Measure Sound Better

Octave-Band Analysis: The Mathematical and Engineering Rationale

Table of content

Octave-band analysis converts detailed spectra into standardized 1/1- and 1/3-octave bands using constant-percentage bandwidth on a logarithmic frequency axis. In this post, we explain the mathematical basis of CPB, why IEC 61260-1 and ANSI S1.11 define octave bands the way they do, and how band levels are computed in practice (FFT binning vs. filter-bank RMS). The goal: repeatable, comparable results for acoustics, NVH, and compliance measurements.

What is octave-band analysis, and what problem does it solve?

Octave-band analysis is a family of spectrum analysis methods that partition the frequency axis on a logarithmic scale into band-pass bands. Each band has a constant ratio between its upper and lower cut-off frequencies (constant percentage bandwidth, CPB). Within each band we ignore fine line-spectrum details and focus on total energy / RMS (or power) in that band.

In other words, it is not “what happens at every 1 Hz,” but “how energy is distributed across equal relative bandwidths.”

This representation naturally matches human hearing and many engineering systems, whose frequency resolution is often closer to a relative (log) scale than a fixed-Hz scale.

- It is a common reporting format required by many standards: room acoustics parameters, sound insulation ratings, environmental noise, machinery noise, wind/road noise, etc., often use 1/3-octave bands.

From linear Hz to log frequency: why CPB looks more like an engineering language

Using equal-width frequency bins (e.g., every 10 Hz) to accumulate energy leads to inconsistent behavior across the spectrum:

- At low frequencies, a 10 Hz bin may be too wide and can smear details.

- At high frequencies, a 10 Hz bin may be too narrow, giving higher variance and less stable estimates for random noise.

In contrast, CPB bandwidth grows with frequency (Δf ∝ f). Each band covers a similar relative change, improving stability and repeatability—important for standardized testing.

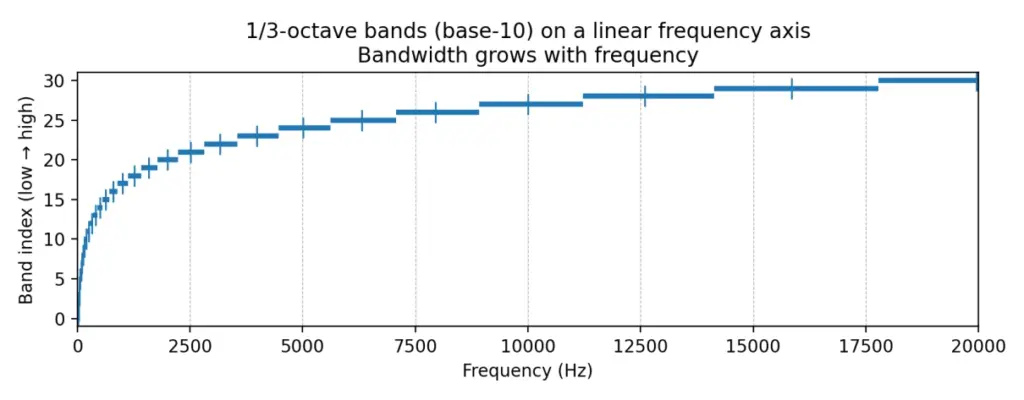

A visual intuition: bandwidth increases on a linear axis, but is uniform on a log axis

Figure 1: the same 1/3-octave bands plotted on a linear frequency axis—bandwidth appears larger at high frequencies

Each horizontal segment represents a 1/3-octave band [f1, f2]; the short vertical mark is the band center frequency fm. On a linear axis, higher-frequency bands look wider.

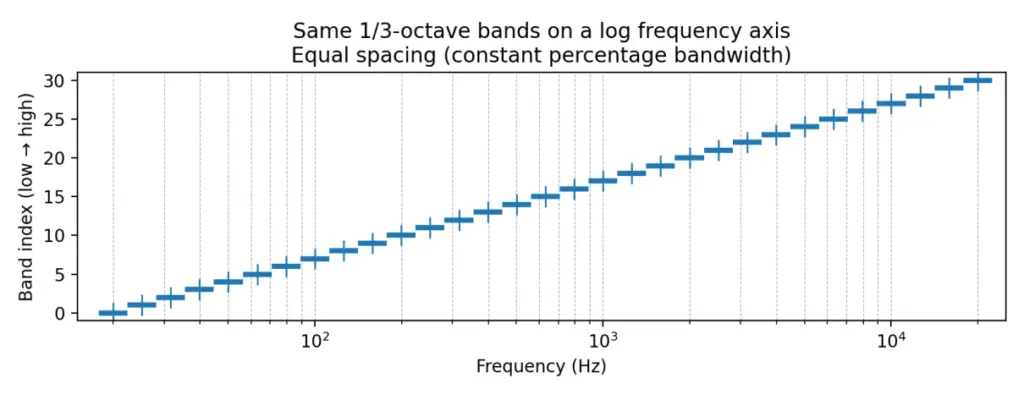

Figure 2: the same bands on a logarithmic frequency axis—bands become evenly spaced (the essence of CPB)

Once the horizontal axis is logarithmic, these bands appear equal-width/equal-spacing; this is exactly what “constant percentage bandwidth” means.

These two figures capture the core idea: octave-band analysis uses equal steps on a log-frequency scale, not equal steps in Hz.

Standards and terminology: what do IEC/ANSI/ISO systems actually specify?

In practice, “doing 1/3-octave analysis” is constrained by more than just band edges. Standards specify (or strongly imply): how center frequencies are defined (exact vs nominal), the octave ratio definition (base-10 vs base-2), filter tolerances/classes, and even the measurement/averaging conventions used to form band levels.

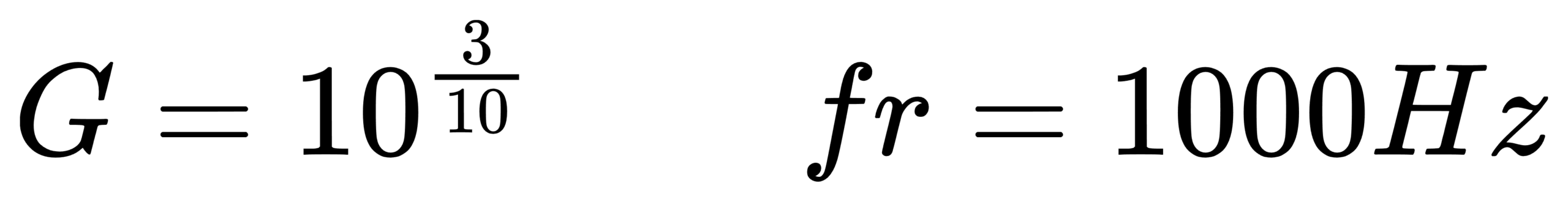

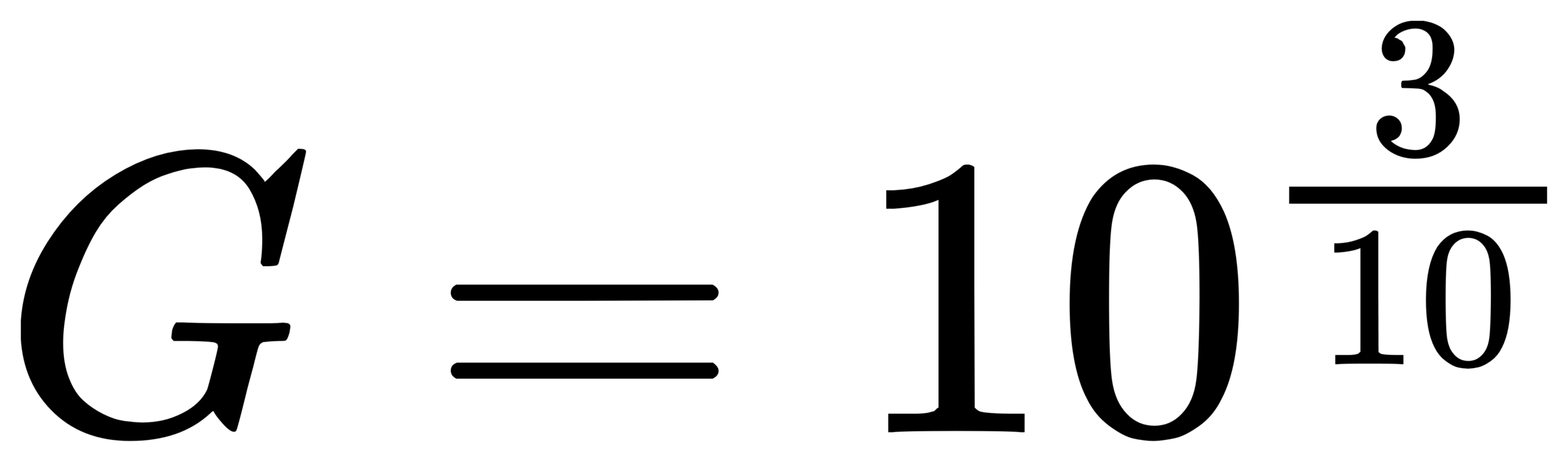

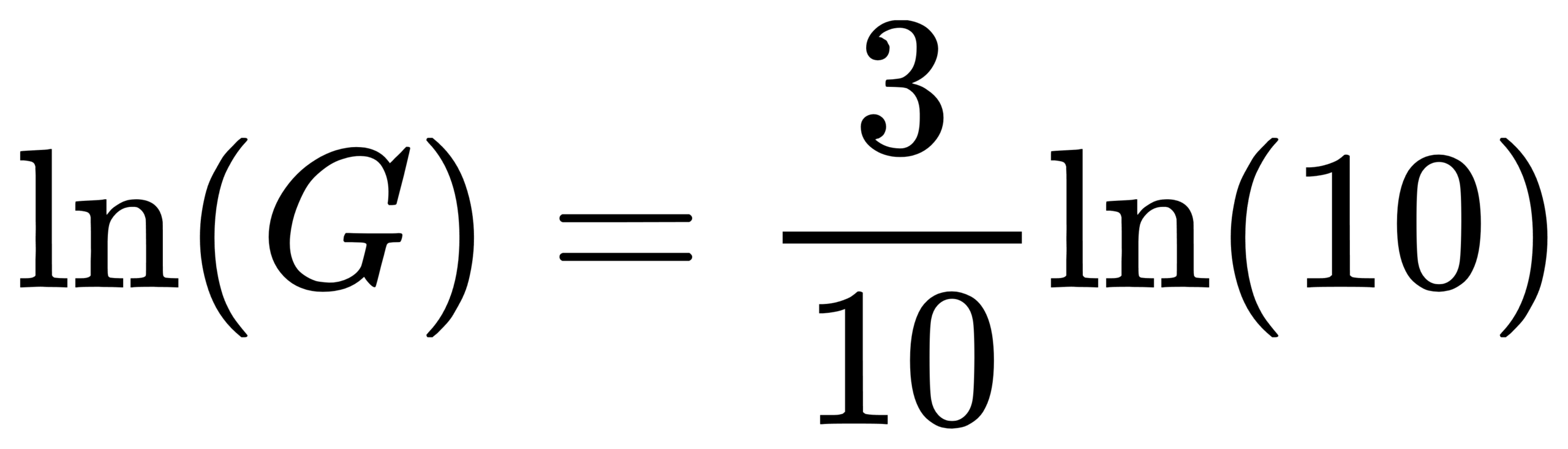

IEC 61260-1:2014 highlights: base-10 ratio, reference frequency, and center-frequency formulas

IEC 61260-1:2014 is a key specification for octave-band and fractional-octave-band filters. It adopts a base-10 design: the octave frequency ratio is G = 10^(3/10) ≈ 1.99526 (very close to 2, but not exactly 2). The reference frequency is fr = 1000 Hz. It provides formulas for the exact mid-band (center) frequencies and specifies that the geometric mean of band-edge frequencies equals the center frequency. [1]

Key formulas (rearranged from the standard): [1]

If the fractional denominator b is odd (e.g., 1, 3, 5, ...):

If b is even (e.g., 2, 4, 6, ...):

And always:

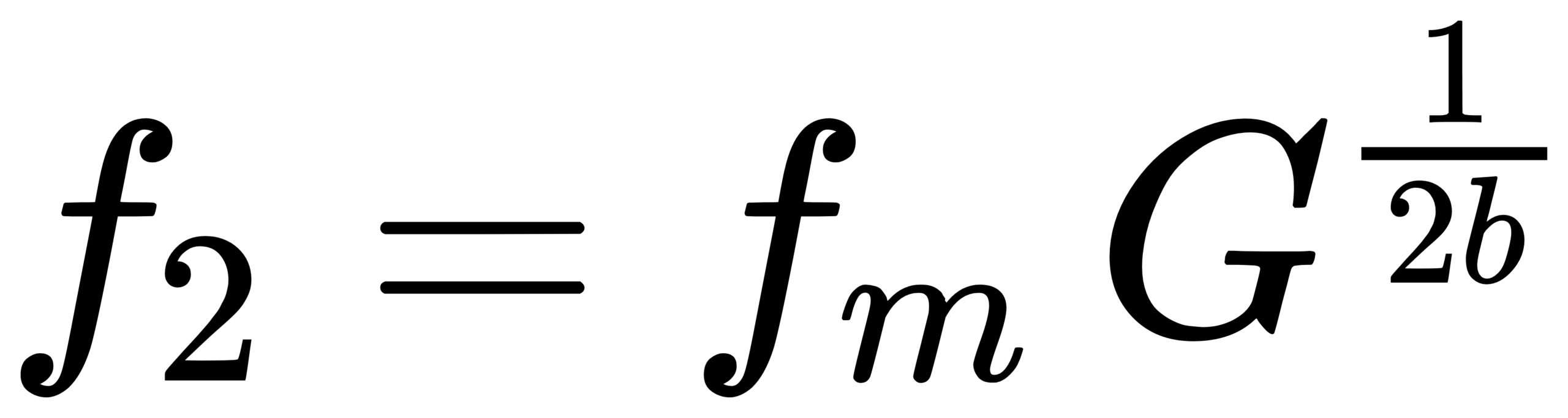

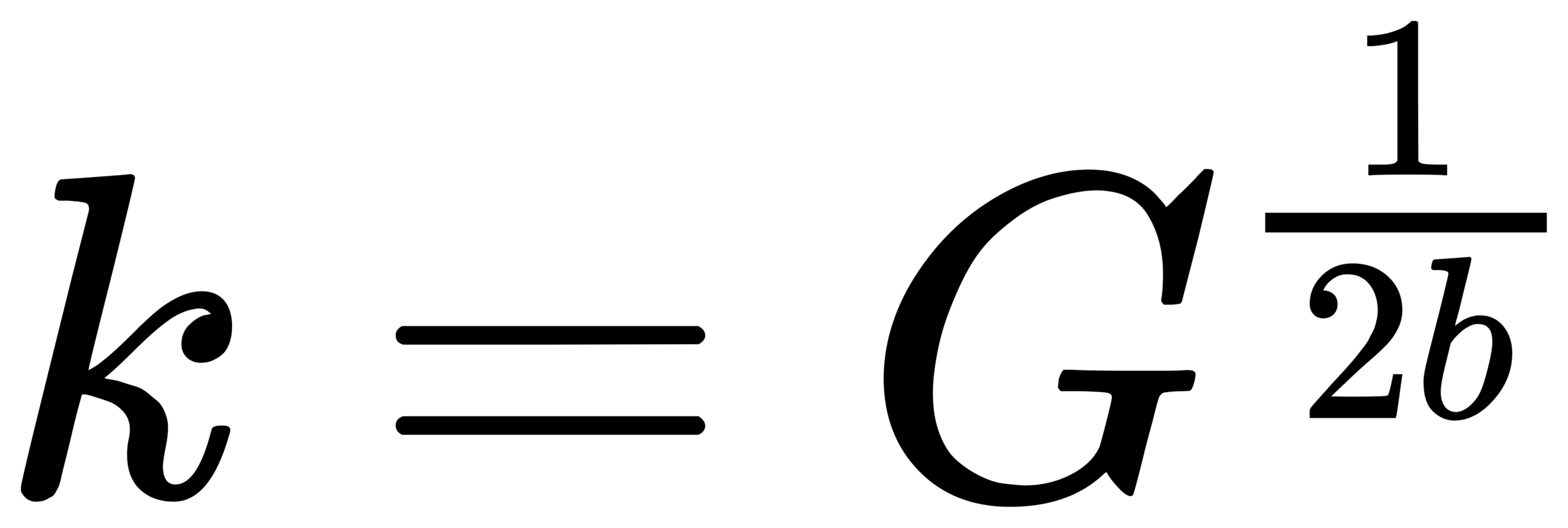

Why does the even-b case look “half-step shifted”? Intuitively, the center-frequency grid is evenly spaced on log(f). When b is even, IEC chooses a half-step offset relative to fr so that band edges align more neatly in common reporting conventions. In practice, a robust implementation is to generate the exact fm sequence using the standard’s formula, then compute edges via f1 = fm / G^(1/(2b)) and f2 = fm * G^(1/(2b)), and only then label bands by the usual nominal frequencies.

View the data with OpenTest (IEC 61260-1 Octave-Band Analysis) ->

Band edges, center frequency, and the bandwidth designator b

Standards commonly use 1/b as the “bandwidth designator”: 1/1 is one octave, 1/3 is one-third octave, etc. [1] Once (G, b, fr) are chosen, the entire band set (centers and edges) is fixed mathematically.

Exact vs nominal: why two “center frequencies” appear for the same band

“Exact” center frequencies are used for mathematically consistent definitions and filter design; “nominal” values are used for labeling and reporting. [1] ISO 266:1997 defines preferred frequencies for acoustics measurements based on ISO 3 preferred-number series (R10), referenced to 1000 Hz. [2]

As a result, the exact geometric sequence is typically labeled with familiar nominal values such as:

20, 25, 31.5, 40, 50, 63, 80, 100, 125, 160, …, 1k, 1.25k, 1.6k, 2k, 2.5k, 3.15k, …, 20k.

Implementation tip: compute edges from exact frequencies; only round/display as nominal. This avoids drifting away from the standard.

Base-10 vs base-2: why standards don’t insist on an exact 2:1 octave

Although “octave” is often thought of as 2:1, IEC 61260-1 specifies base-10 (G=10^(3/10)) rather than G=2. Key motivations include:

- Alignment with decimal preferred-number series (ISO 266 is tied to R10). [2]

- International consistency: IEC 61260-1:2014 specifies base-10 and notes that base-2 designs are less likely to remain compliant far from the reference frequency. [1]

In base-10, one-third octave corresponds to 10^(1/10) ≈ 1.258925 (also interpretable as 1/10 decade), which yields a clean mapping: 10 one-third-octave bands per decade.

“10 one-third-octave bands = 1 decade”: why this matters

With base-10 one-third-octave spacing, each step multiplies frequency by r = 10^(1/10). Therefore:

- 10 consecutive 1/3-octave bands multiply frequency by exactly 10 (one decade).

- This matches ISO 266/R10 conventions and simplifies tables, plotting, and communication.

- Standardization values readability and consistency as much as raw mathematical purity.

Figure 3: Base-10 one-third-octave spacing—10 equal ratio steps per decade (×10 in frequency)

ANSI S1.11 / ANSI/ASA S1.11: tolerance classes and a transient-signal caution

ANSI S1.11 (and later ANSI/ASA adoptions aligned with IEC 61260-1) specify performance requirements for filter sets and analyzers, including tolerance classes (often class 0/1/2 depending on edition). [3][4]

A practical caution in ANSI documents: for transient signals, different compliant implementations can produce different results. [3] This highlights that time response (group delay, ringing, averaging time constants) matters for transient analysis.

What do class/mask/effective bandwidth actually control?

“I used 1/3-octave bands” is not just about nominal band edges. Standards aim to ensure different instruments/algorithms yield comparable results by constraining:

- Frequency spacing: center-frequency sequence and edge definitions (base-10, exact/nominal, f1/f2).

- Magnitude response tolerance (mask): allowable ripple near passband and required attenuation away from center.

- Energy consistency for broadband noise: constraints on effective bandwidth so band levels are comparable across implementations.

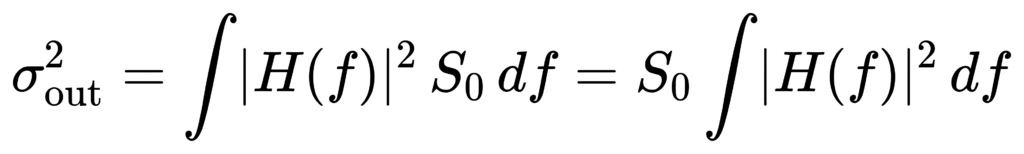

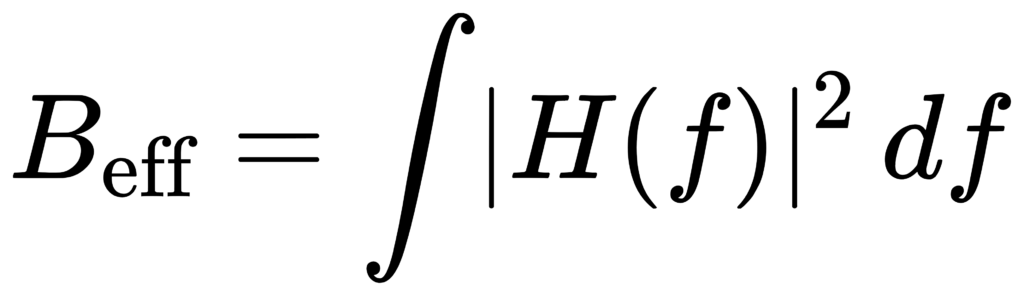

Effective bandwidth matters because real filters are not ideal brick walls. For broadband noise, the output energy depends on ∫|H(f)|^2 S(f)df. Differences in passband ripple, skirts, and roll-off can cause systematic offsets. Standards constrain effective bandwidth to keep such offsets within acceptable limits. [1][3][4]

The transient caution is not a contradiction: masks mainly constrain steady-state frequency-domain behavior, while transients depend on phase/group delay, ringing, and time averaging. [3]

Mathematics: band definitions, bandwidth, Q, and band indexing

CPB and equal spacing on a log axis

CPB is equivalent to equal-width spacing in log-frequency. If u = log(f), then every band spans a fixed Δu. Many spectra (e.g., 1/f-type) look smoother and statistically more stable in log frequency.

Band-edge formulas from the geometric-mean definition (general 1/b form)

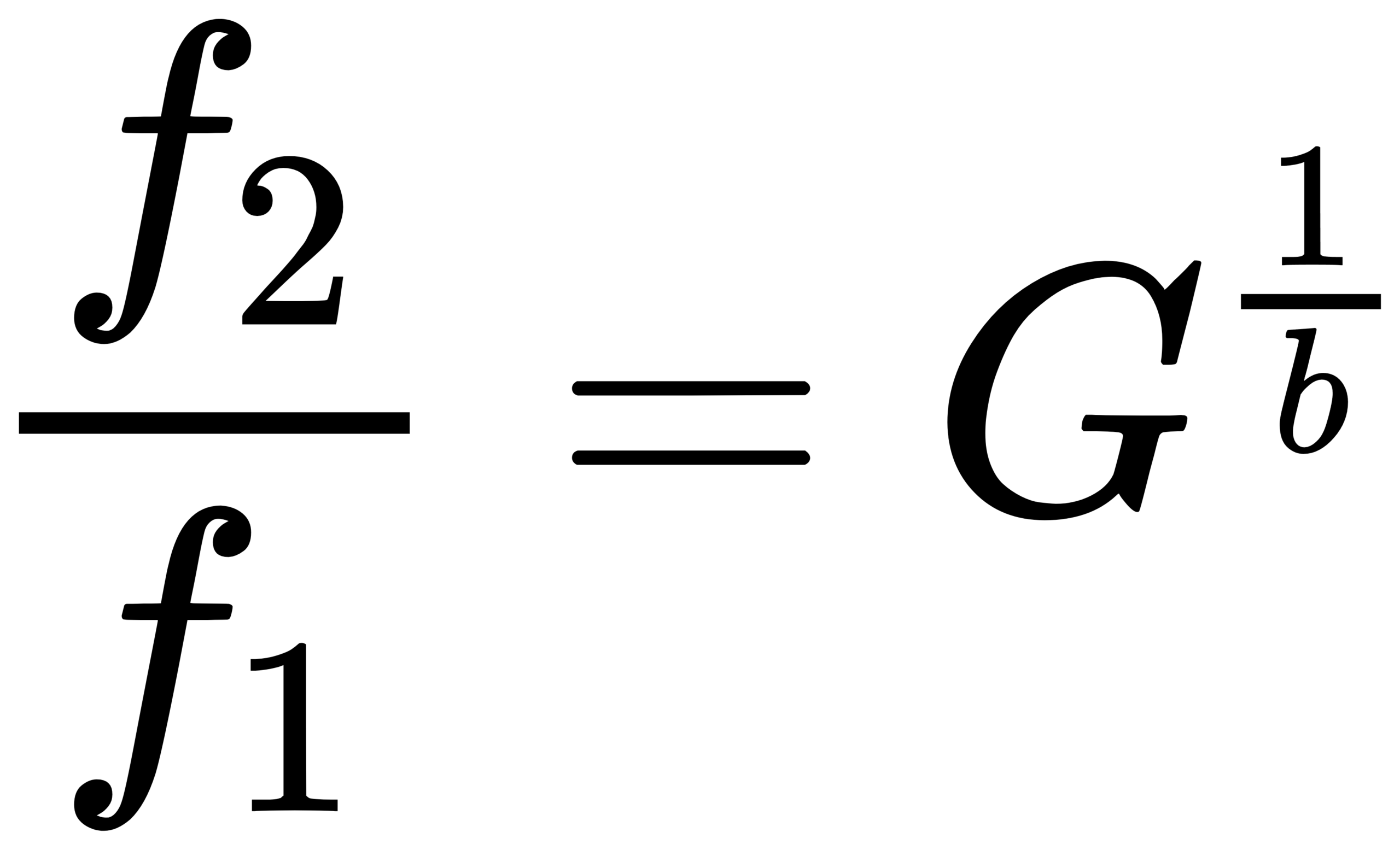

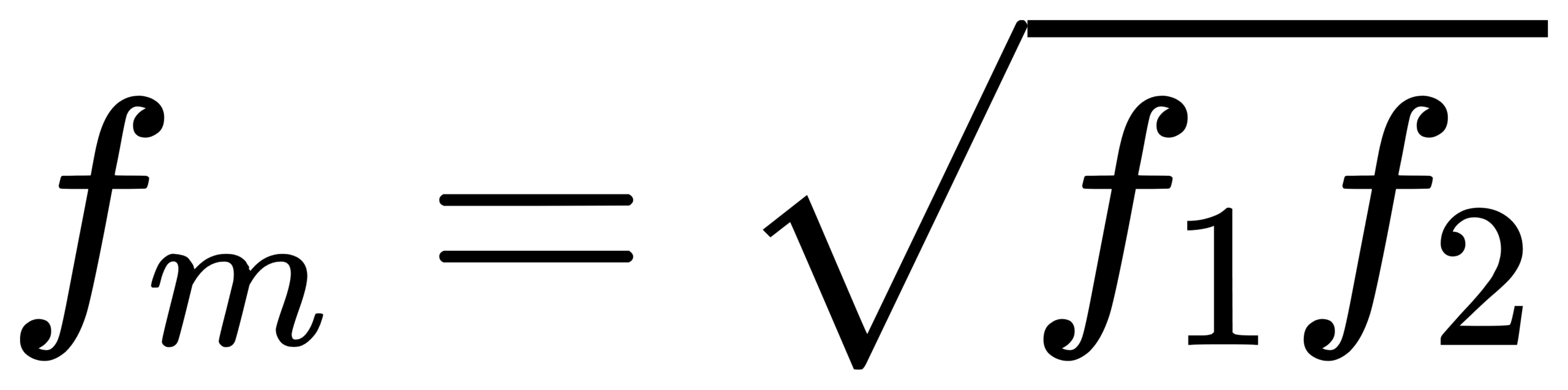

IEC defines the center frequency as the geometric mean of the edges: fm = sqrt(f1 f2). [1] For 1/b octave bands, the edge ratio is typically f2/f1 = G^(1/b), where G is the octave ratio. Then:

For base-10 one-third octave (b=3): G=10^(3/10). Adjacent center ratio is r = G^(1/3) = 10^(1/10) ≈ 1.258925; edge multiplier is k = 10^(1/20) ≈ 1.122018.

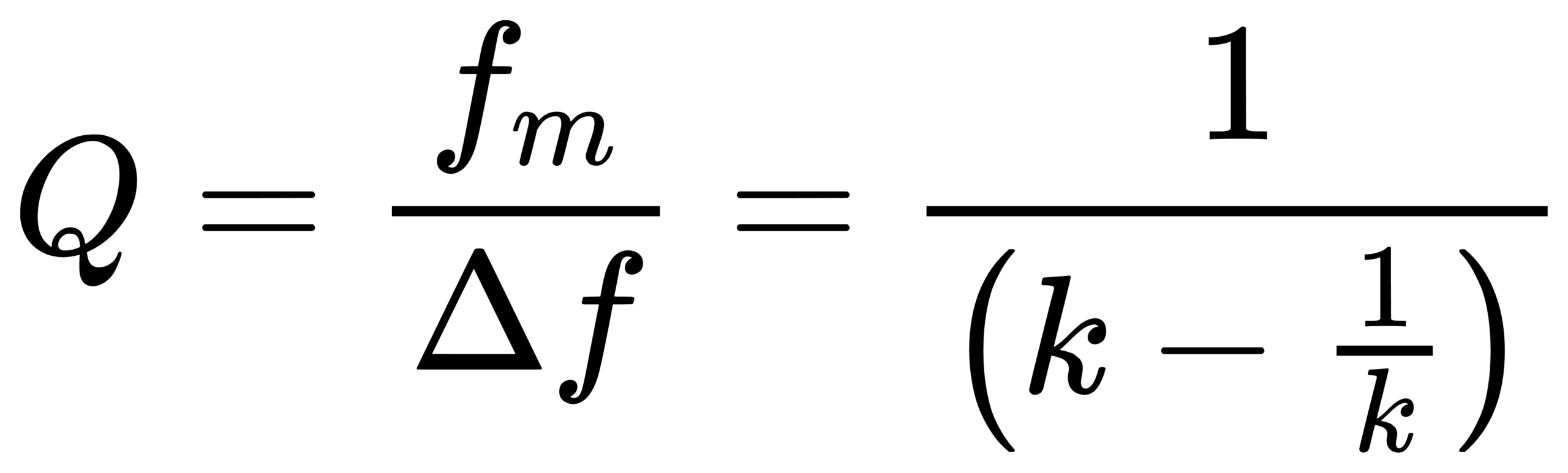

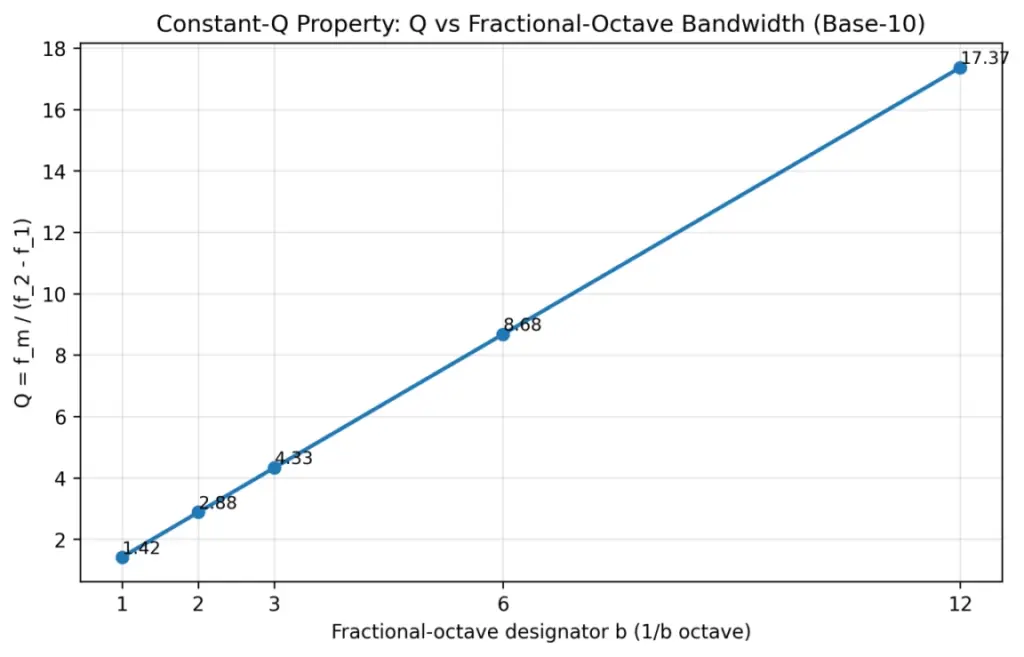

Q-factor and resolution: octave analysis is constant-Q analysis

Define Q = fm / (f2 − f1). For CPB bands, Δf = f2 − f1 scales with fm, so Q depends only on b and G (not on frequency).

Quick reference (base-10, fr=1000 Hz):

| Fractional-octave | Band ratio f2/f1 | Relative bandwidth Δf/fm | Q = fm/Δf |

| 1/1 | 1.995262 | 0.704592 | 1.419 |

| 1/2 | 1.412538 | 0.347107 | 2.881 |

| 1/3 | 1.258925 | 0.230768 | 4.333 |

| 1/6 | 1.122018 | 0.115193 | 8.681 |

| 1/12 | 1.059254 | 0.057573 | 17.369 |

Interpretation: for 1/3 octave, Q≈4.33 and each band is about 23% wide relative to its center. Finer bands (1/6, 1/12) give higher resolution but higher variance for random noise and typically require longer averaging.

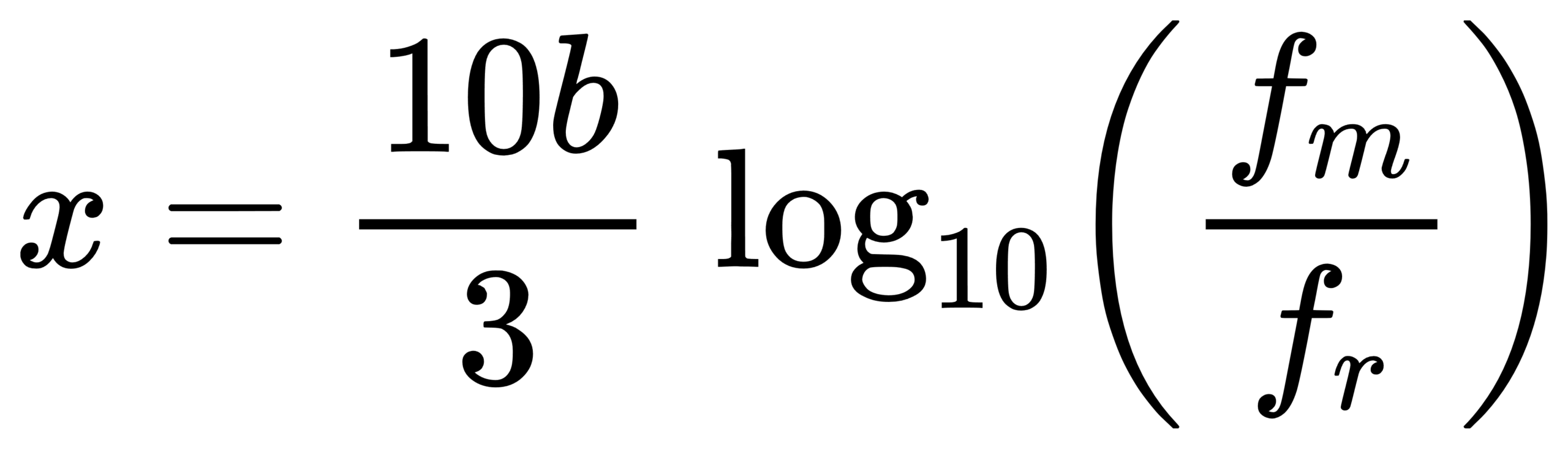

Band numbering (integer index) and formulaic enumeration

Implementations often use an integer band index x. In IEC, x appears directly in the center-frequency formula: fm = fr * G^(x/b). [1] This provides a stable way to enumerate all bands covering a target frequency range and ensures contiguous, standard-consistent edges.

For base-10:

so

and you can invert as

Figure 4: Q factor for common fractional-octave bandwidths (base-10 definition)

Two meanings of “1/3 octave”: base-2 vs base-10—do not mix them

Some literature uses base-2: adjacent centers are 2^(1/3). IEC 61260-1 and much modern acoustics practice use base-10: adjacent centers are 10^(1/10). A quick check: if nominal centers look like 1.0k → 1.25k → 1.6k → 2.0k (R10 style), it is likely base-10.

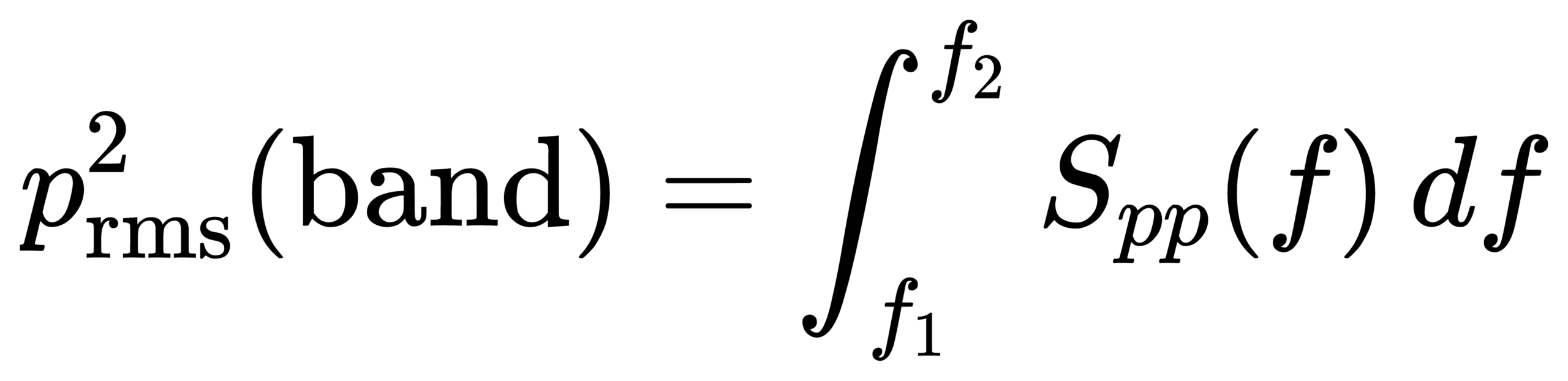

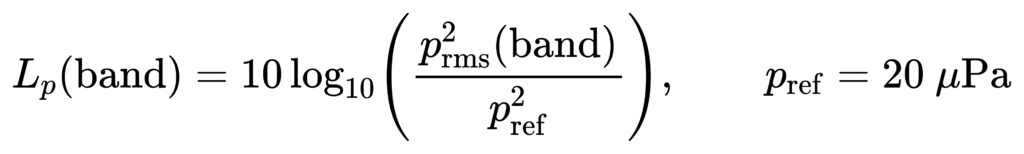

Mathematical definition of band levels: from PSD integration to dB reporting

Continuous-frequency view: integrate PSD within the band

Octave-band level is essentially the integral of power spectral density over a frequency band. For sound pressure p(t):

For vibration (velocity/acceleration), the same logic applies with different units and reference quantities.

Key point: because dB is logarithmic, any summation or averaging must be performed in the linear power/mean-square domain first.

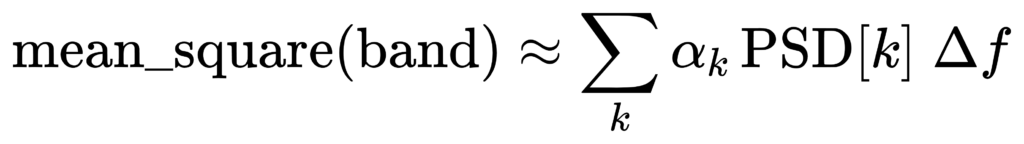

Two discrete implementations: filter-bank RMS vs FFT/PSD binning

Filter-bank method: y_b(t)=BandPass_b{x(t)}, then compute mean(y_b^2) as band mean-square (optionally with time averaging).

FFT/PSD binning method: estimate S_pp(f) (e.g., via periodogram/Welch), then numerically integrate/sum bins within [f1,f2].

For long, stationary signals, averaged results can be very close. For transients, sweeps, and short events, they often differ.

Be explicit about what spectrum you have: magnitude, power, PSD (and dB/Hz)

- Magnitude spectrum |X(f)|: amplitude units (e.g., Pa), useful for tones/harmonics.

- Power spectrum |X(f)|²: mean-square units (Pa²).

- Power spectral density (PSD): mean-square per Hz (Pa²/Hz), most common for noise.

Because octave-band levels represent band mean-square/power, you must end up integrating/summing in Pa² (or analogous) regardless of starting representation.

Frequency resolution and one-sided spectra: Δf, 0..fs/2, and the “×2” rule

FFT bin spacing is Δf = fs/N. A typical discrete approximation is:

If you use a one-sided spectrum (0..fs/2), to conserve energy you typically multiply all non-DC and non-Nyquist bins by 2 (because negative-frequency power is folded into the positive side). Different software handles these conventions differently, so align definitions before comparing results.

Window corrections: coherent gain (tones) vs ENBW (noise) are different

Windowing reduces spectral leakage but changes scaling:

- For tone amplitude: correct by coherent gain (CG), often CG = sum(w)/N.

- For broadband noise/PSD: correct by equivalent noise bandwidth (ENBW), e.g., ENBW = fs·sum(w²)/(sum(w))². [9]

CG controls peak amplitude; ENBW controls average noise-floor area. Octave-band levels are energy statistics and are more sensitive to ENBW.

| Window | Coherent Gain (CG) | ENBW (bins) |

| Rectangular | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Hann | 0.500 | 1.500 |

| Hamming | 0.540 | 1.363 |

| Blackman | 0.420 | 1.727 |

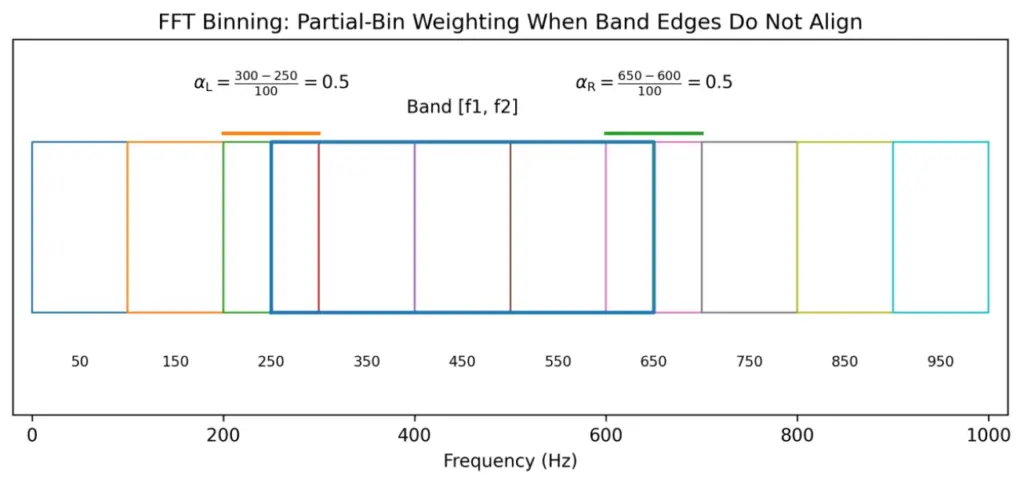

Partial-bin weighting: what to do when band edges do not align to FFT bins

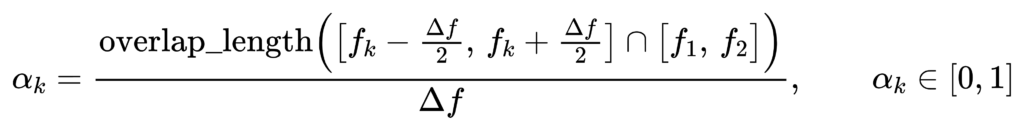

Band edges rarely land exactly on bin frequencies. Treat PSD as approximately constant within each bin of width Δf, and weight boundary bins by their overlap fraction:

This produces smoother, more physically consistent band levels when N or band edges change.

Figure 5: Partial-bin weighting schematic when band edges do not align with FFT bins

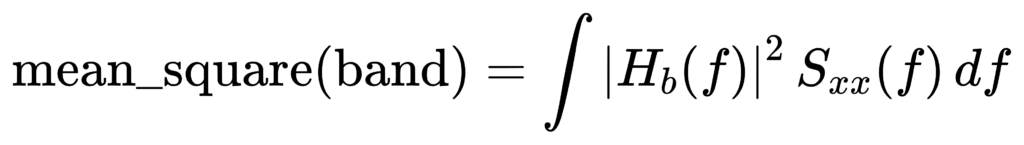

A unifying formula: both methods compute ∫|H_b(f)|² S_xx(f) df

Both filter-bank and PSD binning can be written as:

Brick-wall binning corresponds to |H_b|² being 1 inside [f1,f2] and 0 outside. A true standards-compliant filter has a roll-off and ripple, which is why standards constrain masks and effective bandwidth.

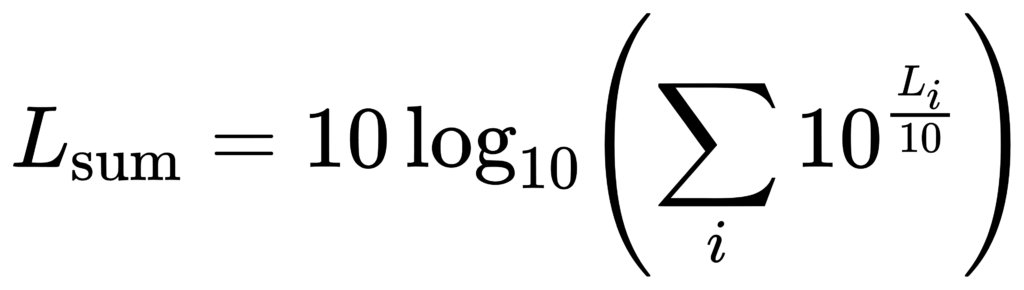

Band aggregation: composing 1-octave from 1/3-octave, and forming total levels

Under ideal partitioning and energy accounting:

- Three adjacent 1/3-octave bands can be combined to approximate one full octave band.

- Summing all band energies over a covered range yields the total energy.

Always combine in the energy domain.

If L_i are band levels in dB, energies are E_i = 10^(L_i/10). Then:

IEC 61260-1 notes that fractional-octave results can be combined to form wider-band levels. [1]

Effective bandwidth: why standards specify it

Real filters are not ideal rectangles. For white noise (constant PSD S0), output mean-square is:

For non-white spectra such as pink noise (PSD ~ 1/f), standards may define normalized effective bandwidth with weighting to maintain comparability across typical engineering noise spectra. [1]

Practical implication: FFT “hard-binning” implicitly assumes a brick-wall filter with B_eff = (f2 − f1). A compliant octave filter has skirts, so B_eff can differ slightly (and by class). To match results, either approximate the standard’s |H(f)|² in the frequency domain or document the methodological difference.

Why 1/3 octave is favored (math + perception + engineering trade-offs)

Information density is “just right”: finer than 1 octave, steadier than very fine fractions

A single octave band can be too coarse and hide spectral shape; very fine fractions (e.g., 1/12, 1/24) can be unstable and expensive:

- Higher estimator variance for random noise (each band captures less energy).

- More computation and higher reporting burden.

- Often more detail than regulations or rating schemes need.

One-third octave is the classic compromise: enough resolution for engineering insight, stable enough for standardized measurements, and broadly supported by instruments and software.

Psychoacoustics: critical bands in mid-frequencies are close to 1/3 octave

Many psychoacoustics references describe ~24 critical bands across the audible range, and in the mid-frequency region the critical-bandwidth is often similar to a 1/3-octave bandwidth. [7][8] This makes 1/3 octave a natural intermediate representation for problems tied to perceived sound, while still being more standardized than Bark/ERB scales.

Direct standards/application pull: many workflows mandate 1/3 octave I/O

Once major standards define inputs/outputs in 1/3 octave, ecosystems (instruments, software, reporting templates) converge around it. Examples:

- Building acoustics ratings: ISO 717-1 references one-third-octave bands for single-number quantity calculations. [5]

- Room acoustics parameters (e.g., reverberation time) are commonly reported in octave/one-third-octave bands (ISO 3382 series). [6]

Extra base-10 benefits: R10 tables, 10 bands/decade, readability

- 10 bands per decade: multiplying frequency by 10 corresponds to exactly 10 one-third-octave steps (very clean for log plots).

- R10 preferred numbers: 1.00, 1.25, 1.60, 2.00, 2.50, 3.15, 4.00, 5.00, 6.30, 8.00 (×10^n) are widely recognized and easy to communicate.

- Compared with base-2, decimal labeling is less awkward and cross-standard ambiguity is reduced.

Octave-band analysis is typically implemented using either FFT binning or a filter bank. Keep reading -> Octave-Band Analysis Guide: FFT Binning vs. Filter Bank

OpenTest integrates both methods. Download and get started now -> or fill out the form below ↓ to schedule a live demo.

Explore more features and application stories at www.opentest.com.

References

[1] IEC 61260-1:2014 PDF sample (iTeh): https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/13383/3c4ae3e762b540cc8111744cb8f0ae8e/IEC-61260-1-2014.pdf

[2] ISO 266:1997, Acoustics - Preferred frequencies (ISO): https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/

[3] ANSI S1.11-2004 preview PDF (ASA/ANSI): https://webstore.ansi.org/preview-pages/ASA/preview_ANSI%2BS1.11-2004.pdf

[4] ANSI/ASA S1.11-2014/Part 1 / IEC 61260-1:2014 preview: https://webstore.ansi.org/preview-pages/ASA/preview_ANSI%2BASA%2BS1.11-2014%2BPart%2B1%2BIEC%2B61260-1-2014%2B%28R2019%29.pdf

[5] ISO 717-1:2020 abstract (mentions one-third-octave usage): https://www.iso.org/standard/77435.html

[6] ISO 3382-2:2008 abstract (room acoustics parameters): https://www.iso.org/standard/36201.html

[7] Ansys Help: Bark scale and critical bands (mentions midrange close to third octave): https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public/Views/Secured/corp/v252/en/Sound_SAS_UG/Sound/UG_SAS/bark_scale_and_critical_bands_179506.html

[8] Simon Fraser University Sonic Studio Handbook: Critical Band and Critical Bandwidth: https://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio-webdav/cmns/Handbook5/handbook/Critical_Band.html

[9] MathWorks: ENBW definition example: https://www.mathworks.com/help/signal/ref/enbw.html

Related Products

OpenTest

SonoDAQ Pro

Get in touch

If you are interested or have questions about our products, book a demo and we will be glad to show how it works, which solutions it can take part of and discuss how it might fit your needs and organization.