Measure Sound Better

Ways to Connect a DAQ to a PC: Ethernet, USB, Wi-Fi, and PXIe

Table of content

Before you begin any formal data acquisition work, one critical step is connecting the DAQ front end to the PC. In day‑to‑day engineering, the most common options include USB direct connection, Wi‑Fi wireless, Ethernet, and PXIe. This article introduces these four common connection methods from several angles—how they differ, where each one shines, and their practical limitations—to help you build a deeper, more intuitive understanding of DAQ connectivity.

Ethernet Connection

An Ethernet connection means the front end joins a local area network (LAN) through its network port, and the PC accesses the device over IP.

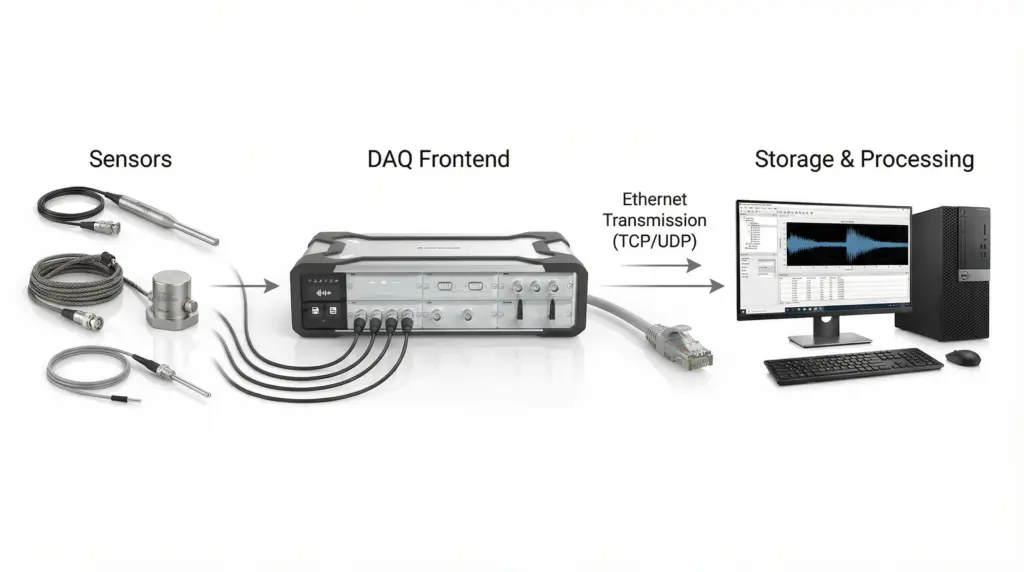

A typical data path looks like this:

Sensor → front‑end sampling → Ethernet transport (TCP/UDP, etc.) → PC/server storage and processing.

This topology ranges from very simple to quite complex, for example:

- Front end ↔ PC (point‑to‑point direct link)

- Multiple front ends → switch → PC/server (distributed)

Figure 1. Ethernet Connection

Advantages of Ethernet Connections

- Flexible topology: single‑node, multi‑node, and distributed setups are all easy to organize;

- Comfortable distance and cabling: copper Ethernet or fiber makes it easier to deploy across rooms, floors, or even buildings—and routing can be more standardized;

- Mature infrastructure and strong maintainability: switches, cables, transceivers, fiber, and rack accessories are widely available, and issues are usually easier to locate and troubleshoot;

Limitations of Ethernet Connections

- The network introduces uncertainty—topology, switch performance, port congestion, broadcast storms, and link errors can all cause throughput/latency fluctuations;

- With multiple devices/nodes, the need for network planning rises quickly: IP addressing, subnetting, whether to use DHCP, routing across subnets, switch cascade depth, etc. As the system grows, things can get messy without a plan.

- Cable quality, shielding/grounding, routing close to high‑power lines, poor port contact, or switch power instability may show up as packet loss, retransmissions, or speed‑negotiation anomalies.

For engineers, Ethernet is straightforward on the test floor: in many setups, a single cable is enough to bring the DAQ front end online with the PC—parameter setup, start/stop, live monitoring, and logging all feel smooth. When the distance grows, you can extend the copper run or switch to fiber to keep transmission stable. In cross‑floor or multi‑room environments—or where noise/safety constraints make it inconvenient to stay near the rig—data can be acquired and monitored from an office or control room over the network. Of course, very long cable runs can be a headache in their own right.

SonoDAQ Pro comes standard with two Gigabit LAN ports (GLAN, daisy‑chain capable, supporting 90 W PoE++ power delivery) and also provides a USB‑C port with gigabit‑class throughput, giving users more flexible network‑style connection options.

Figure 2. SonoDAQ Rear Panel

Wi‑Fi Connection

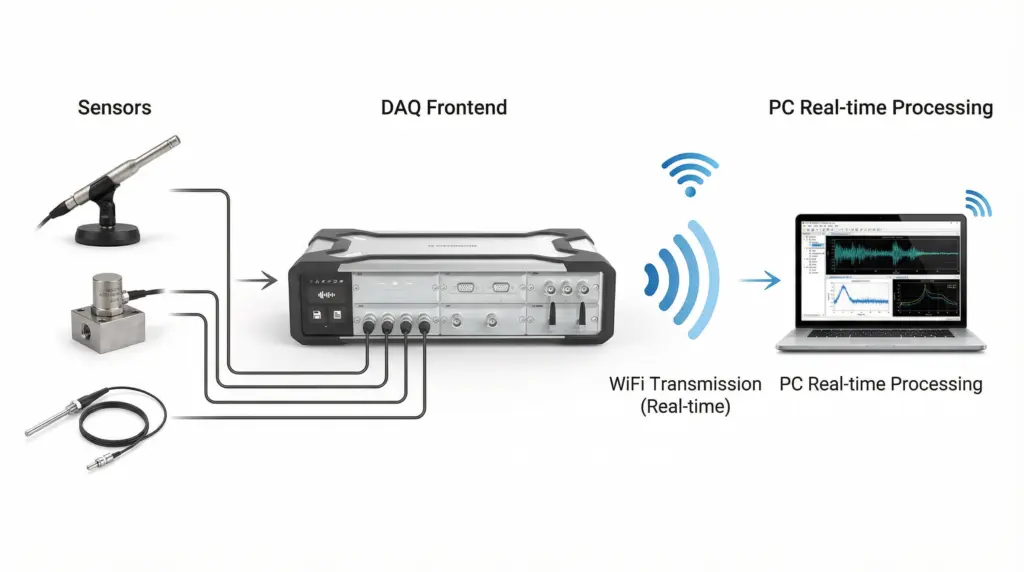

Wi‑Fi DAQ means the acquisition node communicates with a PC or a LAN over a wireless network. Unlike simply “replacing the cable with wireless,” Wi‑Fi DAQ systems typically have two working modes:

- Real‑time streaming: after sampling, data is sent to the PC over Wi‑Fi in real time;

- Local buffering/storage: data is first buffered or stored on the front end; Wi‑Fi is used mainly for control, preview, transferring selected segments, or exporting after the run.

Two common networking setups are:

- The DAQ front end joins an on‑site access point (STA mode);

- The PC creates a hotspot and the DAQ front end connects to it.

In short, the front end must support Wi‑Fi, and it must be on the same LAN as the PC.

Figure 3. Wi-Fi Connection

Advantages of Wi‑Fi Connections

- No cabling: when wiring is difficult or not allowed, the DAQ can be placed close to the measurement point and controlled over Wi‑Fi;

- Flexible remote acquisition: by mapping the DAQ’s IP to the public Internet, the PC can access the DAQ by IP address for ultra‑long‑distance remote control.

Limitations of Wi‑Fi Connections

- Uncertainty for sustained high‑volume transfers: available wireless bandwidth can change at any time, so long, continuous acquisitions are more likely to expose packet loss/retransmissions/buffer overflows—the heavier the data load, the more obvious this becomes;

- Stability depends heavily on the environment: multipath, co‑channel interference, AP congestion, and movement (changing the RF path) can all cause throughput swings and higher latency/jitter, showing up as choppy live plots or occasional disconnect/reconnect events.

In real projects, Wi‑Fi is most often used when cabling is inconvenient or prohibited, or when remote/off‑site acquisition is required but running Ethernet is impractical. Engineers can configure parameters remotely, start/stop acquisition, monitor key metrics, or pull specific segments. For larger datasets or long‑duration logging, it’s common to pair Wi‑Fi with front‑end buffering/local storage—Wi‑Fi keeps things visible and controllable, while the front end protects data integrity.

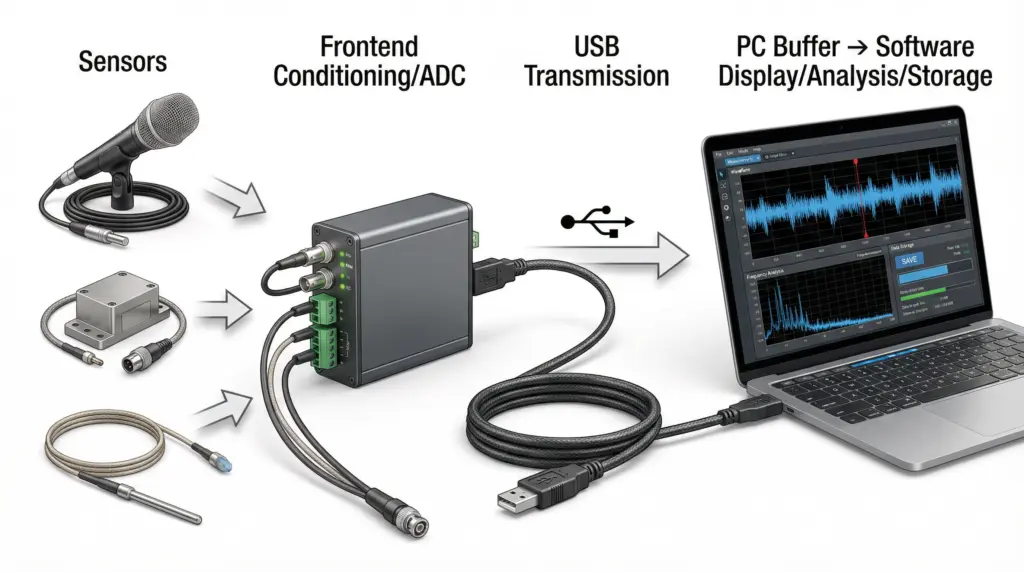

USB Connection

A USB DAQ device typically means sampling happens in an external front end (with built‑in ADCs, signal conditioning, clocks, etc.). The PC handles configuration, visualization/analysis, and data storage, while USB “moves” the data into the computer. In this relationship, the PC acts as the USB host and the front end acts as the USB device.

Figure 4. USB Connection

Advantages of USB Connections

- Low barrier and quick to start: no IP setup and no dependency on network infrastructure—plug it in, install the driver/software, and you can usually start acquiring;

- Highly portable: an external box plus a laptop is a common combo, well suited to field work, customer sites, and temporary setups;

- Ubiquitous interface: cables, adapters, mounting clips, and docks are easy to source;

Limitations of USB Connections

- Scalability is generally less “natural” than network/platform approaches. When a system grows from a single front end to multiple front ends and coordinated multi‑point measurements, cabling, device management, and synchronization depend more on the specific implementation;

- If multiple high‑throughput devices share the same USB controller (DAQ front end, external SSD, camera, etc.), you may see throughput fluctuations, buffer warnings, and occasional stuttering.

- USB controllers, driver stacks, system load, and power‑management policies vary from PC to PC, so the same device can behave differently on different hosts.

Most USB front ends are portable external devices. They often integrate a reasonably complete set of general‑purpose measurement interfaces—analog inputs/outputs, digital I/O, counters/encoders, etc. With a single USB cable, you get both connection and control to the PC for acquisition, display, and storage. As a result, USB is widely used for temporary measurements in the field or at customer sites, rapid R&D bring‑up and debugging, and small‑channel, short‑duration tests.

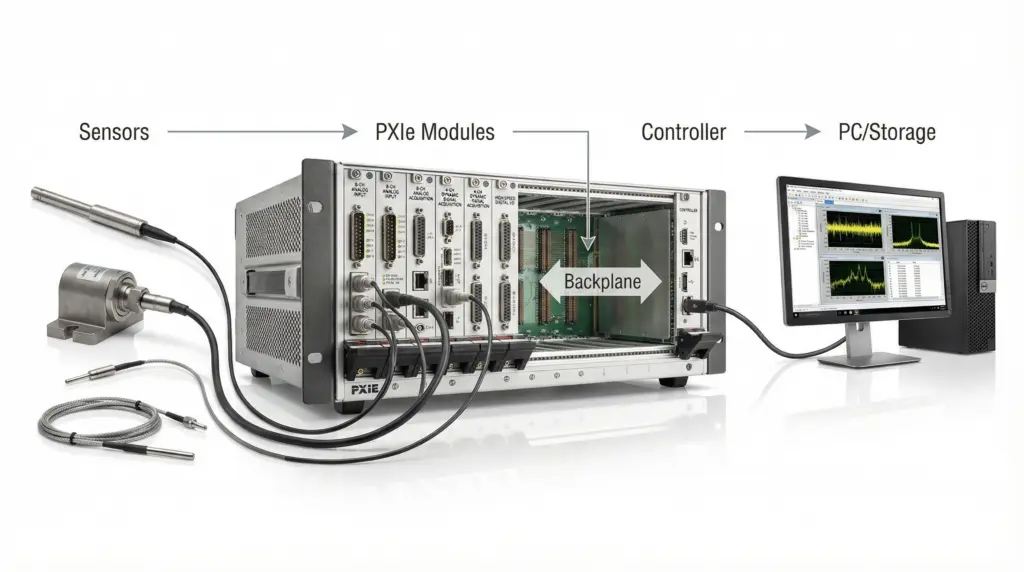

PXIe Interface

PXIe is a platform form factor built around a chassis, backplane, and modules. Measurement/instrument modules plug into the chassis and interconnect through the backplane; the chassis then works with a controller or an external link to a PC workstation. Compared with a single external DAQ box, PXIe is more platform‑oriented, modular, and capable of system‑level composition.

If a PXIe controller is installed in the chassis, the chassis effectively becomes the host and can run acquisitions independently.

Without a PXIe controller, a PXIe chassis is typically not connected to a PC via a standard Ethernet port. Instead, it uses a remote‑control link that essentially “extends the PCIe bus” so an external PC can see the chassis modules as if they were local PCIe devices. In practice, the two most common options are MXI‑Express (a host interface card in the PC plus a remote‑control module in the chassis, linked with a dedicated cable) and Thunderbolt.

A typical data path looks like this:

Sensor → PXIe module sampling/processing → chassis backplane → controller/link → PC/storage

Figure 5. PXIe interface

Advantages of PXIe Interface

- You can populate the chassis with the functional modules you need (analog, digital, bus interfaces, switch matrices, etc.). System capability comes from the “module mix,” and adding or swapping modules later is straightforward;

- High level of engineering integration: power, cooling, and mechanical form factor feel more like a test platform. In rack/bench systems, cabling, maintenance, and spare‑parts management are easier to standardize;

- When a test system is expected to evolve—more channels, more functions, module upgrades over time—the platform’s long‑term scalability is a strong advantage.

Limitations of PXIe Interface

- Higher cost and larger footprint: a chassis + module ecosystem is typically a bigger investment than “PC + single card/box,” and it tends to be a fixed installation.

- Less friendly for mobile/field work: for scenarios that require frequent transport and rapid setup, PXIe’s platform advantages can become a burden;

- Higher system‑build complexity: it’s more like building a test system, where rack layout, harness management, thermal design, power headroom, and grounding all need to be considered.

In practice, SonoDAQ Pro adopts a PCIe‑based modular backplane architecture. Each functional module connects to the main control platform (ARM) through the backplane for high‑speed data uplink/downlink, synchronization, and power distribution. We call this internal interconnect “Trilink.” While enabling modular expansion, SonoDAQ Pro also supports external communication interfaces such as GLAN, Wi‑Fi, and USB‑C, significantly improving deployment flexibility.

For a more hands‑on view of how SonoDAQ works over different connection methods (USB / Wi‑Fi / GLAN)—including real usage workflows, representative scenarios, and common configuration checklists—please fill out the Get in touch form below and we’ll reach out shortly.

Related Products

SonoDAQ Pro

OpenTest

CRY3213 NVH Measurement Microphone

CRY3018 Sound Calibrator

Get in touch

If you are interested or have questions about our products, book a demo and we will be glad to show how it works, which solutions it can take part of and discuss how it might fit your needs and organization.

.112_结果_结果_2-scaled-3-300x208.webp)