components, A-weighted levels may underestimate perceived annoyance.For design and diagnostic work, it is therefore recommended to combine C/Z weighting, octave-band spectra, and sound quality metrics. Time Weighting: Fast / Slow / Impulse IEC 61672 defines the following time weightings: F (Fast): time constant ≈ 125 ms, suitable for rapidly fluctuating sound levels S (Slow): time constant ≈ 1 s, suitable for observing overall trends I (Impulse): designed for impulsive signals, more sensitive to short-duration peaks Common sound level descriptors include: LAF / LAS / LAI: A-weighted sound levels with Fast / Slow / Impulse time weighting LCpeak: C-weighted peak sound level Energy-Based and Statistical Quantities: Leq, SEL, Ln IEC 61672 also defines commonly used acoustic quantities: Leq,T / LAeq,TEquivalent continuous sound level over a time period T, widely used in environmental and product noise evaluation. Sound exposure and sound exposure level: E, LE / LAE (SEL)Represent the total sound energy of an event, commonly used for aircraft, traffic, and single-event noise evaluation. Lmax / Lmin: Maximum and minimum sound levels under a specified time weighting Lpeak (typically LCpeak): Peak sound level based on peak sound pressure Statistical levels Ln (L10, L50, L90, etc.)Levels exceeded for n% of the measurement time, commonly used in environmental noise analysis. Band Levels: Octave and 1/3-Octave Bands Although octave-band filters are specified in IEC 61260, IEC 61672 aligns with them in terms of frequency response and standard center frequencies. Common analyses include: 1-octave band levels (e.g. 31.5 Hz–16 kHz) 1/3-octave band levels, offering finer frequency resolution for identifying narrow-band noise and structural resonances Together, these quantities define the full scope of sound level measurement—from instantaneous readings to time-averaged values, and from broadband levels to frequency-resolved analysis. Sound Level Measurement with OpenTest Setup: Building the Signal Chain from Source to Software Hardware Preparation Data acquisition front-endFor example, CRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro, a modular multi-channel data acquisition system supporting 4–24 channels per unit and scalable to thousands of channels. It features 32-bit ADCs, up to 170 dB dynamic range, 1000 V channel isolation, and ≤100 ns PTP/GPS synchronization accuracy, suitable for both laboratory and field acoustic and vibration testing. SensorsOne or more measurement-grade microphone sets (with preamplifiers), positioned at representative measurement or listening locations. Computer and softwareA PC with OpenTest installed and the Sound Level Measurement module licensed. Connecting Devices and Channels in OpenTest Launch OpenTest and create a new project. In Hardware Settings, click “+”; available devices (including those connected via openDAQ or ASIO) are automatically detected. Select the required acquisition devices (e.g. SonoDAQ) and add them to the project. In Channel Settings, add the microphone channels and configure sampling rate and input range. At this point, the signal chain Sound source → Microphone → DAQ → OpenTest is fully established. Calibration: Setting the Acoustic Reference To ensure absolute accuracy, each channel must be calibrated using a Class 1 acoustic calibrator. Open the Calibration dialog in OpenTest. Select the microphone channels to be calibrated. Mount the calibrator on the microphone and start calibration. Once the reading stabilizes, complete the calibration. OpenTest automatically updates the channel sensitivity so that the 94 dB SPL reference point is aligned. For comparison tests, a handheld sound level meter (e.g. CRY2851) can be calibrated using the same calibrator (e.g. CRY3018) to ensure both systems share the same acoustic reference. Measurement: Acquiring Sound Level Time Histories Switch to the Sound Level Meter module in OpenTest and select: Measurement channels Quantities to compute (Lp, Leq, Ln, etc.) Frequency weighting (A / C / Z, computed simultaneously) Typical operating conditions may include: Idle Typical load Full load For each condition: Stabilize the DUT at the target operating state. Start measurement in OpenTest. Monitor sound level time histories, octave-band plots, and FFT spectra in real time. Stop after sufficient duration and name the dataset accordingly. Each measurement is automatically saved as a dataset for later comparison and analysis. Figure 2. Multi-channel sound level measurement using OpenTest Reporting: From Data to Traceable Documentation After measurements, OpenTest’s reporting function can be used to generate structured reports: Project information, DUT details, operating conditions Selected acoustic quantities (Leq, Lmax, LCpeak, Ln, etc.) Company logo and test personnel information Raw waveforms and analysis results can also be exported for archiving or further processing. Figure 3. OpenTest sound level measurement report Comparison with CRY2851 Handheld Sound Level Meter CRY2851 is a Class 1 sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672-1:2013, supporting A/C/Z weighting, F/S/I time weighting, and a full set of acoustic parameters. Comparison procedure: Environment and operating conditionsLow-background laboratory or semi-anechoic room; multiple operating states. Calibration consistencyBoth systems calibrated with the same Class 1 calibrator (94 dB or 114 dB at 1 kHz). Sensor placement and acquisitionMicrophones positioned as closely as possible at the same measurement point. Result comparisonCompare LAeq, LAF, LCpeak, and other key parameters under identical weighting and time windows. Figure 4. CRY2851 vs. OpenTest multi-channel sound level measurement Typical Applications of the Sound Level Measurement Module Consumer Electronics / IT Equipment Evaluate the impact of cooling strategies on LAeq and LAFmax Combine sound level limits with sound power measurements Integrate FFT, 1/3-octave, and sound quality metrics Automotive NVH / Interior Acoustics Multi-position sound level measurement in the cabin Comparison across driving conditions Coupling with order analysis and sound quality modules Household Appliances and Industrial Machinery Supplement sound power tests with multi-point sound level monitoring Integrate into production lines using sequence mode Identify problematic frequency bands via 1/3-octave analysis Environmental and Long-Term Monitoring Multi-point statistical sound level evaluation (L10, L50, L90) Long-term data logging and remote access If you are already familiar with handheld sound level meters, the OpenTest Sound Level Measurement module effectively upgrades them into a system that is: Multi-channel Traceable (raw data + analysis + reports) Expandable, working seamlessly with sound power, sound quality, FFT, and octave-band analysis modules, and supporting automated test workflows. Welcome to fill in the form below ↓ to contact us and book a demo and trial of the OpenTest Sound Level Meter module. You can also visit the OpenTest website at www.opentest.com to learn more about its features and application cases.

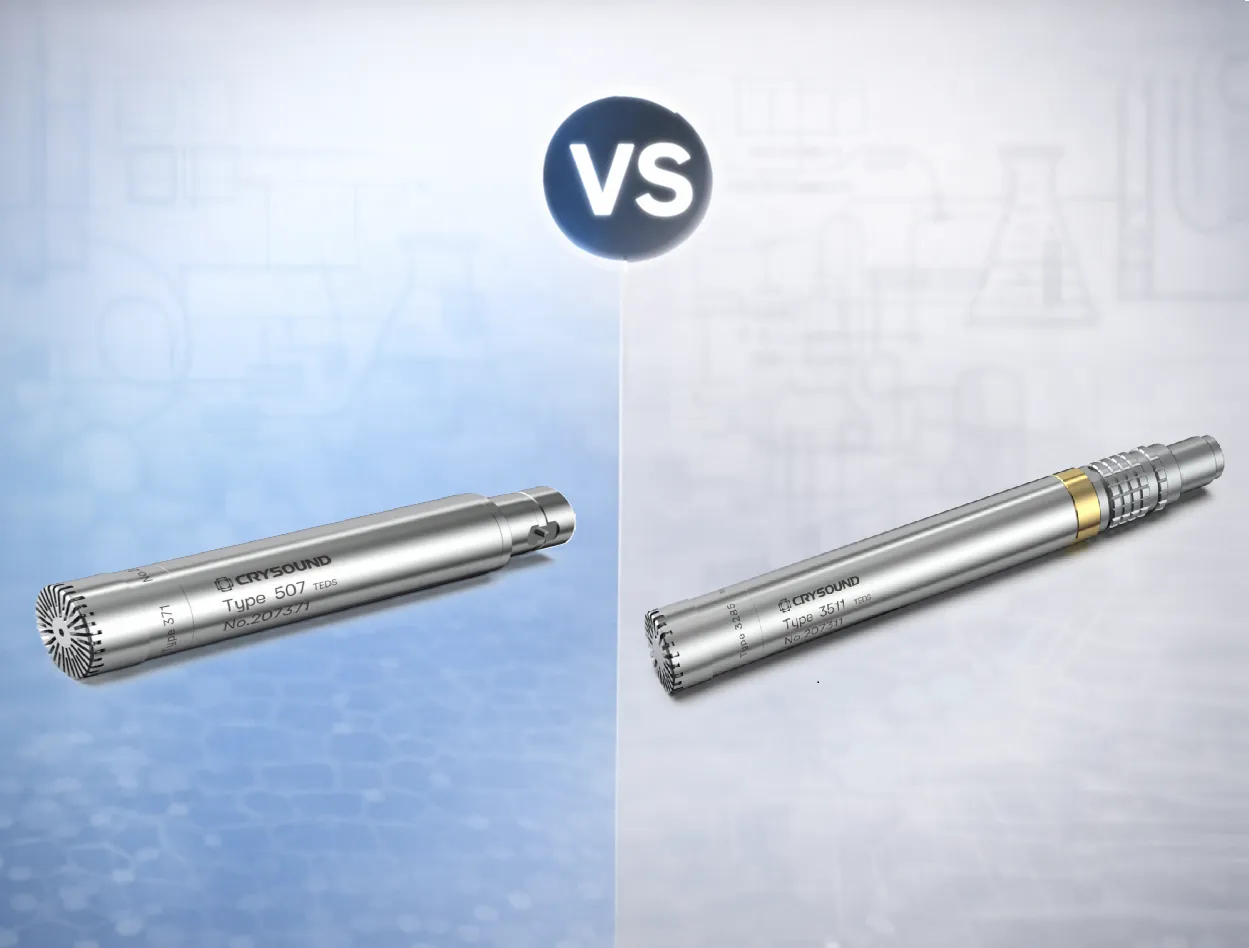

In acoustic testing, acoustic metrology, and product noise evaluation, the term measurement microphone typically refers to a condenser measurement microphone. Its signal generation relies on a polarization electric field: sound pressure changes the capacitance, and the front-end circuitry converts this change into an electrical signal. Depending on how the polarization field is provided, measurement microphones generally fall into two categories: externally polarized (polarization high voltage supplied by the measurement system, typically 200 V) and prepolarized (an internal electret provides the equivalent polarization, so no external high voltage is needed). Both can deliver high-precision measurements; the key to selection is system compatibility, environmental constraints, and maintenance cost. This article first explains how prepolarized and externally polarized microphones work and differ. It then compares power/front-end compatibility, noise and dynamic range, environmental robustness, and long-term stability. Next, it gives selection tips by scenario (metrology, approval tests, field, multichannel). It ends with a quick decision checklist. System Requirements Externally Polarized An externally polarized microphone requires a dedicated polarization unit / microphone power supply (provides 200 V polarization) to provide a stable polarization voltage (commonly 200 V) and to match the preamplifier interface (often 7-pin LEMO).This signal chain is closer to traditional metrology setups and is commonly used in laboratories and traceable calibration scenarios. Figure 1. Externally Polarized Microphone Structure Diagram Figure 2. Externally Polarized Microphone Set Prepolarized A prepolarized microphone uses an internal electret to provide equivalent polarization, so no external polarization voltage is required.System integration is simpler, making it well-suited for field work, mobile testing, and multi-channel distributed deployments. IEPE interfaces are widely used and broadly compatible; many data acquisition devices provide built-in IEPE inputs, which can significantly reduce overall equipment cost. (IEPE is the international term; some companies also refer to it as CCP or ICP.) Figure 3. Prepolarized Microphone Structure Diagram Figure 4. Prepolarized Microphone Set Engineering Trade-offs From an engineering application perspective, the main differences are: System compatibility: Externally polarized microphones depend on 200 V polarization and specific front-end/interfaces; prepolarized microphones place fewer requirements on the front-end and enable more flexible integration. Environmental robustness: High humidity, condensation, dust, oil mist, and similar environments can amplify insulation and leakage issues; prepolarized microphones often achieve more stable results. For high-temperature applications, carefully verify the model’s temperature limit and long-term drift data; externally polarized microphones are more commonly used where high-temperature stability and metrology-grade requirements are prioritized. Deployment and maintenance: Prepolarized solutions avoid high-voltage risk, deploy faster, and typically cost less at scale. Externally polarized setups demand higher standards for cleanliness, insulation, connector reliability, and troubleshooting capability. Selection Guidelines Front-End and Power Architecture If your existing front-end natively supports 200 V polarization and you have long used that metrology signal chain, prioritize externally polarized microphones to minimize retrofit effort and compatibility risk. If your front-end does not support polarization high voltage, or your system is mainly based on constant-current powering (e.g., CCLD/IEPE), prioritize prepolarized microphones for higher deployment efficiency and broader compatibility. Environmental Constraints (Humidity / Contamination / Temperature) For high humidity, condensation, dust, or oil mist in the field: prioritize prepolarized microphones or models with protective designs, and pay close attention to connector and cable protection. For high temperature or thermal cycling: base the choice on datasheets and stability data. Both externally polarized and high-temperature prepolarized models may be suitable, but you must verify the temperature limit and drift specifications. Align the Key Performance Targets Low-noise measurement: focus on equivalent self-noise, front-end noise, cable length, and shielding/grounding strategy. High SPL / shock measurement: focus on maximum SPL, distortion, overload recovery, and front-end input headroom (capsule size selection is often more critical than polarization method). Consistency / traceability: focus on calibration system, long-term drift, temperature coefficient, and maintenance interval. Budget and Total Cost of Ownership If budget is tight, channel count is high, or you need rapid scaling: prioritize prepolarized microphones. Without external polarization high voltage, the measurement chain is simpler and total investment is usually lower. If an externally polarized chain is required: include the external polarization power supply/adapter as a mandatory budget item. In addition to the microphone and preamplifier, a stable 200 V polarization supply is required, and the polarization supply can be costly. For multi-channel deployments, total cost rises significantly with channel count. If the laboratory already has sufficient channels of external polarization supplies, the incremental cost can be much lower. Conclusion There is no absolute “better” option between prepolarized and externally polarized microphones. A more reliable engineering approach is to first define the measurement chain and environmental constraints, then finalize the model selection using key metrics such as noise, dynamic range, consistency, and traceability. You are welcome to learn more about microphone functions and hardware solutions on our website and use the “Get in touch” form to contact the CRYSOUND team.

This integrated single-station EoL test solution enables automotive HVAC air vent suppliers to perform NVH (noise/BSR), motor electrical testing, and vane presence detection in a single inspection step, helping to improve overall test efficiency and reduce labor dependency. System Block Diagram of the Automotive HVAC Air Vent Test Solution Modern automotive HVAC air vent assemblies increasingly integrate multiple drive motors, multi-row vanes (louvers), and smart features such as automatic airflow control and voice interaction. As a result, upstream process variation or assembly defects can translate directly into vehicle-level concerns—typically perceived as abnormal noise, buzz/squeak/rattle (BSR), airflow direction mismatch, or reduced airflow caused by missing/misassembled vanes. To reduce rework and prevent customer complaints, suppliers increasingly require 100% end-of-line (EoL) testing on the production line, covering NVH (noise/BSR), motor electrical testing, and vane presence detection. CRYSOUND Single-Station EoL Test Solution CRYSOUND’s automotive HVAC air vent EoL test solution enables customers to perform single-station, 100% testing of noise/BSR, motor electrical testing, and vane presence detection. The solution integrates CRYSOUND’s in-house hardware and software, CRY3203-S01 measurement microphone set, SonoDAQ, CRY7869 acoustic test box, and OpenTest. And it combines electroacoustic measurement with abnormal noise analysis (sound quality and AI-based algorithms) to identify noise/BSR issues that FFT and Leq may miss. It also integrates motor electrical testing and vane presence detection, enabling one-time clamping and a single OK/NG decision within the same sound-insulated EoL station. Schematic of the HVAC Air Vent Test Fixture Customer Results: Efficiency, Labor, and Quality Gains Replaced manual listening with machine-based detection, enabling unified criteria with quantitative, traceable results. One fixture, three test positions: supports parallel or mixed testing of left/center/right dashboard air vents, improving efficiency by >100%. Variant support via fixture changeover: reuse the same test station across different products, reducing repeated capital investment. One-operator, one-click inspection: a single line can save 1–2 long-term operators. EoL Test Equipment for Automotive HVAC Air Vent Typical Target Users This solution is designed for suppliers of motorized air vents and other motor-driven interior components,such as Valeo S.A.,Ningbo Joysonquin Automotive Systems Co., Ltd. and Jiangsu Xinquan Automotive Trim Co., Ltd. Main Hardware and Software Configuration ProductQty.NoteCRY3203-S01 Measurement Microphone Set1Measurement Microhone SetCRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro1Audio AnalyzerCRY7869 Acoustic Test Box1Test EnvironmentOpenTesthttp://www.opentest.com1SoftwareFixture1CustomizablePC & Monitor1(Optional) Feel free to fill in the form below ↓to contact us. Our team can share application-specific EoL testing recommendations based on your automotive HVAC air vent requirements.

In industrial production and environmental monitoring, excessive noise implies compliance risks or potential complaint disputes. To handle this, you need a professional sound level meter (SLM) that provides "credible, traceable, and analyzable data." Faced with price differences ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars, and a complex array of parameters, how do you choose without making costly mistakes? We have distilled the complex selection process into a "4-Step Decision Method" to help you quickly find the balance between your budget and your needs. Step 1: Define the "Purpose" — Does the data need to be externally accountable? This is the first watershed moment in selection, directly determining the equipment's "Accuracy Class." Scenario A: Data must be "Externally Accountable" Typical Use Cases: Environmental law enforcement, third-party testing, laboratory R&D, legal arbitration. Must Choose: Class 1 Sound Level Meter. Key Reason: The difference between Class 1 and Class 2 goes beyond reading errors. The core difference lies in the Frequency Response Range. Class 1 Devices (e.g., CRY2851): Typically cover a wide band of 10 Hz – 20 kHz, capturing extremely low-frequency vibrations and ultra-high-frequency noise, fully meeting strict standards like IEC 61672-1:2013 Class 1. Class 2 Devices: Usually have a narrower frequency range (e.g., 20 Hz – 8 kHz) with potential attenuation at high or low ends, making them unsuitable for strict metering or certification scenarios. Scenario B: Used only for "Internal Management" Typical Use Cases: Workshop inspections, equipment spot checks, community surveys, internal process comparisons. Recommended: Class 2 Sound Level Meter. Core Advantage: It meets the vast majority of industrial and environmental noise measurement needs and is the ideal choice for internal control. Step 2: Clarify "Indicators" — What exactly are you measuring? Selecting the wrong indicators renders the data useless. Focus on the following two points: Frequency Weighting (A, C, Z): Which one to use? A-Weighting (Most Common): Simulates the human ear's response (insensitive to low frequencies). Must be used for Environmental Noise Evaluation and Occupational Health Assessments (e.g., 85 dB(A) limits). C-Weighting: Less attenuation at low frequencies, reflecting the total energy of the sound more truly. Often used for Mechanical Noise and Impact Sound where rich low-frequency components exist. Z-Weighting (Zero Weighting): Flat response across the entire frequency range with no attenuation. Must be used when you need Spectrum Analysis or deep research into noise components to preserve the original signal. "Instantaneous Value" or "Statistical Value"? For quick site checks: Focus on Lp (Instantaneous Sound Pressure Level) and Lmax (Maximum Sound Level). For scientific assessment or reporting: You must have Leq (Equivalent Continuous Sound Level). This is the core metric for evaluating noise energy over a period of time. Professional equipment (like CRY2850/2851) comes standard with integrating functions to automatically calculate Leq. Figure 1. Software Interface Diagram Step 3: Confirm if "Analysis" is needed — Do you need to find the noise source? This distinguishes a "regular noise meter" from a "professional sound level meter." Looking at a total value (e.g., 85dB) only tells you "it's noisy here"; seeing the spectrum tells you "where is it noisy." When do you need Spectrum Analysis (1/1 Octave, 1/3 Octave, or FFT)? Noise Control: Determining if noise comes from a fan (aerodynamic noise) or a motor (electromagnetic noise). R&D: Comparing sound quality differences between competing products or iterations. Diagnostics: Distinguishing between high-frequency bearing squeal and low-frequency structural resonance. Selection Advice: Taking the CRY2851 as an example, it supports both OCT Analysis and FFT Analysis. If your goal is to "solve problems" rather than just "record numbers," be sure to choose a device with spectrum functions. Figure 2. Measurement Demonstration Step 4: Plan the Measurement "Mode" — Single measurement or long-term monitoring? Many projects fail because the device "measures accurately, but is hard to use." Dynamic Range: Say goodbye to "Manual Gear Shifting" Old equipment requires manual range switching, which is prone to errors. Modern sound level meters (like CRY2851) feature a >120 dB wide dynamic range, covering everything from whispers to roaring engines without switching gears—preventing errors and improving efficiency. Data Export: Ensure data is "Portable and Usable" Ensure the device supports automatic storage to an SD card or internal memory and exports in universal formats (like CSV). Avoid the trap of "measuring data but failing to record it manually." Remote Monitoring Capability (Essential for Outdoor/Long-term) For long-term scenarios like construction sites or traffic monitoring, the device must have: Communication Functions: (LAN/Serial Port) for real-time remote data transmission. Outdoor Protection: (e.g., paired with NA41 Outdoor Kit, IP65 rating) to withstand rain and dust; otherwise, the equipment is easily damaged. Quick Selection Cheat Sheet To help you decide quickly, we have summarized three typical application scenarios based on the four-step method above: Figure 3. Handheld Measurement Operation The "Avoid Pitfalls" Checklist: Check these 5 points last Check the Standard: Confirm compliance with the latest IEC 61672-1:2013 standard. Check Bandwidth: Even for Class 2 meters, ensure the frequency range covers your main noise sources to avoid missed detections. Check Calibration: Buying a Class 1 SLM requires a Class 1 Sound Calibrator (e.g., CRY563A); otherwise, the system accuracy is downgraded. Check Range: Prefer "Wide Dynamic Range" or "Auto-Range" devices; refuse manual gear shifting. Check Accessories: Windscreens and protective cases are mandatory for outdoor use. Selecting a sound level meter is essentially balancing "Risk vs. Cost." If you still have doubts about "Class 1 vs. Class 2" or "Whether Spectrum Analysis is needed," CRYSOUND is ready to provide full lifecycle support: Pre-sales: Our application engineers provide one-on-one scenario consulting to help you match precisely and avoid wasting money. After-sales: We offer a full suite of services from calibration and training to long-term technical support, ensuring a complete chain of evidence. Instead of struggling with parameters alone, get in touch with our team using the form below to receive a configuration plan tailored to your application.

This article is for engineers working in acoustics and vibration testing. It introduces how to perform sound quality measurements in OpenTest based on the ISO 532 loudness standard and the ECMA-74 tonality evaluation methods. By measuring and comparing three key psychoacoustic metrics — Loudness, Sharpness, and Prominence (Tonality) — teams in consumer electronics, automotive NVH, home appliances and IT equipment can turn “how good or bad it sounds” into quantitative engineering data, and complete a standardized sound quality workflow on a single platform from data acquisition, through analysis, to reporting. Why Sound Quality Measurements Matter In traditional noise testing, we usually rely on dB values to describe how “loud” a device is. But more and more studies and real-world projects are reminding engineers that “loudness” is only part of the story. In automotive NVH, home appliances, IT equipment and consumer electronics, user acceptance of product sound depends much more on whether it sounds pleasant, sharp, tiring or annoying, not just the overall sound pressure level. Industry surveys also show that most manufacturers now treat “how good it sounds” as being just as important as “how quiet it is”, and they start paying attention to sound quality already in early design phases. At the same sound level, poor sound quality can significantly drag down overall product satisfaction. This is exactly why Sound Quality as a discipline exists: through a set of psychoacoustic metrics such as Loudness, Sharpness and Tonality/Prominence, it turns subjective impressions like “sharp”, “boomy”, “harsh” or “smooth” into data that is measurable, comparable and traceable, so engineering teams can go beyond noise control and truly design and optimize product sound around listening experience. Key Metrics in Sound Quality Measurement In engineering practice, sound quality is not a single number, but a set of psychoacoustic quantities. Commonly used metrics include Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Fluctuation Strength, Prominence/Tonality, etc. Figure 1 – Key metrics in sound quality measurement Loudness (ISO 532-1) Loudness and Loudness Level describe how loud a sound is perceived by the human ear, rather than just its sound pressure level in dB. Internationally, the ISO 532-1:2017 standard based on the Zwicker method is widely used for loudness calculation. It can handle both stationary and time-varying sounds and correlates well with subjective perception in many technical noise applications. From an engineering point of view, loudness has clear advantages over A-weighted SPL: It accounts for the ear’s different sensitivity to frequency (human hearing is more sensitive in the mid-high range) At the same dB level, loudness often tracks “does it feel loud or not?” more accurately Sharpness (DIN 45692) Sharpness reflects whether a sound is perceived as sharp or piercing. When the high-frequency content has a higher proportion, people tend to feel the sound is more “sharp” or “edgy”. Sharpness was standardized in DIN 45692:2009, and is typically calculated based on the specific loudness distribution from a loudness model, applying additional weighting in the higher Bark bands. The result is expressed in acum. In applications such as fans, compressors and e-drive whine, reducing sharpness often improves subjective comfort more effectively than just lowering the overall dB level. Roughness (asper) Roughness corresponds roughly to fast amplitude modulation in the 15–300 Hz range, which gives a “raspy, vibrating” impression — for example in certain inverter whines or gear whine where the sound feels like it is “shaking”. Unit: asper Classical definition: 1 asper corresponds to a 1 kHz, 60 dB pure tone amplitude-modulated at about 70 Hz with 100% modulation depth The deeper the modulation and the closer the modulation frequency is to the sensitive region (around 70 Hz), the higher the perceived roughness In engineering, roughness is often used to describe how much a sound feels like it is “buzzing” or “scratching”, and it is particularly relevant for subjective evaluation of technical noise in e-drive systems, gearboxes and compressors. Fluctuation Strength (vacil) Fluctuation Strength captures slower amplitude fluctuations — amplitudes that go up and down in the range of roughly 0.5–20 Hz, perceived as “pulsing” or “breathing”, with a typical peak sensitivity around 4 Hz. Unit: vacil A classical definition of 1 vacil: a 1 kHz, 60 dB pure tone with 4 Hz, 100% amplitude modulation In cabin idle “breathing noise”, or fans whose level periodically rises and falls, fluctuation strength is a key descriptor You can think of Fluctuation Strength and Roughness as two sides of the same “modulation” coin: Fluctuation Strength: slow modulation (a few Hz), perceived as “breathing” or “pulsing” Roughness: faster modulation (tens of Hz), perceived as “vibrating, raspy, grainy” Prominence / Tonality (ECMA-74) Many devices are not particularly loud overall, yet become extremely annoying because of one or two narrowband tonal components. These “sticking out tones” are usually quantified by Tonality / Prominence. In IT and information technology equipment noise, ECMA-74 specifies methods based on Tone-to-Noise Ratio (TNR) and Prominence Ratio (PR) to evaluate tonal prominence and to determine whether a spectral line is a “prominent tone”. Historically, these metrics come from psychoacoustic research and are now widely used in automotive, aerospace, home appliances and IT equipment to predict and optimize annoyance. For example, studies have shown that, with loudness controlled, Sharpness, Tonality and Fluctuation Strength are important predictors for the annoyance of helicopter noise. Why Sound Quality Is More Useful Than Just “Watching dB” In many projects, you may have already seen questions like these: Two fan designs have similar sound power levels, but one “sounds smooth” while the other has a clear whine After noise reduction, overall SPL is a few dB lower, but user feedback hardly improves On the production line, A-weighted SPL is used as the only criterion, and some “bad-sounding” units still slip through Fundamentally, that is because: Sound pressure level / sound power = “how much energy is there” Sound quality metrics = “how the ear feels about it” With metrics like Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Fluctuation Strength and Prominence, you can decompose vague complaints like “it just sounds uncomfortable” into: Which frequency region has too much energy (leading to high sharpness) Whether there is strong amplitude modulation (causing high roughness or fluctuation strength) Whether any tonal component is sticking out clearly above its surroundings (high tonality / prominence) In engineering iteration, these metrics can be mapped directly to: Structural optimization (stiffness, modes, blade shape, etc.) Control strategies (e.g. PWM frequency, fan speed curves and transitions) Material and noise treatment / isolation choices This gives you much clearer and more actionable directions than “just reduce dB”. Sound Quality Analysis in OpenTest As a platform for acoustics and vibration testing, OpenTest supports a complete sound quality workflow from acquisition → analysis → reporting. Fill in the form at the bottom ↓ of this page to contact us and get an OpenTest demo. Example Device: Office PC Fan Noise To make the process concrete, we use a very accessible device as our example: a typical office PC. Test objective: evaluate sound quality metrics of its fan noise under different operating conditions, in order to: Compare subjective noise performance of different cooling and fan control strategies Provide quantitative input to NVH reviews (e.g. does loudness exceed the target, is sharpness too high?) Build a foundation for further sound quality optimization (e.g. suppressing whine frequencies, smoothing speed transitions) Test environments might be: A semi-anechoic room / low-noise lab (recommended); or A quiet office environment for early-stage, comparative evaluation Measurement System: SonoDAQ + OpenTest Sound Quality Module On the hardware side, we use a CRYSOUND SonoDAQ multi-channel data acquisition system (for more detailed model information, please contact us), together with one or more measurement microphones placed near the PC fan or at the listening position, according to the test requirements. Figure 2 – SonoDAQ Pro multi-channel data acquisition system Of course, OpenTest also supports connection via openDAQ, ASIO, WASAPI and other mainstream audio interfaces, so you can reuse existing DAQ devices or audio interfaces for measurement where appropriate. On the software side, the Sound Quality module in OpenTest is one of the measurement modules. Combined with FFT analysis, octave analysis and sound level analysis, it can cover most standard audio and vibration test needs. Configuring Measurement Parameters After creating a new project in OpenTest, proceed as follows: 1. Channel configuration and calibration In Channel Setup, select the microphone channels to be used and set sensitivity, sampling rate and frequency weighting as required Use a sound calibrator (e.g. 1 kHz, 94 dB SPL) to calibrate the measurement microphones, ensuring that loudness and related metrics have a reliable absolute reference 2. Switch to the “Measure > Sound Quality” module Select the metrics to be calculated: Loudness, Sharpness, Prominence Set analysis bandwidth, frequency resolution and time averaging modes Optionally configure test duration and labels for different operating conditions Essentially, this step turns the “calculation definitions” in ISO 532, DIN 45692 and ECMA-74 into a reusable OpenTest sound quality scenario template. Acquiring Sound Data for Different Operating Conditions Once the test environment is set up and the parameters are configured, click Start to measure sound quality data under different operating conditions. Each test record is saved automatically for later analysis. Because sound quality focuses on how it sounds during real use, it is recommended to record several typical conditions, for example: Idle / standby (fan off or low speed) Typical office load (documents, multi-tab browsing, etc.) High load / stress test (CPU/GPU at full load) With this breakdown, engineers can clearly manage which sound quality result corresponds to which operating condition. Figure 3 – Overlaying multiple sound quality test records in OpenTest From Multiple Measurements to One Sound Quality Report After measuring multiple operating conditions (e.g. idle, typical office and full-load stress test), you can do the following in OpenTest. In the data set list, select the records you want to compare and overlay: Compare loudness curves under different conditions See whether sharpness spikes during acceleration or speed transitions Identify conditions where prominent narrowband tones appear (high prominence) In the Data Selector, save the associated waveforms and analysis results: Export .wav files for later listening tests or subjective evaluations Export .csv / Excel for further statistics or modelling Click the Report button in the toolbar: Enter project, DUT and operating condition information Select sound quality metrics and plots to include (e.g. loudness vs. time, bar charts of sharpness, spectra with marked tonal prominence) Generate a sound quality report with one click for internal review or customer submission Figure 4 – Example of a sound quality report in OpenTest The generated report includes measurement conditions and operating modes, key sound quality metrics such as Loudness, Sharpness and Prominence, as well as a comparison with traditional acoustic metrics (sound pressure level, 1/3-octave spectra, sound power, etc.), making it easier for project teams to discuss using a set of metrics that are both objective and closely related to perceived sound. Typical Application Scenarios You can build different sound quality test scenarios in OpenTest for different businesses, for example: Consumer electronics / IT equipment (laptops, routers, fans, etc.) Use loudness + sharpness + (where applicable) roughness to evaluate the “subjective comfort” of different thermal / fan strategies Compare sound quality across different speed curves or PWM schemes Automotive NVH / e-drive systems Use multi-channel acquisition to record interior noise and speed signals synchronously Combine order analysis with sound quality metrics to see how “sharp” an e-drive whine is and whether there is pronounced modulation causing roughness Home appliances and industrial equipment When sound power already meets standards, use sound quality metrics to further screen for “annoying noise”, instead of relying only on dB If you are building or upgrading your sound quality testing capabilities, you can use ISO 532 and ECMA-74 as the backbone and let OpenTest connect environment, acquisition, analysis and reporting into a repeatable chain. That way, each sound quality test is clearly traceable and much more likely to evolve from a single experiment into a long-term engineering asset. Welcome to fill in the form below ↓ to contact us and book a demo and trial of the OpenTest Sound Quality module. You can also visit the OpenTest website at www.opentest.com to learn more about its features and application cases.

Measurement microphones are used in acoustic metrology, type-approval testing, and engineering measurements. Unlike general audio capture applications, measurement scenarios place far greater emphasis on consistency and traceability: the same microphone should deliver stable output when re-tested over time; variation within a production lot should be sufficiently small; and performance fluctuations between lots should remain controllable. In these applications, tiny contaminants introduced during manufacturing may not cause immediate “failure,” but can accumulate over time as increased self-noise, subtle shifts in frequency response, changes in insulation leakage, or long-term drift—ultimately increasing measurement uncertainty and recalibration costs. Therefore, completing critical component assembly and sealing steps inside a controlled clean environment (a cleanroom) is a common engineering approach to achieve stable performance and batch-to-batch consistency for measurement-grade microphones. This article starts with measurement microphone structures and traceability requirements, then explains how particulate and molecular contamination affects noise, response, and drift. It next outlines cleanroom controls (cleanliness class, environment, people/material flow) that reduce risk. Finally, it summarizes benefits for consistency and recalibration cost. Figure 1. Precision Assembly in a Cleanroom Critical Structure and Measurement-Grade Requirements Taking a condenser measurement microphone as an example, its core structure consists of the diaphragm, backplate, an extremely small gap, and acoustic pathways. The dimensions and surface conditions of these structures directly affect sensitivity, frequency response, phase characteristics, and self-noise. Measurement microphones typically need to meet standardized geometric and electroacoustic requirements and support a traceable calibration chain. For example, the IEC 61094 series specifies requirements related to measurement microphone specifications and calibration, helping ensure comparability and consistency when used as metrology instruments and transfer standards. How Contamination Affects Performance Contamination typically falls into two categories: particulate contamination (dust, fibers, skin flakes, metal debris, etc.) and molecular contamination (oil mist, residual volatile organic compounds, cleaning-agent residues, etc.). For measurement microphones, both can alter boundary conditions of diaphragm motion, acoustic damping, or electrical insulation. Particulate Contamination: Self-Noise, Nonlinearity, and Response Deviation When particles enter critical gaps or adhere near the diaphragm, they may introduce localized friction and changes in damping, raising self-noise and reducing the effective dynamic range for low-level measurements. In more extreme cases, particles can cause intermittent contact or restricted motion, resulting in nonlinear distortion and poorer repeatability. Figure 2. Microphone Cross-sectional Structure Molecular Contamination: Changes in Insulation and Charge Stability Molecular contamination often appears as thin-film deposits on surfaces. Such films may change surface resistance on insulating parts, altering leakage currents and therefore affecting effective polarization conditions and low-frequency stability, potentially increasing electrical noise. For measurement chains requiring long-term stability, issues caused by molecular contamination are more subtle and often manifest as slow drift. Moisture Absorption/Migration and Batch Variation: Long-Term Stability and Consistency Some contaminants are hygroscopic or migratory. Under temperature and humidity cycling and long-term aging, their distribution and surface state may keep changing, causing gradual drift in sensitivity and frequency response. Meanwhile, contamination events are inherently random: the location and amount of particle deposition are hard to reproduce, which can amplify within-lot dispersion and lead to yield fluctuations—ultimately increasing the workload for system-level calibration and consistency control. The Engineering Value of a Cleanroom: Bringing “Contamination Risk” Under Process Control A cleanroom keeps particulate and molecular contamination within a verifiable range and stabilizes environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and pressure differential. Cleanroom classification commonly references ISO 14644-1, which uses airborne particle concentration as the primary metric. For measurement microphones, the key is to bring contamination risk in assembly, sealing, and packaging steps under process control. Completing critical assembly and sealing in a low-particle environment reduces the likelihood of random dust and fiber contamination. Controlling temperature/humidity, pressure differential, and implementing electrostatic management reduces risks from adsorption and secondary deposition. Following standardized protocols for personnel/material entry and tool maintenance—and maintaining clean packaging—helps preserve a consistent “as-shipped” condition. At CRYSOUND, critical assembly and sealing are performed in a Class 1,000 cleanroom, equivalent to ISO Class 6 under ISO 14644-1. It helps reduce particulate contamination risk during mass production while keeping process conditions stable. Figure 3. Cleanroom Manufacturing Area Cleanrooms and Calibration: Complementary, Not a Substitute A cleanroom controls contamination variables during manufacturing to reduce the risks of performance dispersion and drift. Calibration establishes traceability and provides parameters such as sensitivity under specified conditions. Clean manufacturing cannot replace calibration, but it can improve re-test consistency and reduce the impact of drift on calibration intervals and uncertainty. Figure 4. Cleanroom Manufacturing Direct Value for End Applications Once contamination variables are controlled, self-noise levels and response characteristics become more stable, and batch-to-batch differences are easier to manage. In multi-channel systems, acoustic imaging measurements, and production-line consistency monitoring, sensor interchangeability is easier to achieve—and it also becomes easier to define more appropriate recalibration and periodic verification strategies. A clean, controlled environment provides stable contamination control conditions for key manufacturing steps of measurement microphones, helping reduce risks of elevated self-noise, response deviation, and long-term drift. Combined with standardized design, in-process inspection, and traceable calibration, reliable measurement results can be maintained throughout the product lifecycle. You are welcome to learn more about microphone functions and hardware solutions on our website and use the“Get in touch”form to contact the CRYSOUND team.

Before you begin any formal data acquisition work, one critical step is connecting the DAQ front end to the PC. In day‑to‑day engineering, the most common options include USB direct connection, Wi‑Fi wireless, Ethernet, and PXIe. This article introduces these four common connection methods from several angles—how they differ, where each one shines, and their practical limitations—to help you build a deeper, more intuitive understanding of DAQ connectivity. Ethernet Connection An Ethernet connection means the front end joins a local area network (LAN) through its network port, and the PC accesses the device over IP. A typical data path looks like this: Sensor → front‑end sampling → Ethernet transport (TCP/UDP, etc.) → PC/server storage and processing. This topology ranges from very simple to quite complex, for example: Front end ↔ PC (point‑to‑point direct link) Multiple front ends → switch → PC/server (distributed) Figure 1. Ethernet Connection Advantages of Ethernet Connections Flexible topology: single‑node, multi‑node, and distributed setups are all easy to organize; Comfortable distance and cabling: copper Ethernet or fiber makes it easier to deploy across rooms, floors, or even buildings—and routing can be more standardized; Mature infrastructure and strong maintainability: switches, cables, transceivers, fiber, and rack accessories are widely available, and issues are usually easier to locate and troubleshoot; Limitations of Ethernet Connections The network introduces uncertainty—topology, switch performance, port congestion, broadcast storms, and link errors can all cause throughput/latency fluctuations; With multiple devices/nodes, the need for network planning rises quickly: IP addressing, subnetting, whether to use DHCP, routing across subnets, switch cascade depth, etc. As the system grows, things can get messy without a plan. Cable quality, shielding/grounding, routing close to high‑power lines, poor port contact, or switch power instability may show up as packet loss, retransmissions, or speed‑negotiation anomalies. For engineers, Ethernet is straightforward on the test floor: in many setups, a single cable is enough to bring the DAQ front end online with the PC—parameter setup, start/stop, live monitoring, and logging all feel smooth. When the distance grows, you can extend the copper run or switch to fiber to keep transmission stable. In cross‑floor or multi‑room environments—or where noise/safety constraints make it inconvenient to stay near the rig—data can be acquired and monitored from an office or control room over the network. Of course, very long cable runs can be a headache in their own right. SonoDAQ Pro comes standard with two Gigabit LAN ports (GLAN, daisy‑chain capable, supporting 90 W PoE++ power delivery) and also provides a USB‑C port with gigabit‑class throughput, giving users more flexible network‑style connection options. Figure 2. SonoDAQ Rear Panel Wi‑Fi Connection Wi‑Fi DAQ means the acquisition node communicates with a PC or a LAN over a wireless network. Unlike simply “replacing the cable with wireless,” Wi‑Fi DAQ systems typically have two working modes: Real‑time streaming: after sampling, data is sent to the PC over Wi‑Fi in real time; Local buffering/storage: data is first buffered or stored on the front end; Wi‑Fi is used mainly for control, preview, transferring selected segments, or exporting after the run. Two common networking setups are: The DAQ front end joins an on‑site access point (STA mode); The PC creates a hotspot and the DAQ front end connects to it. In short, the front end must support Wi‑Fi, and it must be on the same LAN as the PC. Figure 3. Wi-Fi Connection Advantages of Wi‑Fi Connections No cabling: when wiring is difficult or not allowed, the DAQ can be placed close to the measurement point and controlled over Wi‑Fi; Flexible remote acquisition: by mapping the DAQ’s IP to the public Internet, the PC can access the DAQ by IP address for ultra‑long‑distance remote control. Limitations of Wi‑Fi Connections Uncertainty for sustained high‑volume transfers: available wireless bandwidth can change at any time, so long, continuous acquisitions are more likely to expose packet loss/retransmissions/buffer overflows—the heavier the data load, the more obvious this becomes; Stability depends heavily on the environment: multipath, co‑channel interference, AP congestion, and movement (changing the RF path) can all cause throughput swings and higher latency/jitter, showing up as choppy live plots or occasional disconnect/reconnect events. In real projects, Wi‑Fi is most often used when cabling is inconvenient or prohibited, or when remote/off‑site acquisition is required but running Ethernet is impractical. Engineers can configure parameters remotely, start/stop acquisition, monitor key metrics, or pull specific segments. For larger datasets or long‑duration logging, it’s common to pair Wi‑Fi with front‑end buffering/local storage—Wi‑Fi keeps things visible and controllable, while the front end protects data integrity. USB Connection A USB DAQ device typically means sampling happens in an external front end (with built‑in ADCs, signal conditioning, clocks, etc.). The PC handles configuration, visualization/analysis, and data storage, while USB “moves” the data into the computer. In this relationship, the PC acts as the USB host and the front end acts as the USB device. Figure 4. USB Connection Advantages of USB Connections Low barrier and quick to start: no IP setup and no dependency on network infrastructure—plug it in, install the driver/software, and you can usually start acquiring; Highly portable: an external box plus a laptop is a common combo, well suited to field work, customer sites, and temporary setups; Ubiquitous interface: cables, adapters, mounting clips, and docks are easy to source; Limitations of USB Connections Scalability is generally less “natural” than network/platform approaches. When a system grows from a single front end to multiple front ends and coordinated multi‑point measurements, cabling, device management, and synchronization depend more on the specific implementation; If multiple high‑throughput devices share the same USB controller (DAQ front end, external SSD, camera, etc.), you may see throughput fluctuations, buffer warnings, and occasional stuttering. USB controllers, driver stacks, system load, and power‑management policies vary from PC to PC, so the same device can behave differently on different hosts. Most USB front ends are portable external devices. They often integrate a reasonably complete set of general‑purpose measurement interfaces—analog inputs/outputs, digital I/O, counters/encoders, etc. With a single USB cable, you get both connection and control to the PC for acquisition, display, and storage. As a result, USB is widely used for temporary measurements in the field or at customer sites, rapid R&D bring‑up and debugging, and small‑channel, short‑duration tests. PXIe Interface PXIe is a platform form factor built around a chassis, backplane, and modules. Measurement/instrument modules plug into the chassis and interconnect through the backplane; the chassis then works with a controller or an external link to a PC workstation. Compared with a single external DAQ box, PXIe is more platform‑oriented, modular, and capable of system‑level composition. If a PXIe controller is installed in the chassis, the chassis effectively becomes the host and can run acquisitions independently. Without a PXIe controller, a PXIe chassis is typically not connected to a PC via a standard Ethernet port. Instead, it uses a remote‑control link that essentially “extends the PCIe bus” so an external PC can see the chassis modules as if they were local PCIe devices. In practice, the two most common options are MXI‑Express (a host interface card in the PC plus a remote‑control module in the chassis, linked with a dedicated cable) and Thunderbolt. A typical data path looks like this: Sensor → PXIe module sampling/processing → chassis backplane → controller/link → PC/storage Figure 5. PXIe interface Advantages of PXIe Interface You can populate the chassis with the functional modules you need (analog, digital, bus interfaces, switch matrices, etc.). System capability comes from the “module mix,” and adding or swapping modules later is straightforward; High level of engineering integration: power, cooling, and mechanical form factor feel more like a test platform. In rack/bench systems, cabling, maintenance, and spare‑parts management are easier to standardize; When a test system is expected to evolve—more channels, more functions, module upgrades over time—the platform’s long‑term scalability is a strong advantage. Limitations of PXIe Interface Higher cost and larger footprint: a chassis + module ecosystem is typically a bigger investment than “PC + single card/box,” and it tends to be a fixed installation. Less friendly for mobile/field work: for scenarios that require frequent transport and rapid setup, PXIe’s platform advantages can become a burden; Higher system‑build complexity: it’s more like building a test system, where rack layout, harness management, thermal design, power headroom, and grounding all need to be considered. In practice, SonoDAQ Pro adopts a PCIe‑based modular backplane architecture. Each functional module connects to the main control platform (ARM) through the backplane for high‑speed data uplink/downlink, synchronization, and power distribution. We call this internal interconnect “Trilink.” While enabling modular expansion, SonoDAQ Pro also supports external communication interfaces such as GLAN, Wi‑Fi, and USB‑C, significantly improving deployment flexibility. For a more hands‑on view of how SonoDAQ works over different connection methods (USB / Wi‑Fi / GLAN)—including real usage workflows, representative scenarios, and common configuration checklists—please fill out the Get in touch form below and we’ll reach out shortly.

CRY580 A²B Interface is a bidirectional bridge designed to connect the A²B (Automotive Audio Bus) ecosystem with standard test & measurement setups (e.g., SonoDAQ, CRY6151B, Audio Precision). This article explains what makes A²B testing challenging—most analyzers don’t have a native A²B interface—and how CRY580 solves it by encoding/decoding A²B streams and converting them into measurable Analog or S/PDIF outputs, while supporting multi-channel I²S/TDM audio paths for fast, repeatable validation. Faster Automotive Audio Testing with CRY580 One bidirectional A²B bridge for testing: apply an analog/digital test stimulus for A²B amplifier testing, and bring A²B microphone or accelerometer sensor streams out as analog or S/PDIF for measurement. The A²B Audio Bus Is Reshaping In-Vehicle Audio A²B technology enables cost-effective audio data transport over long distances, combining multichannel audio (I²S/TDM), control (I²C), and power delivery over affordable cabling. Bidirectional data transfer at 50 Mbps bandwidth Low and deterministic latency(50 µs) System-level diagnostics Slave nodes can be locally-powered or bus-powered Programmable using ADI's SigmaStudio® GUI Uses cost-effective cables(unshielded twisted pair) The Testing Pain: A²B Adds Performance—And Complexity Traditional audio analyzers do not include A²B interfaces, making it impossible to directly test A²B devices. To perform accurate testing, a dedicated A²B codec is required to decode and convert A²B audio signals into standard analog or digital formats for measurement and analysis. How Bridging to Measurements Works in Practice How A²B Technology and Digital Microphones Enable Superior Performance in Emerging Automotive Applications A²B Microphone A²B Accelerometer A²B Amplifier "Bridging" in practice means converting A²B audio signals into standard analog or digital formats for testing: for A²B amplifier testing, injecting analog/digital stimulus into the A²B bus; and for A²B sensor testing, extracting A²B audio data to analog or S/PDIF for measurement. The CRY580 serves as the ideal bidirectional test bridge, facilitating seamless conversion and measurement in both directions. Introducing CRY580: An A²B Interface Built for Automotive Testing The CRY580 is a versatile A²B interface designed to seamlessly bridge A²B networks with testing equipment. It provides both decoding and encoding capabilities, allowing for the efficient transfer of audio data between A²B devices and standard measurement systems. Whether you're testing A²B microphones, amplifiers, or sensors, the CRY580 enables smooth and reliable testing workflows, ensuring accurate results across a range of automotive audio applications. CRY580 A²B Interface Who Buys CRY580 and What They Test OEM / Tier1 Audio Teams: Integration, debugging, and acceptance testing across A²B networks. A²B Microphone & Mic-Array Suppliers: Sensitivity, frequency response (FR), and phase consistency checks. A²B Amplifier / Audio Processor Suppliers: Amplifier testing with injected stimuli, as well as mapping and performance verification. Test Labs: Standardized A²B measurement processes and delivery. Manufacturing / EOL QC: Repeatable pass/fail testing with faster fault isolation. Typical Test Setups: More Than Just an Interface At CRYSOUND, we provide more than just the CRY580 A²B interface. We offer a full automotive audio testing solution, including audio acquisition cards, microphones and sensors, acoustic sources, custom fixtures, acoustic test boxes, and vibration shakers, delivering a complete and streamlined testing experience. Here’s a description of the testing block diagram, including the use of the latest OpenTest Audio Test & Measurement Software https://opentest.com The CRY580 A²B Interface can be used in conjunction with the Audio Precision. Digital Interface Analog Interface "Performing A²B microphone performance tests (Frequency Response, THD+N, Phase, SNR, AOP) in an anechoic chamber, using the CRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro, CRY580 A²B Interface, and other equipment.” Why CRYSOUND: A Complete Automotive Audio Test Ecosystem The value of end-to-end delivery: reducing system integration time and minimizing coordination costs between multiple suppliers. We cover everything from R&D to production line testing. BOM list of the solution CRY580 bridges A²B to mainstream test & measurement setups in both directions, turning complex in-vehicle audio validation into a faster, repeatable workflow from R&D to end-of-line production. To discuss your use case, system configuration, or a demo, please fill out the Get in touch form below and we’ll reach out shortly.

In audio and vibration testing, FFT analysis (Fast Fourier Transform) is one of the tools almost every engineer uses sooner or later: Loudspeaker frequency response Headphone distortion NVH diagnostics Structural resonance troubleshooting Production noise and “mysterious tone” hunting A lot of practical questions are actually asking the same few things: Where is the energy concentrated in frequency? Is it dominated by one tone or a bunch of harmonics? How high is the noise floor? Are there any resonance peaks? FFT is the most universal entry point to answer these questions. This article will help you clarify three things from an engineering perspective: What FFT analysis is How FFT works conceptually How to use FFT correctly and efficiently in practice What Is FFT? In the time domain, a signal is just a waveform changing over time – all components “stacked together” in one trace. You can see it, but it’s hard to tell which frequencies are inside. FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) decomposes a time-domain signal into a sum of sinusoids at different frequencies. In the frequency domain, the signal is represented by frequency + amplitude + phase. In simple terms: Time domain: how the signal moves over time Frequency domain: what frequency components it contains, which are strongest, and how they relate to each other Historically, Fourier’s key idea (early 19th century) was that a complex periodic function can be expressed as a sum of sines and cosines. This evolved into the continuous-time Fourier transform, mapping signals onto a continuous frequency axis. In the computer age, things changed: engineers work with sampled data and typically only have a finite-length record of N samples. That leads to the DFT (Discrete Fourier Transform), which maps N time samples to N discrete frequency bins. FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) is not a different transform. It is a family of algorithms that compute the exact same DFT much more efficiently: Direct DFT: complexity ~ O(N²) FFT: complexity ~ O(N log N) The output X[k] is identical to the DFT result – FFT just gets there far faster by exploiting symmetry and divide-and-conquer. What FFT Is Good at – and What It Isn’t FFT is very good at: Finding deterministic narrowband components Fundamental tones, harmonics, switching frequencies, whistle tones, speed-related lines Looking at broadband distributions Noise floor, 1/f slopes, in-band power, SNR Characterizing system behavior Transfer functions, resonances / anti-resonances, coherence, delay estimation Serving as the foundation of time–frequency analysis STFT, spectrograms, etc. FFT is not good at (or not sufficient on its own for): Strongly non-stationary signals and “instantaneous frequency” For chirps and rapidly changing content, you need STFT, wavelets, or other time–frequency methods, not a single FFT on a long record Separating two extremely close tones below your frequency resolution If the spacing is smaller than your bin resolution (set by N), no algorithm will magically resolve them Turning short data into “long measurements” Zero padding only interpolates the spectrum visually; it does not add new information Before Using FFT: Key Concepts to Get Right To use FFT well, you need to be confident about a few fundamentals: Sampling rate DFT and its interpretation What you actually plot (magnitude, amplitude, power, PSD) Windowing and spectral leakage Averaging Sampling Rate: How High in Frequency You Can See Before FFT, you already made one crucial decision: sampling. A continuous-time signal x(t) is turned into a discrete sequence x[n]=x(n/fs). The sampling rate fsf_sfs determines the highest frequency you can observe without aliasing: the Nyquist frequency, fs/2. If the analog signal contains energy above fs/2, it does not disappear – it folds back into the band below Nyquist as aliasing. Once aliasing happens, FFT cannot “undo” it; the information is irretrievably mixed. In practice, you must use an anti-alias filter before the ADC (or before any resampling) to suppress components above Nyquist. Example: A 900 Hz sine sampled at fs=1 kHz will appear at 100 Hz in the discrete spectrum – a classic aliasing artifact. DFT Computation and Interpretation Given N samples x[0]..x[N−1], the DFT is defined as: The inverse transform (IDFT) reconstructs the time signal: Intuitively, X[k] tells you how strongly the signal correlates with a complex exponential at that bin’s frequency. The magnitude X[k] indicates “how much” of that frequency component exists The phase encodes time alignment relative to other components What Are You Plotting? Magnitude, Amplitude, Power, PSD From one set of FFT results X[k], you can create many different “spectra” that look similar but represent different physical quantities. This is where confusion between tools and platforms often arises. Common variants include: Magnitude spectrum |X[k]| Units depend on normalization (e.g., “V·samples”) Useful for locating peaks, harmonics, and general spectral shape Amplitude spectrum Properly scaled magnitude, in physical units (e.g. V) Appropriate for reading off sinusoid amplitudes and doing calibrated measurements Power spectrum |X[k]|² Again, scaling dependent; often used for power/energy comparisons when conventions are fixed Power Spectral Density (PSD) Sxx(f) Units like V²/Hz or Pa²/Hz Used for noise analysis, band power, and comparisons across different FFT lengths If you want to compare noise levels across different FFT sizes, windows, or tools, use PSD (or amplitude spectral density). Raw |X| or |X|² values are rarely directly comparable. A Concrete Example: Two Tones in Time and Frequency Imagine a signal consisting of two sinusoids at different frequencies. In the time domain, their sum may look like a “wobbly” waveform. In the frequency domain (FFT/PSD), you will see two distinct narrow peaks at the corresponding frequencies. In OpenTest’s FFT analysis, you can visualise both the spectrum and PSD/ASD side by side, making it easy to: Identify tonal components Inspect noise distribution Compare different operating conditions on the same frequency grid Try it yourself: Download the free OpenTest edition and run an FFT on a simple two-tone signal to see both peaks clearly separated. Window Functions and Spectral Leakage: Cleaning Up Spectra In theory, FFT assumes the sampled block contains an integer number of periods and is then repeated periodically. In reality, the record almost never lines up perfectly with an integer number of cycles. When you repeat that block, you get discontinuities at the boundaries, which causes energy to spread into neighboring bins — this is spectral leakage. To reduce leakage, we typically apply a window function to the time record before doing FFT. A window simultaneously affects: Main lobe width Wider main lobe = peaks get broader → it’s harder to separate close tones Side lobe height Lower side lobes = easier to see small peaks near a large one (better dynamic range) Amplitude/energy scaling Windows change the relationship between a pure tone’s true amplitude and the observed peak, as well as the noise floor level Some practical guidelines: Rectangular window Only use when you can ensure coherent sampling (an integer number of periods in the record) and you want the narrowest possible main lobe Hanning (Hann) window A very robust default choice for general acoustics and vibration work Widely used with Welch/PSD methods Hamming Similar to Hann, with slightly different side-lobe behavior, common in communications Blackman / Blackman–Harris Lower side lobes, useful when you need to see small peaks next to big ones, at the cost of a wider main lobe In OpenTest, you can switch between different window functions in the FFT analysis module and immediately see the impact on peak width, side lobes, and noise floor. Averaging: Making Spectra More Stable For noisy or non-stationary signals, a single FFT can look very “spiky” or unstable. By averaging multiple spectra, you obtain a smoother, more repeatable result. Common averaging types include: Linear averaging A simple arithmetic mean of several FFT results Exponential averaging Recent data gets more weight; good for live monitoring when the spectrum should react but not jump wildly Energy (power) averaging Based on power; ensures power-related quantities remain consistent A good averaging configuration strikes a balance between suppressing random fluctuations and preserving genuine changes in the signal. Where Do We Use FFT in Practice? Audio and Acoustics Typical applications include: Finding feedback frequencies, harmonic distortion, and device noise floors Frequency response (transfer function) measurement Room modes / resonance analysis Spectrograms of speech, music, and equipment noise In audio/acoustics, you must be clear about units and conventions: dB SPL, A-weighting, 1/3-octave bands, etc. FFT is the engine; the reporting convention (reference, weighting, bandwidth) must be clearly defined. Vibration and Rotating Machinery Identifying speed-related peaks (1X, 2X, gear mesh frequencies) Structural resonances and mode behavior under different operating conditions Bearing diagnostics, gear whine, imbalance, misalignment For bearing and gearbox analysis, envelope detection/demodulation is often used: Band-pass filter the signal Demodulate and then perform FFT on the envelope to reveal fault frequencies If the rotational speed is changing, a simple FFT will “smear” peaks. In that case, order tracking or synchronous resampling is more appropriate, turning the axis from “frequency” into “order”. Power Electronics and Power Quality Line frequency harmonics (50/60 Hz and multiples), THD, ripple, switching spikes Pre-compliance EMI checks: spectral lines, noise floor, in-band power In power systems, non-coherent sampling is a common issue: if the record length is not an integer number of mains cycles, leakage affects harmonic accuracy. Solutions include synchronous sampling, integer-cycle windows, or specialized harmonic analyzers. RF and Communications (Baseband View) Modulated signal spectra and spectral masks OFDM and multi-carrier spectral analysis, adjacent channel leakage Here, consistency is paramount: Same units Same bandwidth (RBW) Same window, detector, and averaging style FFT itself is straightforward; turning it into comparable power measurements requires tightly defined settings. Imaging and 2D Filtering 2D FFT extends the same idea to images: Edges correspond to high spatial frequencies; smooth areas to low frequencies Low-pass / high-pass filtering, removal of periodic noise, convolution acceleration in the frequency domain The same periodic extension assumption now applies in 2D: discontinuities at image borders produce strong artifacts in the frequency domain. Padding, mirrored borders, or 2D windows are common ways to mitigate this. Turning FFT into an Everyday Engineering Tool From a mathematical standpoint, FFT is not particularly “lightweight”. But in engineering use, the goal is actually simple: See what’s hidden inside the signal more clearly and much faster. When you understand: What FFT really computes How sampling, windowing, scaling, and averaging affect the result When to use spectra vs PSD, and which settings matter for your use case …then FFT stops being an abstract math topic and becomes a practical, everyday tool for acoustics and vibration work – from R&D and validation all the way to production testing. Download and get started now -> or fill out the form below ↓ to schedule a live demo. Explore more features and application stories at www.opentest.com.

In acoustic measurements (SPL, frequency response, noise, reverberation, etc.), large errors often come not from instrument accuracy, but from a mismatch between the assumed sound field and the actual one. What a microphone reads as sound pressure is not strictly equivalent across different fields—especially at mid and high frequencies, where the microphone dimensions become comparable to the acoustic wavelength. Measurement microphones are commonly categorized by the field for which their calibration/compensation is defined: Free-field, Pressure-field, and Diffuse-field (Random incidence). This article uses engineering-oriented comparison tables and common-pitfall checklists to explain the differences among the three sound-field types, their typical application scenarios, and key usage considerations. It also provides selection rules that can be directly incorporated into test plans, helping to improve measurement repeatability and comparability. Build Intuition With One Picture The following diagrams illustrate the three typical sound-field assumptions used in microphone calibration and selection. Figure 1 Free field: reflections negligible, wave incident mainly from one direction Figure 2 Pressure field: coupler/cavity measurement focusing on diaphragm surface pressure Figure 3 Diffuse (random-incidence) field: energy arrives from many directions (statistical sense) Quick Comparison for Engineering Selection TypeField assumptionTypical scenariosPlacement / orientationMain error driversFree-field microphoneReflections negligible; primarily single-direction incidence (often 0°)Anechoic measurements; on-axis loudspeaker response; front-field SPLAim at source (0°)Angle deviation; unintended reflections; fixture scatteringPressure-field microphoneMeasure true pressure at diaphragm surface (often in small cavities)Couplers; ear simulators; boundary/flush measurementsFlush-mounted or connected to couplerLeaks; cavity resonances; coupling repeatabilityDiffuse-field (random-incidence) microphoneEnergy arrives from all directions with equal probability (statistical)Reverberation rooms; highly reflective enclosures; diffuse-field testsOrientation less critical, but mounting must be controlledNot truly diffuse in real rooms; local blockage/reflections Free Field: Estimate the Undisturbed Sound Pressure A free field is an environment where reflections are negligible and sound arrives mainly from a defined direction (commonly 0° to the microphone axis). Because the microphone body perturbs the field, a free-field microphone typically includes free-field compensation, so the indicated pressure better represents the pressure that would exist without the microphone in place. Typical Use Cases Anechoic or quasi-free-field SPL measurements On-axis loudspeaker frequency response and source characterization Tests with a strictly defined incidence direction Practical Notes Keep 0° incidence when specified; off-axis angles can cause significant high-frequency deviations. Minimize scattering from fixtures (stands, adaptors, fixture、cable、windscreens). Control nearby reflective surfaces that break the free-field assumption. Pressure Field: Measure Diaphragm Surface Pressure A pressure field is commonly associated with small enclosed volumes (couplers/cavities). Here, the quantity of interest is the true pressure at the diaphragm surface. The microphone often becomes part of the cavity boundary. Typical Use Cases Pistonphone/coupler calibration and cavity measurements IEC ear simulators and couplers for headphone and in-ear testing Flush/boundary pressure measurements Practical Notes Seal and coupling are critical; small leaks can strongly affect low and mid frequencies. Cavity resonances can shape high-frequency response; follow the applicable standard or method. Maintain consistent mounting force and assembly for repeatability. Diffuse Field: An Average Over Angles A diffuse field (random incidence) assumes that sound energy arrives from all directions with equal probability, in a statistical sense. This is approached in reverberation rooms or highly reflective enclosures. Diffuse-field microphones are designed so their response better matches the average over many incidence angles. Typical Use Cases Reverberation-room measurements and room acoustics Noise and SPL measurements in reflective cabins (vehicle or enclosure) Statistical measurements where multi-direction incidence dominates Practical Notes A normal room is not necessarily diffuse; strong direct sound breaks the assumption. Proper installation and operation remain essential: large fixtures, mounting brackets, and obstructions can alter the characteristics of the local acoustic field. Keep measurement locations consistent; position changes alter modal and reverberant contributions. Rule of Thumb: Write the Field Assumption into the Test Plan Quasi-anechoic, direction defined → choose a free-field microphone Coupler/cavity/boundary pressure → choose a pressure-field microphone Highly reflective, multi-direction incidence → choose a diffuse-field microphone When the field is uncertain, define the geometry first (direct-to-reverberant ratio, incidence direction, distance), then apply an appropriate calibration or correction strategy to control the dominant error sources. Common Pitfalls Using a free-field microphone in a coupler/cavity: high-frequency deviations are often exaggerated. Free-field testing without controlling angle: off-axis error grows at mid and high frequencies. Treating a normal room as diffuse: if direct sound dominates, the diffuse-field assumption fails. Conclusion Free field, pressure field, and diffuse field are not marketing terms—they tie microphone design and calibration assumptions to specific acoustic models. By explicitly documenting the assumed field (geometry, angle, reflections, calibration and corrections) in your test plan, you can significantly improve repeatability and comparability across measurements. To learn more about microphone functions and measurement hardware solutions, visit our website—and if you’d like to talk to the CRYSOUND team, please fill out the “Get in touch” form.