Measure Sound Better

NEW

Products

Featured Products

Product Lines

Deliver reliable products for acoustic measurement and testing

Sensors

Provides measurement microphones, mouth simulators, ear simulators, and more for accurate acoustic measurements.

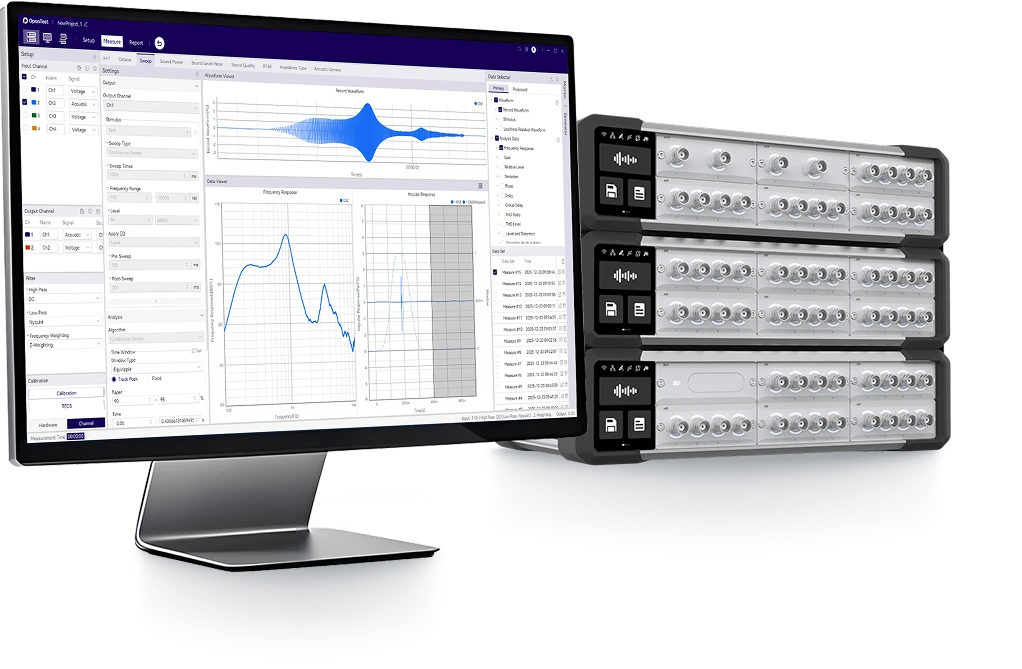

Data Acquisition

Combines hardware and software for high-speed, high-precision signal acquisition, ideal for various acoustic applications.

Acoustic Imaging

Offers acoustic cameras for gas leak detection, partial discharge, and fault diagnostics across handheld, fixed, and UAV platforms.

Noise Measurement

Includes sound level meters, noise sensors, and

monitoring systems for effective noise measurement and analysis.

Electroacoustic Test

Delivers complete electroacoustic testing solutions, including analyzers, testing software, and acoustic test boxes.

Solutions

Provide high-quality solutions for the acoustic field

Monitor all industrial noise and regulate pollution properly, fostering industrial-community harmony.

CRYSOUND provides a shell-type dual-box four-measurement solution for headphone ANC&ENC testing.

In recent years, AR/VR (Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality) technology has

Acoustic imaging technology provides an ultrasonic method for composite airtightness inspection—faster and more reliable.

Blogs

Share insights, cases and trends in acoustic testing

As the core component of measurement chains, the long-term stability of measuring microphones directly impacts the comparability and traceability of measurement data. The 10-year limited warranty (hereinafter referred to as the 10-year warranty) is not merely a service commitment, but a comprehensive capability demonstrated through manufacturing consistency control, reliability verification systems, and traceable evidence chains. This article will outline the engineering implementation approach to explain the rationale behind CRYSOUND's 10-year warranty, and evaluate the impact of this warranty strategy on user lifecycle costs (including maintenance, logistics, downtime, and management costs) based on the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) framework. Economic Value of 10-year Warranty: Budgeting Life Cycle Risk Cost For both laboratories and production lines, the "cost" of microphones constitutes only a fraction of total expenses. The bulk of costs stems from project downtime, retesting and rework, temporary replacements, cross-regional repairs, and administrative complexities. When the warranty period covers a larger portion of the equipment’s service life, users can plan risks and resources more clearly within lifecycle budgets. This is the true value of a Ten-Year Warranty. Engineering Foundation of 10-year Warranty: Reliability Design, Manufacturing and Verification System Manufacturing Process Capability and Consistency Control: Raw Material Validation and 102 Critical Processes Long-term stability primarily stems from consistency. CRYSOUND begins with raw material validation, preemptively identifying and eliminating risks such as corrosion resistance and insulation stability during the incoming material stage. Subsequently, each measuring microphone must undergo 102 stringent processes, with real-time monitoring during precision machining to ensure consistency in critical dimensions and fit. Selection of Critical Materials and Assembly Process Control: Physical Basis of Long-term Stability Key components are assembled by experienced technical experts, utilizing materials with high insulation and low temperature sensitivity to enhance environmental stability. As the core acoustic structure, the third-generation titanium diaphragm technology emphasizes performance objectives such as wide frequency response, high sensitivity, corrosion resistance, and magnetic insensitivity, employing structural and material design to mitigate long-term drift risks. Typical Failure Mechanism and Verification Coverage Matrix The long-term stability of microphones is typically compromised not by a single factor, but by cumulative effects of humidity, temperature, mechanical shocks, and contamination, leading to performance drift or noise degradation. Below is a comparison table illustrating how CRYSOUND maps these typical risks to manufacturing control points and factory verification: Typical risk/failure modeEngineering control pointCorresponding Verification / ScreeningMoisture causes noise to rise sensitivity fluctuationClean Assembly,Insulation Design and Process ControlHigh humidity prolonged test, insulation-related verification (sensitivity pre/post difference / base noise variation / insulation stability)Temperature change-induced driftMaterials and structural stability, assembly consistencyLong-term temperature cycling (sensitivity/frequency response changes, noise trends, structural and connection stability)Structural deflection caused by drop/vibrationStructural strength and assembly processDrop test, bidirectional vibration test (function output stability, key index difference before and after, structural integrity)Pollution/Particulate Matter Causes Noise DegradationUltrasonic cleaning, cleanroom commissioningComprehensive factory noise/performance testing (including noise floor, sensitivity, frequency response consistency, etc.)Corrosion/salt spray leads to reduced appearance and connection reliabilityCorrosion-resistant Material Screening, Surface Treatment and Connector Protection DesignSalt spray exposure/retention + Appearance and connection reliability verification Clean Manufacturing and Pollution Control: Noise and Long-term Stability Fine particles, oil contaminants, and impurities can amplify into noise elevation or performance fluctuations during prolonged use. To mitigate this, each measuring microphone undergoes ultrasonic cleaning and precision calibration in a cleanroom environment, thereby reducing the risk of contamination and foreign object introduction, ensuring low-noise and moisture-resistant performance at the source. Factory Reliability Verification Scheme: Environmental/Mechanical/Electrical Stress Verification A decade-long warranty hinges on systematic coverage of typical service environments and operational conditions. CRYSOUND's factory reliability verification adopts a fundamental approach of "representative environmental and mechanical stress coverage + critical risk coverage," categorizing verification items into three types: environmental stress (humidity, temperature cycling, salt spray), mechanical stress (drop/impact/vibration), and electrical reliability (insulation and leakage risks). This system screens and validates material, assembly, and connection weaknesses through stress coverage of humidity, temperature cycling, salt spray, and drop/vibration conditions before delivery, thereby reducing on-site failure risks. The high-humidity long-term validation examines how humidity affects microphone performance. Under controlled high-humidity conditions, the device undergoes continuous exposure to simulate prolonged moisture exposure, covering risks like insulation degradation, noise performance changes, and stability fluctuations. This is followed by retesting and electrical status verification to confirm the product's stability and consistency under thermal-humidity stress. High and Low Temperature Cycling Validation addresses structural and assembly robustness risks under temperature variation conditions. By conducting prolonged cycles between extreme temperature extremes, it accelerates exposure to potential issues including material thermal expansion differences, stress release, and joint stability. The engineering objective of this validation is to assess performance drift risks and connection/assembly stability under long-term temperature disturbances, thereby reducing the probability of post-delivery anomalies triggered by thermal stress. Salt spray testing addresses material and joint reliability risks in coastal, high-salt, or corrosive environments. By exposing components to controlled salt spray conditions, it evaluates the corrosion resistance of metal parts, joints, and protective designs. The process also includes visual inspection of joints and functional/electrical verification, effectively mitigating corrosion-induced reliability degradation and long-term stability risks. Note: Salt spray validation is used to evaluate the robustness of protection and connection under typical exposure conditions. For long-term operation in harsh environments such as strong corrosion or high salt spray conditions that exceed the product's usage specifications, additional protection measures must be implemented, with the warranty terms as the ultimate reference. Mechanical stress verification (Drop/vibration/Shock) addresses mechanical disturbance risks during transportation, installation, disassembly, and field operation. It involves simulating repeated 1-meter drop handling and accidental impacts through specified cycles, replicating transportation vibrations and prolonged mechanical disturbances via continuous vibration tests, and assessing transient stresses under higher intensity through impact validation. The core objective of mechanical verification is to screen structural integrity, assembly stability, and connection reliability, thereby reducing post-delivery risks of intermittent anomalies and performance variations caused by micro-loosening, connector stress, or assembly misalignment. As a baseline control for electrical reliability, insulation verification addresses risks of leakage, breakdown, or instability caused by moisture, pollution, and material aging. It verifies the insulation performance of critical electrical paths and, when necessary, conducts post-stress environmental reviews to ensure the product maintains stable electrical safety and signal reliability throughout its lifecycle. All aforementioned validation items are implemented in accordance with the company's internal factory inspection specifications, accompanied by procedures for anomaly isolation, re-inspection, and disposal. Products identified with anomalies during the validation process will not proceed to the delivery phase. CRYSOUND 10-year warranty key points Main pointsExplanationScope of applicationApplicable to 3000 series: microphones, preamplifiers, kits, dummy mouthpieces, dummy earpieces, and complete sets (traceable via nameplate/serial number).Warranty Duration DifferencesThe main equipment typically has a lifespan of ten years; accessories/consumables (such as wind shields, cables, connectors, seals, etc.) have a lifespan of six months and should be separately included in the maintenance budget.Start methodPriority is determined by the outbound/delivery date; if no voucher is available, by the end user's purchase date; if still unavailable, by the last date traceable by the factory date or serial number.Warranty contentConfirm material or process defects: Free repair (necessary parts + labor) or replacement with the same model/performance equivalent to the original (possibly certified refurbishment/remanufacturing).Typical non-protectionMisuse/abuse, drop and compression, liquid immersion, corrosive gases/salt spray, overvoltage/reverse connection/ESD/surge, unauthorized disassembly/repair, etc.Calibration apertureCalibration drift within the specified range is a common phenomenon in metrology and does not constitute a manufacturing defect; calibration/recalibration is typically a paid service (unless the drift is confirmed to be caused by a manufacturing defect).Logistics and Cross-borderDefault rule: Users within the warranty scope are responsible for round-trip shipping costs. Cross-border transactions may incur tariffs, customs clearance fees, or taxes, which are typically borne by the user unless otherwise agreed in the contract. Visit https://www.crysound.com/warranty for more information How A Ten-Year Warranty Affects TCO: Cost Structure and Budget Strategy TCO scope and boundary conditions The TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) discussed herein refers to the "total cost" of equipment throughout its lifecycle, encompassing not only the purchase price but also measurement and maintenance, logistics turnover, downtime, and management costs. It is crucial to clarify that warranty coverage addresses "failure risks caused by material/process defects," while calibration/recalibration focuses on "measurement traceability and drift management." Unless testing confirms drift stems from manufacturing defects, calibration/recalibration and measurement certificate updates are typically not covered by free warranty. Users should budget for these as annual predictable costs. Meanwhile, logistics and cross-border costs related to repairs/services should be factored into the TCO calculation upfront. By default, users are responsible for round-trip shipping within the warranty period. Cross-border transactions may incur tariffs, customs clearance fees, or taxes, which are typically borne by the user unless otherwise stipulated in the contract. TCO cost decomposition model and accounting subject A simple model can help you understand the lifecycle cost of a microphone. TCO = Procurement cost + Calibration/recalibration cost + Logistics/cross-border cost + Consumables and accessories replacement + Unplanned downtime/re-testing/rework + Management cost (ledger/compliance/traceability) The Impact of 10-year Warranty on Risk-related Costs: Emergency Expenditure Reduction and Management Cost Optimization Cost reduction for unplanned maintenance/replacement: Material/process defects triggering repairs or replacements are covered by the warranty mechanism, reducing the likelihood of unexpected expenses and emergency procurement. Reduced downtime and retest/rework costs: With enhanced equipment stability and manageable risks during the warranty period, projects experience fewer instances of temporary failures, abnormal fluctuations, or the need for downtime, retesting, or rework. Reduced diagnostic and communication costs: Serial number traceability, historical data, and certificate records can lower localization costs, minimize unnecessary back-and-forth and redundant testing, and enhance processing efficiency. Projected operating costs: annual budget proposal Calibration/Recalibration (annual budgeting recommended): Minor drift in measuring instruments is normal. It is recommended to calibrate at least once every 12 months or as required by the system; verification or recalibration should be performed after high humidity, high temperature, strong vibration, or frequent disassembly and assembly. Supplies/Consumables (replenishment budget recommended): Windproof covers, cables, seals, etc. should be procured according to consumables regulations and replacement cycles to avoid downtime and temporary procurement costs caused by 'small components'. Logistics/International (budget should be allocated separately by scenario): By default, round-trip shipping costs, international customs duties, and clearance fees should be included in advance, especially for multi-location projects and cross-border scenarios. 10-year TCO estimation template Use the table below to quickly build your TCO estimate for procurement or asset inventory: Cost elementInput/AssumptionNotes (How to be affected by the 10-year warranty)Equipment procurementQuantity, Unit Price (RMB per unit)Procurement price is not the whole picture, but it determines the asset baseline Annual calibration/recalibrationFrequency (times/year), per-visit cost (yuan)Typically paid; recommended at least once every 12 monthsAttachments/SuppliesReplacement cycle and unit pricePlan according to the 6-month/consumable ruleLogistics/InternationalRound-trip freight, customs duties and clearanceThe default user assumes responsibility; cross-border scenarios require a separate listingDowntime costCost per outage, annual occurrencesReliability Improvement and Quality Assurance to Reduce the Probability of Unplanned OutagesRetest and reworkSingle rework cost, annual occurrencePerformance and Stability Reduction,Rework and Controversy Cost Accompanying Management of 10-year Warranty: Usage, Calibration and Asset Ledger Asset ledger and traceability information management: serial number—certificate—data association Enter the serial number and model (photograph for archiving), and bind the calibration certificate with factory data. Record critical operating conditions: temperature and humidity, presence of strong vibrations, and frequency of disassembly and assembly. When an exception occurs, prioritize reproducing the standard steps and retaining records (screenshots, waveforms, or comparison data). Usage and Handling Guidelines: Reducing Non-Guarantee Risks Avoid drops, compression, liquid immersion, and corrosive environments; power supply and connections shall be performed in accordance with the instructions. Unauthorized disassembly and repair are strictly prohibited. Ensure the nameplate/serial number is clearly identifiable. Use the original packaging or equivalent protective measures during repair/reinspection, and install protective covers/dust caps on precision interfaces. Repair Information List: Shorten the Location and Processing Cycle Model and serial number photos; purchase/delivery certificates. Fault description (scenario, frequency, environmental conditions, power supply and connection method). Reproducible test records (frequency response, sensitivity, noise, distortion, or system screenshots/waveforms). Conclusion: Ten-year warranty engineering logic and user value The ten-year warranty is built upon a verifiable, traceable, and operational engineering closed loop: reducing consistency risks through manufacturing process capability control, covering typical failure scenarios via environmental and mechanical stress validation, and supporting warranty determination and service efficiency with serial numbers and data records. For users, its value lies not only in fault handling itself but also in reducing the uncertainty of unplanned downtime and emergency replacements, making the lifecycle cost of measurement systems more predictable and easier to incorporate into annual budget management.

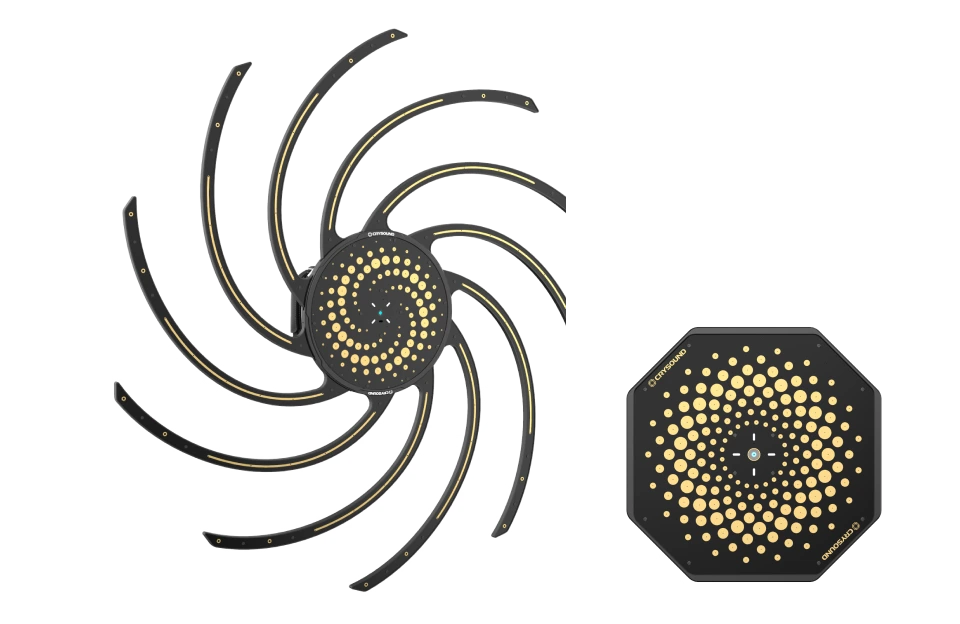

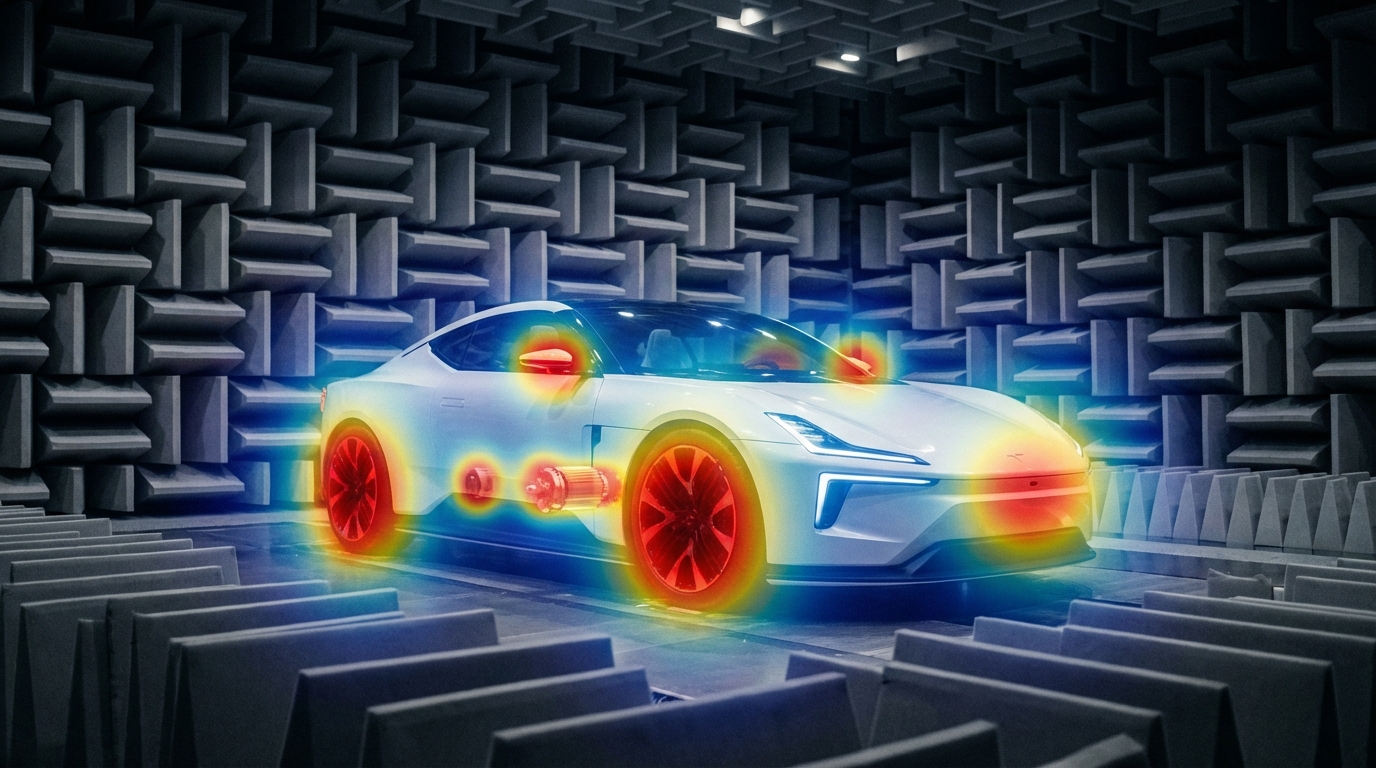

Traditional NVH tools still matter, but they don't cover every EV scenario—acoustic cameras fill the gap with real-time noise visualization and wide-band diagnostics. The Quiet EV Paradox: Why Electric Cars Are Actually "Noisier" It sounds like a paradox — electric vehicles have no roaring engine, yet engineers are finding it harder than ever to achieve a truly quiet cabin. The truth is, when the low-frequency masking effect of the internal combustion engine disappears, every previously hidden noise becomes fully exposed: the high-frequency whine of the electric motor, the electromagnetic hum of the inverter, gear meshing vibrations, wind noise, road noise, even the squeak and rattle of interior trim — nothing can hide anymore. This isn't just a comfort issue. It's fundamentally redefining the automotive industry's approach to NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) testing. The global automotive NVH testing market is projected to grow from USD 3.51 billion in 2026 to USD 5.75 billion by 2034, at a CAGR of 6.4%. The core driver behind this growth? The electrification revolution. What New Noise Challenges Do EVs Bring? A Fundamental Shift in Frequency Range Traditional ICE vehicle NVH work focuses on the 20–2,000 Hz low-frequency range — engine firing, exhaust systems, crankshaft vibrations. Electric vehicles are fundamentally different: Noise SourceTypical Frequency RangeCharacteristicsElectric motor electromagnetic noise500–5,000 HzSharp tonal noise, varies linearly with speedInverter switching noise4,000–10,000+ HzHigh-frequency hum, related to PWM frequencyGear meshing noise800–3,000 HzParticularly prominent in single-speed reducersBattery charger noise8,000–20,000 HzNear-ultrasonic range, at the edge of human perceptionWind / Road noise200–4,000 HzHighly exposed without engine masking ICE vs EV: The fundamental shift in noise frequency characteristics Key insight: EV noise problems shift from low frequencies to mid-high frequencies (and even ultrasonic ranges). The 100Hz-5kHz range is where most critical NVH issues reside—precisely where human hearing is most sensitive. Traditional NVH testing methods and frequency ranges may no longer be sufficient. New Noise Sources, New Localization Challenges In the ICE era, the assumption that "the engine is the dominant noise source" made things relatively straightforward. In EVs, noise sources become more distributed and complex: Electric drive system: The motor + inverter + reducer form a highly coupled noise system Thermal management: Battery cooling pumps and fans become dominant noise sources at low speeds Regenerative braking: Changes in inverter operating modes during energy recovery produce transient noise Structural transmission paths: Lightweight body structures (aluminum alloy, carbon fiber) have fundamentally different sound insulation characteristics compared to traditional steel This means engineers face a core challenge: How do you quickly and accurately locate the root cause among multiple distributed, dynamically changing noise sources? Sound Quality Design: From "Reducing Noise" to "Crafting Sound" NVH engineering in the EV era is no longer just about "minimizing noise." Consumers expect a carefully designed sound experience: Acceleration should feel "high-tech" without being harsh The cabin should be quiet, but not so silent that it makes the driver uneasy Different driving modes (Sport / Comfort / Eco) should deliver differentiated acoustic feedback This demand for "Sound Design" is expanding NVH testing from pure engineering validation into subjective sound quality evaluation and brand-level acoustic identity. Why Acoustic Cameras Are Becoming Essential for EV NVH Facing these new challenges, traditional NVH testing tools — single-point microphones, accelerometers — remain important but are no longer sufficient for every scenario. Acoustic cameras are filling this gap. Core Advantages of Acoustic Cameras 1. Real-Time Noise Source Visualization Traditional methods require densely placing microphone arrays on the target object — time-consuming and labor-intensive. Acoustic cameras use beamforming technology to generate a noise source heatmap in a single capture, instantly showing "where the noise is and how loud it is." Typical scenario: An EV prototype running on a test bench, the acoustic camera aimed at the electric drive system, instantly revealing that an 800 Hz resonance originates primarily from the right side of the motor — the entire localization process takes less than 5 minutes. Engineer conducting noise source localization test Automotive NVH detection and optimization 2. Wide Frequency Coverage EV noise spans from hundreds of hertz (gear meshing) to tens of thousands of hertz (inverter switching noise) — an enormous frequency range. Critical consideration for NVH: Most EV noise issues occur in the 100Hz-5kHz range—gear meshing, motor electromagnetic noise, wind leaks, HVAC systems. Traditional acoustic imaging cameras (limited to frequencies above 5 kHz) cannot capture these noise sources. Take the CRYSOUND SonoCam Pi (CRY8500 Series) as the ideal example: its 208 MEMS microphone array provides: Beamforming frequency range: 400 Hz - 20 kHz (covers the entire NVH audible spectrum) Near-field acoustic holography range: 40 Hz - 20 kHz (captures low-frequency road noise and structural vibration) Array size: >30 cm (optimized for low-frequency spatial resolution) This makes SonoCam Pi uniquely suited for full-spectrum EV NVH testing—from low-frequency road noise to high-frequency motor whine, all in a single handheld device. 3. Non-Contact Measurement EV electric drive systems are highly integrated and spatially compact. The non-contact measurement approach of acoustic cameras means: No disassembly of any components required No interference with the operating state of the system under test Rapid quality inspection directly on the production line 4. Portability Modern handheld acoustic cameras like the SonoCam Pi can be taken directly to proving grounds, production lines, or customer sites, no complex setup required. Typical Application Scenarios in EV NVH ScenarioApplicationE-drive system NVHLocating order-based noise contributions from motors, inverters, and reducersPass-by noise testingAnalyzing noise source distribution as vehicles pass byInterior squeak & rattle trackingLocating noise from dashboards, doors, seats, and trimEnd-of-line production QCRapid online detection of abnormal noise, replacing subjective human judgmentWind tunnel / Semi-anechoic chamberHigh-precision noise source localization and sound power analysis Real-World Case Study: OEM Dynamic Road Testing Client: A leading Chinese OEMLocation: An OEM test center, internal test trackObjective: Identify in-cabin noise sources during dynamic driving conditions CRY8500 Series SonoCam Pi acoustic cameras Test Setup Device:SonoCam Pi acoustic camera Measurement positions:Rear seat and front passenger seat Target areas:Left and right B-pillars (rear cabin area) Test mode:Beamforming app Frequency range:3,550 Hz - 7,550 Hz Dynamic range:5 dB Key Results SonoCam Pi successfully localized noise sources in real-time during vehicle motion, providing actionable data for OEM's NVH engineering team. The test demonstrated: Real-time localization during dynamic conditions: Unlike fixed laboratory setups, SonoCam Pi captured noise distribution while the vehicle was in motion on the test track Precise frequency-band analysis: By focusing on the 3,550-7,550 Hz range (critical for perceived cabin noise), engineers pinpointed specific contributors rather than measuring overall SPL Rapid testing workflow: Complete B-pillar area scan in minutes, not hours Noise Source Localization Results Key Insight: Traditional microphone arrays would require the vehicle to be stationary in a semi-anechoic chamber. SonoCam Pi enabled on-track diagnostics, dramatically reducing testing time and enabling rapid iteration during vehicle development. Future Trends — What's Next for EV NVH Testing? AI-Driven Noise Classification Machine learning is being integrated into NVH testing workflows: automatically identifying noise types, determining whether anomalies exist, and predicting potential quality issues. The high-dimensional data captured by acoustic cameras is naturally suited for AI analysis. Digital Twins and Simulation-Test Integration Simulation (CAE) predicts noise performance → Acoustic camera validates through physical measurement → Data feeds back to optimize the simulation model. This closed-loop approach is becoming the standard workflow for major OEMs. New Challenges in the Solid-State Battery Era Solid-state batteries have different mechanical properties compared to liquid lithium-ion batteries. Their vibration transmission characteristics and thermal management approaches will introduce new NVH challenges. Stricter Regulations Pass-by noise testing is the fastest-growing NVH sub-segment (CAGR 7.11%), with UNECE pushing for stricter standardized testing requirements, including indoor pass-by testing protocols. Conclusion: The Value of Acoustic Testing, Redefined for the EV Era Electrification hasn't made cars quieter — it has made noise challenges more complex, more nuanced, and more valuable to solve. For automotive OEMs, Tier 1 suppliers, and testing service providers, investing in the right NVH testing equipment is no longer a "nice-to-have" — it's foundational infrastructure for competitiveness. Acoustic cameras—especially those capable of capturing the critical 100Hz-5kHz NVH frequency range—are evolving from "useful auxiliary tools" to "indispensable standard equipment." The CRYSOUND SonoCam Pi stands out as the only handheld acoustic camera that combines: Low-frequency capability (400 Hz beamforming, 40 Hz holography) High spatial resolution (208 microphones, >30 cm array) Near-field + far-field measurements in a single system Portability (handheld, <3 kg, production-ready) Learn more: CRYSOUND SonoCam Pi (CRY8500 Series) → Contact us for NVH testing solutions →

You're scanning overhead pipework in a compressor room when a bright hotspot appears on your acoustic camera's display — right on a steel support beam. You walk over, listen carefully, run your hand along the surface. Nothing. No hiss, no vibration, no leak. The screen is showing you a sound source that doesn't exist. Before you question your equipment, take a breath. That phantom hotspot isn't a malfunction. It's physics — and understanding it will make you a significantly better acoustic imaging operator. False positives are an inherent characteristic of how acoustic cameras reconstruct sound fields. Every vendor's product generates them, though the type and severity vary with array design, algorithm quality, and operating environment. Field experience across industrial facilities suggests that 15–30% of initial acoustic imaging indications in reflective environments — plants with metal ducting, concrete floors, and steel enclosures — turn out to be false positives rather than real sources. Most manufacturers avoid this topic entirely. We think that's a mistake, because the engineers who understand false positives don't just avoid misdiagnosis — they use these artifacts to locate sources more effectively. This article covers the three types of false positives you'll encounter, how to identify them, three techniques to minimize them, and — perhaps most importantly — how to turn them into diagnostic allies. What Are False Positives in Acoustic Imaging? False positive (acoustic imaging): An apparent sound source indication on an acoustic camera display that does not correspond to an actual physical source at that location. Caused by physical phenomena including sound wave reflections, beamforming algorithm sidelobes, or environmental noise interference — not by equipment defect. Three related terms often get used interchangeably, but they describe different phenomena: False positive: Any indicated source that isn't real at the shown location Artifact: A systematic error pattern produced by the beamforming algorithm itself (e.g., sidelobes) Ghost image: A reflected or mirrored source — real sound arriving from an indirect path Understanding these distinctions matters because each type has different causes, different on-screen characteristics, and different solutions. Three Types of False Positives Reflections (Ghost Images) Sound waves bounce off hard, smooth surfaces — metal walls, concrete floors, glass panels, polished pipes — just like light reflects off a mirror. When your acoustic camera picks up both the direct sound and the reflected sound, the reflected path appears as a second source at a location where nothing is actually producing noise. Typical scenario: You're imaging a compressed air manifold mounted near a stainless steel wall. The display shows two hotspots — one on the manifold (real) and one on the wall behind it (ghost). The ghost image appears at roughly the same intensity and frequency as the real source. On-screen signature: Ghost images tend to appear at geometrically symmetrical positions relative to the reflecting surface. They share the same frequency spectrum as the real source and often appear at similar or slightly reduced intensity. Sidelobe Artifacts This is the most technically nuanced type. Beamforming algorithms work by mathematically "focusing" the microphone array on each point in the field of view. But just as a flashlight can't produce a perfectly sharp beam edge, beamforming produces a main lobe (the focused area) surrounded by sidelobes — weaker response regions that can register false sources. Typical scenario: You're imaging a single loud leak, but the display shows the main hotspot surrounded by a ring or pattern of secondary spots. These sidelobe artifacts are always clustered around the true source and become more pronounced when the source is loud relative to surrounding noise. On-screen signature: Sidelobes appear as a repeating pattern around the main source — often a ring, halo, or radial spoke pattern. Their intensity is always lower than the main lobe, and they maintain a fixed geometric relationship to the primary source regardless of scanning angle. Key factor: The number of microphone channels directly affects sidelobe levels. A 64-channel array produces more prominent sidelobes than a 128-channel array, which in turn produces more than a 200-channel array. Higher channel counts provide narrower main lobes and lower sidelobe floors. Advanced algorithms like CRYSOUND's HyperVision processing further suppress sidelobes beyond what standard delay-and-sum beamforming achieves. Environmental Noise Interference Not every unwanted indication is a reflection or algorithm artifact. Sometimes, your acoustic camera is accurately detecting a real sound — just not the one you're looking for. Background noise from HVAC systems, nearby machinery, overhead cranes, or even wind can register as apparent sources that get confused with your target. Typical scenario: During a compressed air leak survey in a manufacturing hall, you see multiple hotspots across a wide area. Some are genuine leaks. Others are background machinery noise that happens to fall within your selected frequency band. On-screen signature: Environmental noise sources typically have broader, more diffuse patterns than leaks (which appear as tight, focused hotspots). They also show different frequency characteristics — machinery noise tends to be narrower-band and harmonic, while leak noise is broadband and turbulent. Quick Comparison Type Cause On-Screen Signature Elimination Difficulty Reflections Sound bouncing off hard surfaces Symmetrical ghost image, same frequency as real source Moderate — multi-angle scan + frequency check Sidelobe artifacts Beamforming algorithm side response Ring/halo pattern around main source, lower intensity Low with advanced algorithms (HyperVision) Environmental noise Background machinery in frequency band Diffuse pattern, tonal/harmonic frequency profile Low — frequency filtering + Focus Function How to Identify False Positives: A 4-Step Process When you see an indication you're unsure about, run through these steps before logging it as a confirmed source: Angle change test. Move 2-3 meters to the side and re-scan the same area. Real sources stay in the same physical position on the image. Reflections shift or disappear as you change the angle of incidence. Sidelobes rotate with the main source. Frequency signature check. Switch to spectrum view (if your camera supports it) and examine the frequency profile. Compressed air leaks produce broadband, turbulent noise typically above 20 kHz. Machinery noise has distinct tonal peaks. If the "source" shares an identical spectrum with a known real source nearby, it's likely a reflection. Distance validation. If your camera allows distance-to-source measurement, check whether the indicated distance matches the physical geometry. A reflection off a wall 3 meters behind you will show a source distance that doesn't match the wall's position from your scanning location. Ultrasonic listening. Most acoustic cameras offer a downshift playback feature that converts the directionally-captured ultrasonic signal into audible sound through headphones. Point the camera at the suspect indication and listen. A real compressed air leak produces a distinctive broadband hiss. Sidelobe artifacts and reflections carry no independent acoustic signature — they sound identical to the main source. Environmental noise sounds tonal and harmonic. This lets you verify from your scanning position without walking to the indicated location. Techniques to Minimize False Positives 1. Select the Right Frequency Band Most acoustic cameras allow you to filter by frequency range. Narrowing the band to your target application reduces interference dramatically. For compressed air leaks, focus on 20–50 kHz. For partial discharge, 20–100 kHz. Excluding lower frequencies cuts out most machinery noise. 2. Use Advanced Beamforming Algorithms Not all beamforming is equal. Standard delay-and-sum (DAS) algorithms are computationally simple but produce higher sidelobe levels. Advanced algorithms apply spatial filtering to suppress sidelobes at the processing level. CRYSOUND's HyperVision algorithm, available on the CRY8124 and CRY8120 series, provides up to 10x processing power over standard beamforming, reducing sidelobe artifacts significantly without sacrificing real-time performance. 3. Adopt a Multi-Angle Scanning Protocol Make it standard practice to scan critical areas from at least two different positions. Compare the results. Sources that appear consistently in the same physical location are real. Sources that shift, disappear, or change intensity are false positives. This takes an extra 30 seconds per area and dramatically reduces misdiagnosis. Turning Artifacts into Allies: Using False Positives to Locate Sources Here's where experienced operators separate from beginners. False positives aren't just noise to eliminate — they carry information about the acoustic environment that you can exploit. Reflection Mapping If you see a ghost image on a metal wall, you've just learned something valuable: there's a real sound source at the geometrically mirrored position. The reflection tells you the sound wave's travel path. In complex piping environments where direct line-of-sight to a leak is blocked, reflected images on nearby surfaces can reveal the general direction and approximate distance of sources you can't see directly. Pro technique: When scanning in confined spaces with multiple reflective surfaces, intentionally note where ghost images appear. The pattern of reflections triangulates the true source location, even when the source is behind equipment or above a ceiling panel. Sidelobe Pattern Reading Sidelobes always radiate symmetrically from the main lobe. When you see a sidelobe pattern, the center of that pattern is your real source — guaranteed. In environments where obstructions partially block your view, the visible sidelobes can confirm the direction of a source that's partially hidden. If the sidelobe "ring" is only visible on one side, the true source is on the opposite side, behind whatever's blocking your view. Spatial Focusing (ROI Isolation) In noisy industrial environments, you can't shut down surrounding equipment just to get a cleaner acoustic image. Instead, use your camera's Focus Function: draw a region of interest (ROI) directly on the screen around the area you want to investigate. The camera restricts its beamforming analysis to that region only, effectively suppressing sound sources outside the selected area. This is particularly powerful when combined with frequency band filtering. Narrow the frequency range to your target application (e.g., 20–50 kHz for leak detection), then draw an ROI around the suspect zone. The double filter — spatial plus spectral — dramatically reduces environmental noise interference without requiring any change to the plant's operating conditions. What previously looked like a cluttered display with overlapping hotspots becomes a clean, focused view of the area that matters. Quick Reference Checklist Eliminating false positives: Set correct frequency band for target application Scan from at least two angles Check frequency spectrum of ambiguous sources Use ultrasonic listening to verify auditory signature before logging Leveraging false positives: Note reflection positions to triangulate hidden sources Read sidelobe patterns to confirm source direction Use Focus Function (ROI) to isolate target area from surrounding noise Need help diagnosing false positives? Talk to our application engineers → Frequently Asked Questions How common are false positives in acoustic imaging? Every acoustic camera produces some false positives — it's an inherent characteristic of beamforming physics, not a defect. The frequency and severity depend on the array's channel count, algorithm quality, and operating environment. With proper technique, experienced operators quickly learn to distinguish real sources from artifacts within seconds. Can reflections be completely eliminated? No. As long as there are hard, smooth surfaces in the environment, sound will reflect. However, you can minimize their impact by scanning from multiple angles, using frequency analysis to match spectra, and applying software post-processing. Advanced algorithms reduce reflection sensitivity, but they cannot violate the physics of wave propagation. Does a higher microphone channel count reduce artifacts? Yes. More channels provide a narrower main lobe and lower sidelobe floor. A 200-channel array produces significantly cleaner images than a 64-channel array. This is one of the most meaningful specification differences when comparing acoustic cameras across manufacturers — channel count directly impacts false positive rates. How do I handle false positives in noisy factory environments? Combine three techniques: narrow your frequency band to the target application range (e.g., 20–50 kHz for leak detection, which excludes most machinery noise), use the camera's Focus Function to draw an ROI around the suspect area and suppress surrounding interference, and scan from multiple angles to confirm source persistence. The spatial-plus-spectral double filter handles most noisy environments without requiring any change to plant operations. Can acoustic reflections actually help locate the real source? Yes — and this is an underappreciated technique. Reflections reveal the sound wave's travel path, which means a ghost image on a wall tells you the real source is at the mirrored position relative to that surface. In complex industrial environments with obstructions, deliberately noting reflection patterns can triangulate sources that are not in direct line of sight. About the Author Bowen — Application Engineer at CRYSOUND. Specializing in acoustic imaging diagnostics for industrial maintenance, leak detection, and partial discharge inspection. Combines field experience across power utilities, petrochemical plants, and manufacturing facilities with deep knowledge of beamforming algorithms and array signal processing.

A measurement microphone is not just any microphone — it is a precision acoustic sensor designed for traceable, repeatable sound pressure measurement. This guide covers how they work, the different types available, key specifications to compare, and how to select the right one for your application. What Is a Measurement Microphone? A measurement microphone is a high-precision acoustic transducer engineered to convert sound pressure into an electrical signal with known accuracy. Unlike studio or consumer microphones that are designed to make audio "sound good," a measurement microphone is designed to be truthful — its output must faithfully represent the actual sound pressure at the measurement point. The defining characteristics of a measurement microphone include: Known, stable sensitivity (expressed in mV/Pa) that can be traced to national or international standards Flat, well-characterized frequency response under defined sound-field conditions Wide dynamic range with low distortion from noise floor to maximum SPL Traceable calibration using pistonphones or acoustic calibrators Environmental stability — minimal drift due to temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure changes In practical terms, a measurement microphone is the front-end sensor of a metrology-grade measurement chain. Every specification — from the data acquisition system to the analysis software — depends on the microphone providing an accurate representation of the acoustic environment. For a deeper comparison between measurement and regular microphones, see our article: Differences Between Measurement Microphones and Regular Microphones. How Measurement Microphones Work The Condenser Principle How a condenser measurement microphone converts sound pressure into an electrical signal Nearly all measurement microphones are condenser (capacitor) microphones. The core transduction mechanism is simple but elegant: A thin metallic diaphragm is stretched in front of a rigid backplate, separated by a small air gap The diaphragm and backplate form a capacitor When sound pressure deflects the diaphragm, the gap changes, altering the capacitance With a constant charge on the capacitor, the capacitance change produces a proportional voltage change This voltage change is the microphone's output signal. A preamplifier, typically located immediately behind the capsule, converts the high-impedance signal from the capacitor into a low-impedance signal that can travel through cables to the data acquisition system. Polarization: External vs. Prepolarized Externally polarized (left) vs. prepolarized electret (right) microphone types The condenser principle requires a polarization voltage to maintain a charge on the capacitor. There are two approaches: Externally polarized microphones receive their polarization voltage (typically 200V) from an external power supply through the preamplifier. These microphones are considered the gold standard for the highest-accuracy laboratory measurements because:- The polarization voltage is stable and well-defined- No aging effects from the polarization source- Best long-term stability Prepolarized (electret) microphones use a permanently charged PTFE (Teflon) layer on the backplate to maintain polarization. Advantages include:- No external polarization supply needed — simplifies the signal chain- More resistant to humidity (no risk of charge leakage at high humidity)- Better suited for field measurements and harsh environments- Modern prepolarized microphones achieve accuracy comparable to externally polarized models FeatureExternally PolarizedPrepolarizedPolarization sourceExternal 200V supplyBuilt-in electret layerBest forLab/reference measurementsField and industrial useHumidity toleranceSensitive above ~90% RHExcellent, even in high humidityLong-term stabilityExcellentVery good (modern designs)Signal chainRequires compatible power supplyWorks with standard IEPE/ICP preamplifiers The Preamplifier The preamplifier is a critical but often overlooked component. It serves two functions: Impedance conversion: Transforms the microphone's extremely high output impedance (~GΩ) into a low impedance suitable for cable transmission Signal conditioning: Provides the power for IEPE/ICP operation or the polarization voltage for externally polarized capsules A matched microphone-preamplifier set ensures optimal performance. This is why measurement microphones are often sold as complete sets with a matched preamplifier — the combined system is calibrated and characterized as a unit. Types of Measurement Microphones Measurement microphones are classified along two primary axes: sound-field type and physical size. By Sound-Field Type The choice of microphone type depends on the acoustic environment where measurements will be taken. Free-Field Microphones A free-field microphone is designed to measure sound arriving from a single direction in an environment free of reflections (such as an anechoic chamber or outdoors). The microphone's frequency response is compensated for the acoustic diffraction effects caused by its own physical presence in the sound field. When to use: Outdoor measurements, anechoic chamber testing, source identification, environmental noise monitoring, any scenario where sound arrives predominantly from one direction. Orientation: Point the microphone directly at the sound source (0° incidence). Pressure-Field Microphones A pressure-field microphone measures the actual sound pressure at a surface or in a sealed cavity. It has the flattest possible response when the sound field is uniform across the diaphragm — which occurs in small cavities, couplers, or at surfaces where the microphone is flush-mounted. When to use: Coupler measurements (headphone and earphone testing), hearing aid testing, measurements in small cavities, flush-mounted surface measurements, acoustic impedance measurements. Orientation: The microphone diaphragm is placed at or within the measurement surface. Random-Incidence Microphones A random-incidence (diffuse-field) microphone is optimized for environments where sound arrives from all directions simultaneously — such as reverberant rooms. Its frequency response is a weighted average of responses at all angles of incidence. When to use: Reverberation chamber measurements, environmental noise in reflective spaces, any situation where sound arrives from multiple directions. Microphone TypeSound FieldTypical ApplicationOrientationFree-fieldSound from one directionOutdoor noise, anechoic testing, source IDPoint at sourcePressure-fieldUniform pressure (cavity)Coupler testing, headphones, hearing aidsFlush with surfaceRandom-incidenceSound from all directionsReverberant rooms, diffuse environmentsAny orientation Three microphone types for different acoustic environments: free-field, pressure-field, and random-incidence By Physical Size Measurement microphone capsules come in three standard sizes, each with distinct trade-offs: 1-Inch Microphones The largest standard size. High sensitivity and low noise floor make them ideal for measuring very quiet environments. Sensitivity: ~50 mV/Pa (highest) Frequency range: Up to ~8–16 kHz Best for: Low-frequency and low-level measurements, environmental noise monitoring, building acoustics Limitation: Large size limits upper frequency range due to diffraction effects 1/2-Inch Microphones The most widely used size. Offers a good balance between sensitivity, frequency range, and physical size. Sensitivity: ~12.5–50 mV/Pa Frequency range: Up to 20–40 kHz Best for: General-purpose acoustic measurements, NVH testing, product R&D, sound level meters Why it's popular: Versatile enough for most applications; fits standard sound level meter bodies 1/4-Inch Microphones The smallest standard size. Low sensitivity but the widest frequency range. Sensitivity: ~1.6–16 mV/Pa Frequency range: Up to 40–100 kHz Best for: High-frequency measurements, ultrasonic applications, small coupler measurements, acoustic array elements Trade-off: Higher noise floor requires louder sound sources for accurate measurement Size comparison: 1-inch (CRY3101), 1/2-inch (CRY3203), and 1/4-inch (CRY3401) measurement microphone capsules SizeSensitivity (typical)Frequency RangeDynamic RangeBest For1 inch50 mV/Pa4 Hz – 16 kHz15–146 dBALow-frequency, quiet environments1/2 inch12.5–50 mV/Pa3 Hz – 40 kHz16–164 dBAGeneral-purpose, NVH, SLM1/4 inch1.6–16 mV/Pa4 Hz – 100 kHz32–174 dBAHigh-frequency, ultrasonic, arrays Key Specifications Explained When comparing measurement microphones, these specifications matter most: Sensitivity Sensitivity defines how much electrical output the microphone produces for a given sound pressure. Expressed in mV/Pa (millivolts per Pascal) or dB re 1V/Pa. Higher sensitivity = better signal-to-noise ratio at low sound levels Lower sensitivity = higher maximum SPL before distortion There is always a trade-off between sensitivity and maximum SPL Frequency Response The frequency range over which the microphone provides accurate measurements, typically specified within ±2 dB or ±1 dB. The useful range depends on:- Microphone size (smaller = wider range)- Sound-field type (free-field compensation extends the useful range)- Mounting configuration Dynamic Range The span between the lowest measurable level (noise floor) and the highest level before a specified distortion threshold (typically 3% THD). A wider dynamic range means the microphone can handle a greater variety of measurement scenarios. Self-Noise (Equivalent Noise Level) The inherent electrical noise of the microphone, expressed as an equivalent sound pressure level in dBA. Lower is better — critical for measuring quiet environments. 1-inch microphones: ~15–18 dBA (quietest) 1/2-inch microphones: ~16–28 dBA 1/4-inch microphones: ~32–46 dBA Stability and Temperature Coefficient Long-term sensitivity drift and sensitivity change with temperature. Important for:- Permanent monitoring installations (fixed outdoor microphones)- Measurements in extreme environments (engine test cells, climatic chambers)- Ensuring measurement results are comparable over months or years IEC Standards Compliance Measurement microphones are classified according to IEC 61094 series:- IEC 61094-1: Primary calibration by reciprocity method- IEC 61094-4: Specifications for working standard microphones (laboratory use)- IEC 61094-5: Working standard microphones for in-situ (field) use Sound level meters incorporating measurement microphones must comply with:- IEC 61672-1: Class 1 (precision) or Class 2 (general purpose) How to Choose the Right Measurement Microphone How to select the right measurement microphone for your application Step 1: Identify Your Sound Field Your Measurement ScenarioRecommended TypeOutdoor environmental noiseFree-fieldAnechoic chamber testingFree-fieldHeadphone/earphone couplerPressure-fieldHearing aid testingPressure-fieldReverberant roomRandom-incidenceSurface-mounted on a machinePressure-fieldGeneral factory noiseFree-field or random-incidence Step 2: Determine Required Frequency Range ApplicationMinimum Frequency RangeBuilding acoustics20 Hz – 8 kHzEnvironmental noise20 Hz – 12.5 kHzGeneral acoustic testing20 Hz – 20 kHzNVH (automotive)20 Hz – 20 kHzElectroacoustic product testing20 Hz – 40 kHzUltrasonic measurements20 Hz – 100 kHz Step 3: Match the Dynamic Range to Your Environment Quiet environments (recording studios, anechoic chambers): Choose high-sensitivity microphones (50 mV/Pa, 1/2" or 1") with low self-noise Industrial environments (factory floors, engine test cells): Choose lower-sensitivity microphones (4–12.5 mV/Pa, 1/4" or 1/2") with high maximum SPL Wide-range applications: Choose microphones with the widest dynamic range available Step 4: Consider Environmental Conditions High humidity or outdoor use: Prepolarized microphones are recommended Extreme temperatures: Check the microphone's operating temperature range and temperature coefficient Dusty or wet environments: Look for IP-rated solutions (e.g., IP67 for NVH field testing) Hazardous areas: Check for ATEX/IECEx certification if required Step 5: Evaluate the Complete System A measurement microphone does not work alone. Consider:- Preamplifier compatibility: Matched sets ensure specified performance- Data acquisition system: Input impedance, voltage range, and sampling rate must match- Calibration infrastructure: Do you have access to a pistonphone or acoustic calibrator?- Software ecosystem: Can your analysis software import calibration data and apply corrections? Applications Electroacoustic Product Testing Testing loudspeakers, headphones, earphones, and hearing aids requires microphones that can accurately capture the device's frequency response, distortion, and directivity. Pressure-field microphones are used in couplers (IEC 60318 ear simulators), while free-field microphones are used in anechoic chambers. Automotive and Aerospace NVH NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) engineers use measurement microphones to characterize cabin noise, identify noise sources, evaluate sound packages, and perform transfer path analysis. Requirements include wide frequency range, high dynamic range, and robustness for field use. Environmental and Community Noise Monitoring Long-term outdoor noise monitoring stations require microphones with excellent stability over months or years, low temperature sensitivity, and tolerance to humidity, rain, and wind. Windscreens and weather protection accessories are essential. Production Line Quality Control In manufacturing, measurement microphones integrated into automated test systems verify that every loudspeaker, headphone, or microphone meets specifications before shipping. Speed, repeatability, and consistency are critical — the microphone must produce identical results across thousands of units per day. Building and Architectural Acoustics Measuring reverberation time, sound insulation, and HVAC noise requires accurate low-frequency performance and the ability to work in diffuse sound fields. Random-incidence microphones are often preferred. Acoustic Research and Standards Laboratories Primary and secondary calibration laboratories, standards organizations, and university research groups require the highest-accuracy microphones — typically externally polarized, laboratory-grade capsules calibrated by reciprocity methods. Sound Source Localization and Beamforming Microphone arrays used in acoustic cameras and beamforming systems require large numbers of measurement microphones with tightly matched sensitivity and phase response. 1/4-inch microphones are preferred for arrays due to their small size and wide frequency range. For more on acoustic imaging technology, see our guide on acoustic cameras. Noise Regulation Compliance Regulatory compliance measurements — workplace noise (ISO 9612), environmental noise (ISO 1996), product noise emission (ISO 3744/3745) — require Class 1 or Class 2 measurement microphones as specified in IEC 61672. Documentation of calibration traceability is mandatory for compliance reporting. CRYSOUND Measurement Microphone Solutions CRYSOUND's CRY3000 series measurement microphones cover the full range of sizes, field types, and applications — from laboratory reference measurements to rugged field testing. Complete Size Coverage: 1/4", 1/2", and 1" ModelSizeField TypeSensitivityFrequency RangeApplicationCRY3101-S011"Free-field50 mV/Pa4 Hz – 16 kHzLow-frequency, quiet environmentsCRY3203-S011/2"Free-field50 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 20 kHzGeneral acoustic testingCRY3261-S021/2"Free-field450 mV/Pa10 Hz – 16 kHzUltra-high sensitivityCRY3201-S011/2"Free-field12.5 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 40 kHzExtended high-frequencyCRY3401-S011/4"Free-field15.8 mV/Pa4 Hz – 40 kHzHigh-frequency testingCRY3403-S011/4"Free-field4 mV/Pa4 Hz – 90 kHzUltrasonic measurementsCRY3202-S011/2"Pressure12.5 mV/Pa3.15 Hz – 20 kHzCoupler and cavity testingCRY34021/4"Pressure1.6 mV/Pa4 Hz – 100 kHzHigh-frequency pressure fieldCRY3406-S011/4"Pressure15.8 mV/Pa4 Hz – 40 kHzLow-noise pressure field CRY3213: Purpose-Built for NVH The CRY3213 NVH Measurement Microphone is specifically designed for the demanding conditions of automotive and industrial NVH testing: IP67 protection: Fully dust-tight and submersible — operates reliably in engine bays, test tracks, and climatic chambers Extended temperature range: -50°C to 125°C, covering extreme hot and cold testing scenarios Free-field response: 3.15 Hz to 20 kHz, optimized for the frequency range relevant to cabin noise, powertrain NVH, and road noise 50 mV/Pa sensitivity: High enough for quiet cabin measurements, robust enough for engine noise Matched Microphone-Preamplifier Sets Every CRYSOUND measurement microphone set includes a matched preamplifier, factory-calibrated as a complete system. This eliminates the guesswork of mixing microphones and preamplifiers from different sources, and ensures that the combined frequency response, noise floor, and dynamic range meet the published specifications. Calibration and Traceability All CRYSOUND measurement microphones ship with individual calibration certificates traceable to national standards. For ongoing measurement assurance, see our guide on measurement microphone calibration. Explore CRYSOUND Measurement Microphones → Frequently Asked Questions What is the difference between a measurement microphone and a regular microphone? A measurement microphone is designed for accuracy and traceability — its output must truthfully represent the sound pressure at the measurement point. A regular microphone is designed for audio quality, often with intentional frequency shaping to enhance speech clarity or musical timbre. For a detailed comparison, read Measurement vs. Regular Microphones. Do I need to calibrate my measurement microphone? Yes. Regular calibration — at minimum before each measurement session using an acoustic calibrator — ensures your results are accurate and traceable. Periodic laboratory recalibration (typically annually) verifies long-term stability. Learn more about microphone calibration. Can I use a 1/2-inch microphone for ultrasonic measurements? Standard 1/2-inch microphones typically reach up to 20–40 kHz, which is insufficient for many ultrasonic applications. For measurements above 40 kHz, a 1/4-inch microphone is recommended — models like the CRY3403 reach 90 kHz, while the CRY3402 reaches 100 kHz. What does "free-field" vs. "pressure-field" mean? A free-field microphone is optimized for measuring sound arriving from one direction in open space. A pressure-field microphone is optimized for measuring sound pressure in enclosed cavities or at surfaces. The difference is in how the microphone compensates for acoustic diffraction effects at high frequencies. How do I choose between externally polarized and prepolarized? For laboratory reference measurements in controlled environments, externally polarized microphones offer the best long-term stability. For field measurements, industrial applications, or environments with high humidity, prepolarized microphones are more practical and equally accurate with modern designs. What IP rating do I need for outdoor or industrial use? For NVH field testing and outdoor measurements, IP67 (dust-tight, waterproof) provides the best protection. The CRY3213 is specifically designed for these conditions. For general lab use, IP protection is typically not required. Need help selecting the right measurement microphone for your application? Contact CRYSOUND for expert guidance based on your specific measurement requirements.