Measure Sound Better

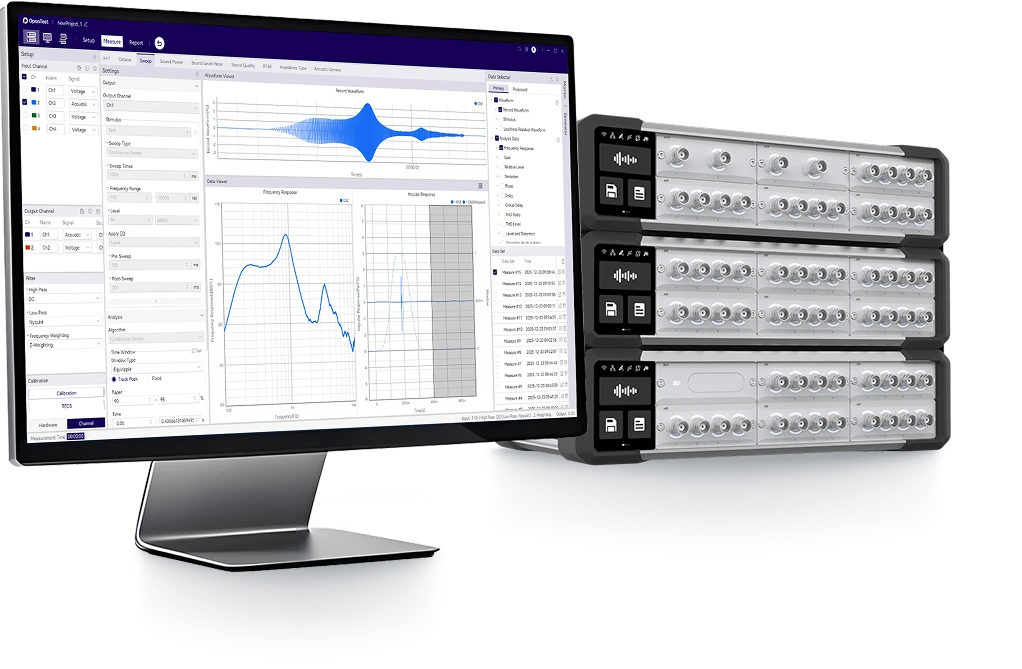

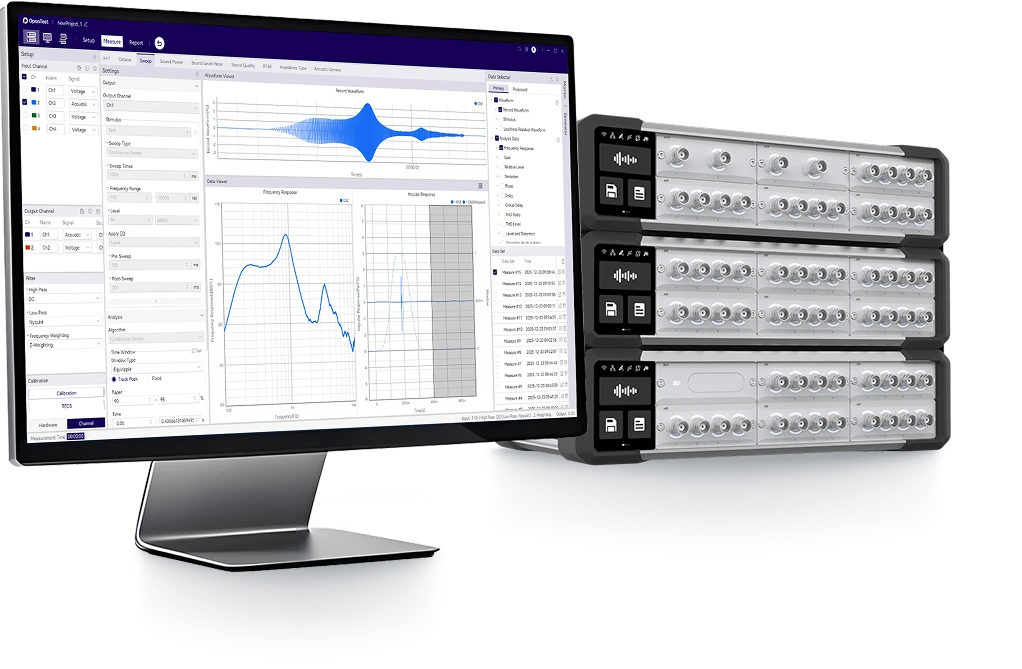

SonoDAQ

Next-Generation Sound & Vibration DAQ

- PTP/GPS Precision Sync for Distributed Acquisition

- Built-in 6 TOPS NPU for Local Edge AI Processing

- Modular, Scalable Design to Expand Channels and Functions

- 1000V High Isolation

- Ideal for NVH and Audio Measurement Tests

NEW

OpenTest

Open-Source, Cross-Platform Audio & NVH

Test & Measurement Software

- Open Hardware

- Open Plugin

NEW

CRY3213 NVH Measurement Microphone

- IP67

- Robust Shock & Vibration Resistance

- Extreme Temp. Range: -50°C to 125°C

- Free-Field

- Frequency Range:3.15 Hz-20 kHz

NEW

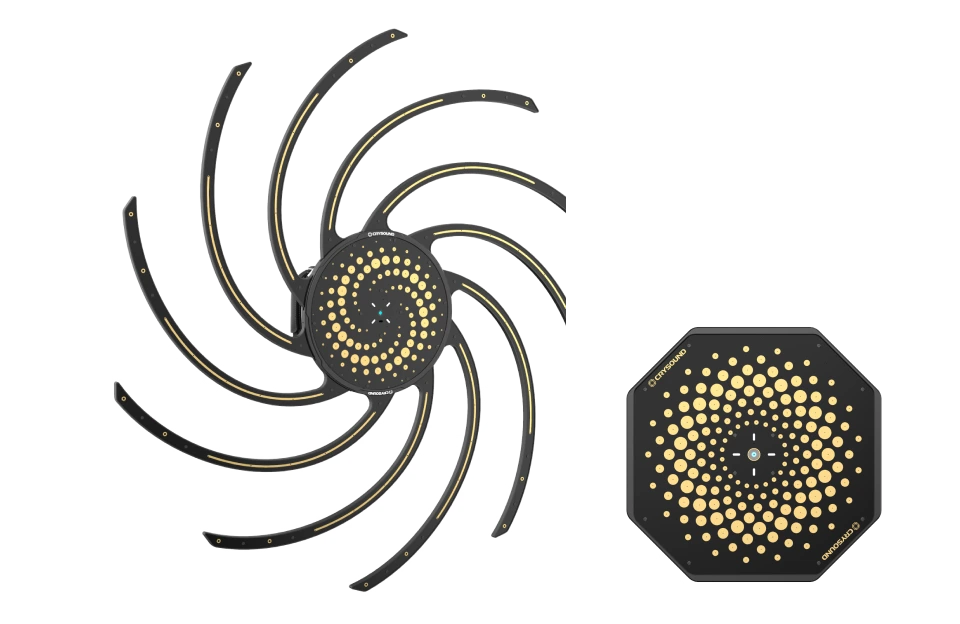

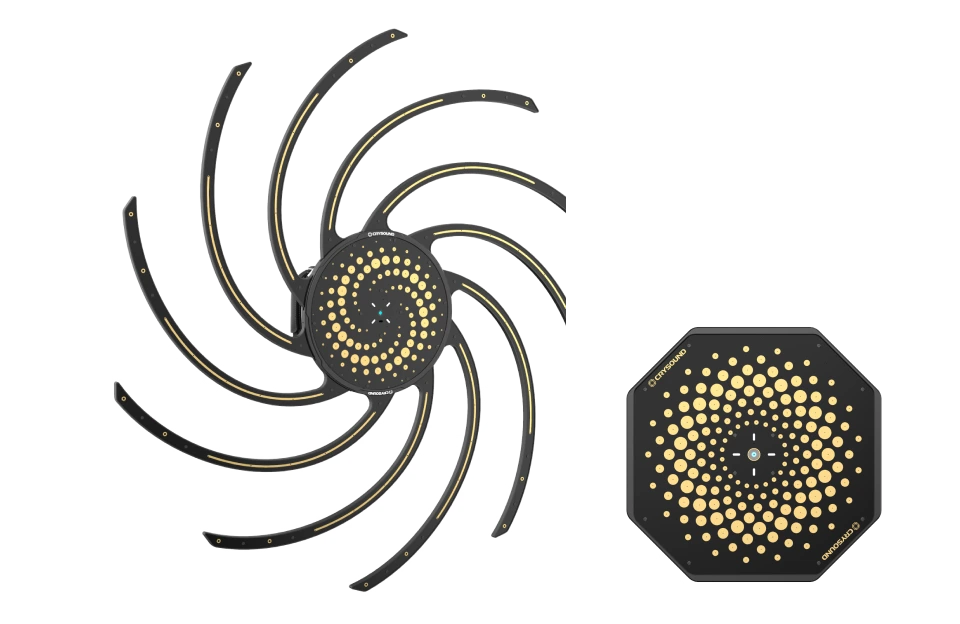

CRY8500 Series SonoCam Pi Acoustic Camera

- Array Size Selectable at 30 / 70 / 110 cm

- 208-Channel Synchronous Data Acquisition and Wave Data Output

- Open API Supporting Customizable Algorithm Development

- Ideal for University Research, UAV Detection and NVH Testing

- All-in-One Acoustic Imaging Platform with Array & 8-Inch Display

NEW

CRY580 A²B Interface

- Single-Master Multi-Slave Topology with Daisy Chain Support

- Multi-Channel I²S/TDM Audio Interfaces

- Ensures Synchronous Sampling and Data Transmission

- Supports PDM Interfaces, with Up to 4 PDM Mic Inputs

NEW

Products

Featured Products

Product Lines

Deliver reliable products for acoustic measurement and testing

Sensors

Provides measurement microphones, mouth simulators, ear simulators, and more for accurate acoustic measurements.

Data Acquisition

Combines hardware and software for high-speed, high-precision signal acquisition, ideal for various acoustic applications.

Acoustic Imaging

Offers acoustic cameras for gas leak detection, partial discharge, and fault diagnostics across handheld, fixed, and UAV platforms.

Noise Measurement

Includes sound level meters, noise sensors, and monitoring systems for effective noise measurement and analysis.

Electroacoustic Test

Delivers complete electroacoustic testing solutions, including analyzers, testing software, and acoustic test boxes.

Solutions

Provide high-quality solutions for the acoustic field

Blogs

Share insights, cases and trends in acoustic testing

Sound is everywhere in our daily life: birdsong, street noise, engine roar, even the faint airflow from an air conditioner. For people, sound is not only about whether we can hear it, but whether it feels comfortable, is disturbing, or poses a risk. The same 70 dB can feel completely different; and when something feels "noisy", the cause may come from the source itself, the propagation direction, or reflections from the environment. When we turn this "perception" into quantifiable engineering data, the three most easily confused concepts are sound pressure, sound intensity, and sound power. They answer: Sound pressure: how loud it is at a specific point; Sound intensity: how much sound energy is propagating in a particular direction; Sound power: how loud the source is in terms of its total acoustic emission; This article explains sound pressure, sound intensity, and sound power in an intuitive way, so you can better understand sound. Sound Waves In engineering acoustics, sound pressure, sound intensity, and sound power are three fundamental and important physical quantities. Before introducing them in detail, we need the concept of a sound wave. A vibrating source sets the surrounding air particles into vibration. The particles move away from their equilibrium position, drive adjacent particles, and those adjacent particles generate a restoring force that pushes the particles back toward equilibrium. This near-to-far propagation of particle motion through the medium is what we call a sound wave. Figure 1. Propagation of a Sound Wave in Air Sound Pressure When there is no sound wave in space, the atmospheric pressure is the static pressure p0. When a sound wave is present, a pressure fluctuation is superimposed on p0, producing a pressure fluctuation p1. Here p1 is the sound pressure (unit: Pa). Therefore, sound pressure is the instantaneous deviation of the air static pressure caused by the sound wave. The human brain does not respond to the instantaneous amplitude of sound pressure, but it does respond to the root-mean-square (RMS) value of a time-varying pressure. Therefore, the sound pressure p can be expressed as: In practical engineering applications, the sound pressure level Lp: where Pref = 2 × 10-5 Pa is the reference sound pressure. In practice, we usually use sound pressure level (dB) to characterize sound pressure, rather than using pressure in pascals. Why? Figure 2 answers this well. From a library to the entrance of a high-speed rail station, sound pressure may increase by a factor of 100, while sound pressure level increases by only 40 dB. This reflects the difference between a linear scale and a logarithmic scale. From an engineering perspective, using sound pressure directly leads to large numeric variations that are inconvenient for evaluation. Moreover, the human auditory system is closer to a logarithmic response, so sound pressure level better matches hearing. Figure 2. Sound Pressure and Sound Pressure Level Sound Intensity Sound intensity describes the transfer of acoustic energy. It is the acoustic power passing through a unit area per unit time. It is a vector quantity that is directional, with units of W/m2, defined as the time average of the product of sound pressure and particle velocity: where v(t) denotes the particle velocity vector. Under the ideal plane progressive-wave approximation, sound pressure and particle velocity approximately satisfy: where ρ is the air density, c is the speed of sound. Therefore, the magnitude of sound intensity along the propagation direction can be written as: Similarly, sound intensity has a corresponding intensity level LI: where I0 = 10-12 W/m2 is the reference sound intensity. Compared with sound pressure level measurements, sound intensity measurements have the following characteristics: Directional:it can distinguish whether acoustic energy is propagating outward or flowing back, so under typical field conditions it is often less sensitive to reflections and background noise; Source localization:intensity scanning can directly reveal the main radiation regions and leakage points, making remediation more targeted; Higher system complexity:it typically requires an intensity probe, with higher overall cost and more setup and calibration effort; Figure 3. Sound Intensity Testing A key advantage of sound intensity measurement in engineering applications is that it characterizes both the direction and magnitude of acoustic energy flow. It can separate the contributions of outward radiation from the source and reflected backflow from the environment, so under non-ideal field conditions it tends to be less affected by reflections and background noise. In addition, the sound intensity method can obtain sound power directly by spatially integrating the normal component of intensity over an enclosing surface. Combined with surface scanning, it can identify dominant source regions and locate leakage points. Therefore, it is highly practical and interpretable for noise diagnosis, verification of noise-control measures, and sound power evaluation. The key instrument for sound intensity testing is the sound intensity probe. Unlike a single microphone, an intensity probe is not used merely to measure “how large the pressure is”; it must provide the basic quantities required for calculating intensity (sound pressure and particle velocity). Therefore, the probe typically outputs two synchronous channels and, together with a two-channel data-acquisition front end and dedicated algorithms, yields intensity results. In engineering practice, the probe often includes interchangeable spacers, positioning fixtures, and windshields. Channel amplitude/phase matching, phase calibration capability, and airflow-interference mitigation directly determine the credibility and usable frequency range of intensity measurements. Two types of sound intensity probes are commonly used: P-U probes (pressure-particle-velocity) and P-P probes (pressure-pressure). A P-U probe consists of a microphone and a velocity sensor, measuring sound pressure p(t) and particle velocity v(t) simultaneously. The principle is more direct, but particle-velocity sensors are often more sensitive to airflow, contamination, and environmental conditions, requiring more protection and maintenance in the field and usually costing more. Figure 4. P-U Sound Intensity Probe (Microflown) A P-P probe uses two matched microphones aligned on the same axis. It uses the two pressure signals p1(t) and p2(t) to estimate the particle-velocity component v(t). However, it is sensitive to inter-channel phase matching and the choice of microphone spacing - the spacing determines the effective frequency range: a larger spacing benefits low frequencies, but high frequencies suffer from spatial sampling error; a smaller spacing benefits high frequencies, but low frequencies become more susceptible to phase mismatch and noise. Figure 5. P-P Sound Intensity Probe (GRAS) P-U probes are relatively niche, mainly because it is difficult to make them both stable and inexpensive, and they generally have poorer resistance to airflow. P-P probes, thanks to their good field robustness and the ability to adjust bandwidth flexibly via microphone spacing, are currently the mainstream choice in engineering applications. Sound Power Sound power W is the rate at which a source radiates acoustic energy, with units of watts (W). For any closed measurement surface S enclosing the source, the sound power equals the integral of the normal component of sound intensity over that surface: where n is the unit normal vector pointing outward from the measurement surface. Sound power level Lw is defined as: where W0 = 10-12 W is the reference sound power. Figure 6. Sound Power Measurement Sound power characterizes a source's inherent acoustic emission capability: the total acoustic energy it radiates per unit time. It has little to do with measurement distance or microphone position, and ideally does not depend on how "loud" it is at a particular point in a room. This is fundamentally different from sound pressure and sound intensity. To better understand sound pressure, sound intensity, and sound power, you can imagine noise as water flow. Sound pressure is like the "water pressure" you feel when you put your hand at a certain location (it changes with distance to the nozzle, direction, and the shape of the basin). Sound intensity is like the instantaneous "direction and rate of flow" (it has direction and can even be reflected by walls, creating backflow). Sound power is like "how much water the nozzle sprays per second" - it is a property of the nozzle itself. In measurement, it is obtained by integrating the outward normal flow over a surface surrounding the device. Figure 7. Analogy of Sound Pressure, Sound Intensity, and Sound Power In real projects, the algorithms for sound pressure, sound intensity, and sound power are relatively mature. The hardest part is acquiring the signals accurately and obtaining results quickly. In particular, tasks such as multi-channel microphone arrays, sound intensity, and sound power impose three hard requirements on the data-acquisition front end: low noise and wide dynamic range, strict synchronization and phase consistency, and stable on-site connections and power. SonoDAQ + OpenTest is positioned to provide a "front-end acquisition + synchronous analysis" foundation for engineering acoustics, allowing engineers to focus more on operating-condition control and data interpretation. It delivers the most value in the following types of projects: Sound intensity diagnostics: dual-channel synchronous sampling plus better amplitude/phase consistency management provide a more stable data basis for P-P intensity probes and intensity scanning. Microphone array systems: better aligned with engineering deployment needs in channel scalability, synchronization, and cabling, making it suitable for building expandable distributed test platforms. Sound power and standardized testing: helps engineers quickly lay out measurement points, covering multiple international sound power test standards. With guided configuration, one-click testing, and automatic report export, it saves substantial time and effort for engineers. Figure 8. SonoDAQ + OpenTest To see more clearly how SonoDAQ is connected and configured, typical application cases (such as equipment noise evaluation, sound source localization, and sound power testing), and commonly used BOM lists, please fill in the form below, and we will recommend the best solution to address your needs.

Valves are the "core control components" of pipeline systems. They perform four key functions—opening/closing, regulating, isolating, and directing—enabling precise control of fluid flow. Once sealing integrity fails, minor cases can lead to process upsets and energy losses, while severe cases may result in fires or explosions, toxic exposure, or environmental pollution. We built a valve leak application around the three things customers care about most on site—fewer missed detections and false alarms, better localization, and more reliable leak-rate estimation—by distilling them into an executable, traceable standardized workflow and closing the loop in the application for end-to-end deployment. Common Causes of Valve Internal Leakage What leads to valve leakage? We summarize it into the following four main causes: Normal wear and tear: Frequent opening and closing gradually wears the sealing surfaces; long-term scouring and erosion from the flowing medium can also degrade the seal fit. Process medium factors: Sulfur compounds and similar components in the medium can cause electrochemical corrosion; residual construction contaminants—such as sand, grit, and particles—can accelerate wear and scratch the sealing surfaces, leading to poor sealing. Improper operation and maintenance: Using an on/off valve for throttling, lack of routine cleaning and preventive maintenance, inadequate servicing, or improper/unsafe operation can all damage sealing surfaces or prevent full closure. Installation and management issues: Outdoor storage exposed to rain, ingress of mud and sand, and sandblasting/field conditions introducing grit or debris into the valve cavity can contaminate and scratch sealing surfaces, ultimately causing internal leakage. Figure 1. Illustration of Valve Internal Leakage When a valve is closed but the sealing surfaces do not fully mate, the pressure differential drives the medium to pass through small gaps from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side, forming high-velocity micro-jets and turbulent flow. This leakage typically results in several observable signs, including sound/ultrasound, vibration, abnormal pressure behavior, and temperature anomalies or frosting. Figure 2. Symptoms of Valve Leakage Why Contact Ultrasound Works When a valve seal fails, high-pressure fluid passing through tiny gaps at the sealing surfaces generates turbulent flow, producing high-frequency ultrasonic signals in the 20–100 kHz range. The signal intensity is generally positively correlated with the leak rate—the larger the leak, the higher the amplitude. In the field, you can capture ultrasonic signals at measurement points upstream of the valve, on the valve body, and downstream, then apply algorithms to extract and analyze signal features to detect and localize internal leakage. Compared with traditional methods, temperature-based approaches are easily affected by heat conduction and are difficult to quantify; pressure-hold tests are time-consuming and poor at pinpointing the leak location; and listening by ear is inefficient, prone to missed detections and false alarms, and heavily dependent on individual experience. That's exactly why we launched this application—turning an experience-driven task into a standardized, process-driven workflow, supported by acoustics and data analytics. Figure 3. CRY8124 Acoustic Imaging Camera with IA3104 Contact Ultrasound Sensor Workflow and Key Capabilities More standardized workflow: turning on-site operation into guided testing In the CRY8124 valve leak application, the software features a standardized and visualized workflow. Operators follow on-screen prompts to place the contact ultrasound sensor on each measurement point in sequence and simply tap "Test". The results are displayed on the interface, and the algorithm automatically determines whether internal leakage is present after the test. Figure 4. Valve Leakage Detection Feature Page At the same time, the software provides standardized inputs for key parameters such as valve ID, valve type, valve size, medium type, and the upstream/downstream pressure differential. This means test results are easier to align across the same unit, different shifts, and different operators—making retesting and trend management much more consistent. Figure 5. Valve Leakage Detection Feature Page Smarter: automatic diagnosis + leak-rate estimation Our valve leak detection capability focuses on two key improvements: By analyzing the dB level at each measurement point and the features of the ultrasonic signal, the system automatically determines the internal leakage result based on algorithmic data, reducing reliance on manual interpretation. Built-in AI algorithms estimate the leak rate from ultrasonic features at the measurement points, providing a quantitative reference to support valve maintenance decisions. This is the core logic behind our emphasis on a "higher detection rate": when judgments rely less on subjective experience, missed detections and false alarms become far more controllable—especially in complex sites with many valves and multiple parallel branches. Application Scenarios Across different industries, there is a common need for valve leak detection: Figure 6: Application Scenarios Field Case Study Case : A Coal-to-Chemicals Plant in Inner Mongolia (Fuel Gas / Coal Gas System) Below is a real field test case of valve leak at a coal-chemical plant. Any internal leakage in fuel gas or coal gas systems can compromise isolation. If leakage exists, the downstream side may remain gas-charged, and the work area may still be exposed to risks of CO and sulfur-containing acid gases entering the zone—potentially leading to poisoning, fire, or even explosion hazards. Using contact ultrasonics, we performed on-site testing on the suspected valves, quickly identified the leakage points, and estimated the leak rate. This helped the customer turn "isolation confirmed" from an experience-based judgment into data-backed verification, prioritize corrective actions, reduce work risks caused by misjudged isolation, and ensure safer maintenance and stable operation. Figure 7. On-site Test Photos Valve type: Fuel gas compressor room bypass valve (butterfly valve). Test result: 19.8 L/min. Medium / pressure: Fuel gas (H₂, CO, CH₄), 3 MPa. Figure 8. Test Results Valve type: Fuel gas compressor room plug valve Test result: 1.7 L/min. Medium / pressure: Coal gas (mainly CO), 2.5 MPa. Figure 9. Test Results On-Site Test Method: Repeatable 5-Point Measurements Confirm Operating Conditions Ensure there is a pressure differential, and isolate interfering branches as much as possible. Key steps Close the valve to be tested. Open the upstream and downstream valves of the test section. Confirm a pressure differential between upstream and downstream gauges, and verify ΔP > 0.1 MPa. As shown in the figure below When testing Valve A for valve leakage: open Valves B and C, and close Valves A and D. When testing Valve B for valve leakage: open Valves A and C, and close Valves B and D. Figure 10. Valve Status Place Measurement Points (MP1–MP5) Cover upstream → valve core → downstream. MP3: Located at the valve core. MP2: Located 1–2 pipe diameters (D) upstream of the valve (place the point on the pipe wall away from the valve). MP1: Located upstream of the valve, 2–3D away from MP2. If space is limited, MP1–MP2 spacing can be shortened to 0.5D. MP4: Located 1D downstream of the valve (place the point on the pipe wall away from the valve). MP5: Located downstream of the valve, 1–2D away from MP4 (recommended on the pipe wall just after the valve flange). If space is limited, MP5–MP4 spacing can be shortened to 0.5D. D = pipe diameter Figure 11. Test Point Layout NoteFor small, flangeless threaded valves, the spacing between measurement points should be at least three pipe diameters (3D). Fugure12. Test Point Layout FAQ We've listed some common scenario-based questions about valve internal leakage to help you understand the application faster and choose the right solution more efficiently. Q1. How do I choose a Contact Ultrasound Sensor for pipelines at different temperatures? A1. We recommend the following sensor selection based on pipe surface temperature: For low-temperature pipes (below -20°C) or high-temperature pipes (above 50°C), use a needle-type Contact Ultrasound Sensor. For temperatures between -20°C and 50°C, use a ceramic Contact Ultrasound Sensor for signal capture. Q2. Which valves can be tested for valve leakage? A2. This method is suitable for valve leakage detection across a wide range of valve types, including: Gate valves Plug valves Globe valves Ball valves Check valves Butterfly valves Needle valves Pressure relief valves Pinch valves If your valve type is not listed above, please feel free to contact us. Q3. Can we still test if the valve and pipe are insulated? A3. If the insulation fully covers the valve and pipeline, testing may not be possible. You'll need to remove the insulation at the measurement area, or leave an opening of about 7 cm in diameter so the Contact Ultrasound Sensor can directly contact the pipe wall to capture the signal. Q4. What should we pay attention to regarding the pipe surface during data collection? A4. The Contact Ultrasound Sensor must make good contact with a solid surface to reliably capture ultrasonic signals propagating through the pipe. Large particles or debris between the sensor and the pipe surface can lead to inaccurate results. If the pipe wall is rusty, wipe off any large dust or loose particles on the surface before testing. Contact Us If you'd like to learn more about how CRYSOUND acoustics can be applied to valve leak detection, or if you want a more suitable inspection solution based on your on-site process conditions and acceptance criteria, please contact us via the form below. Our engineers will get in touch with you.

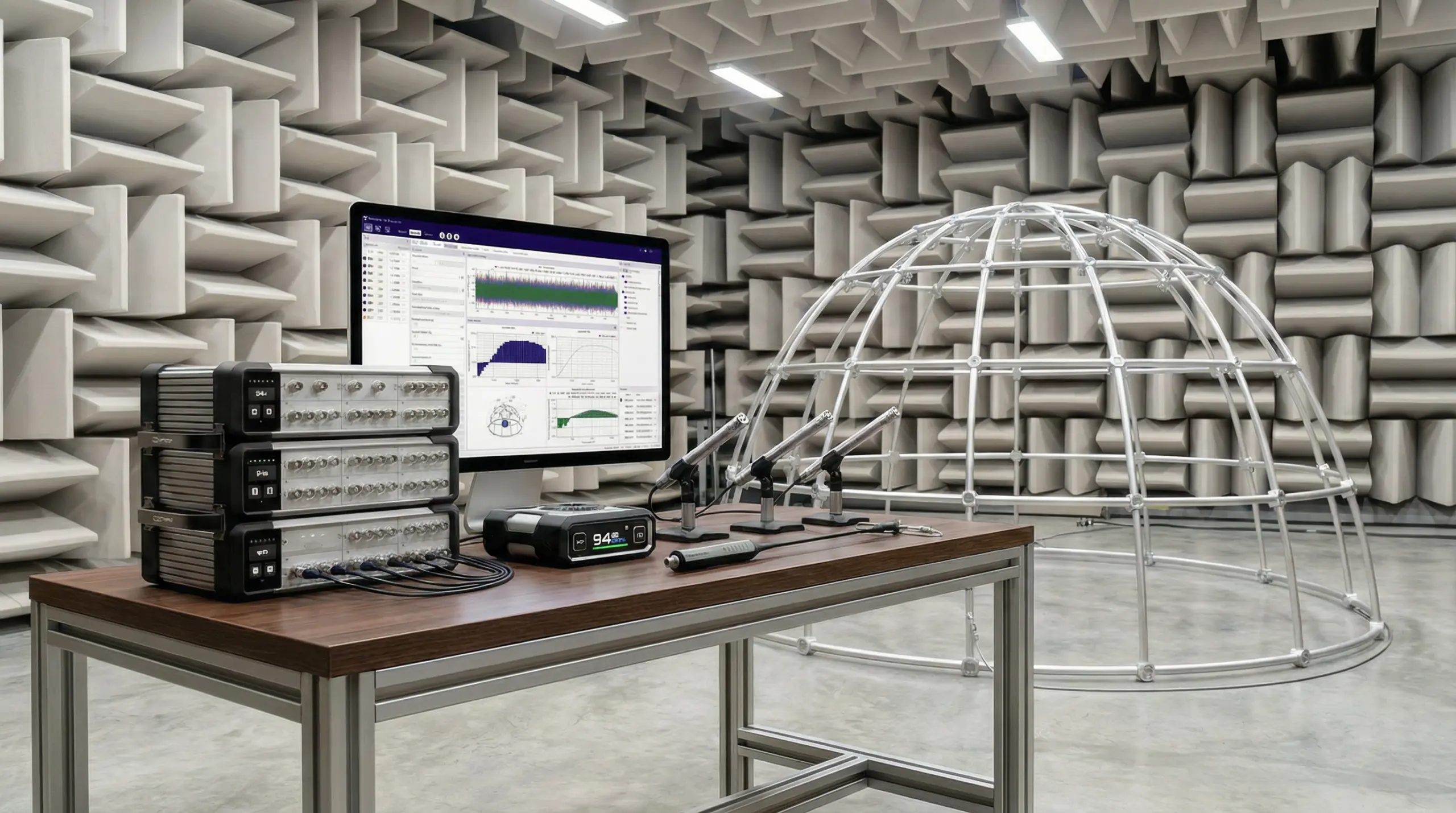

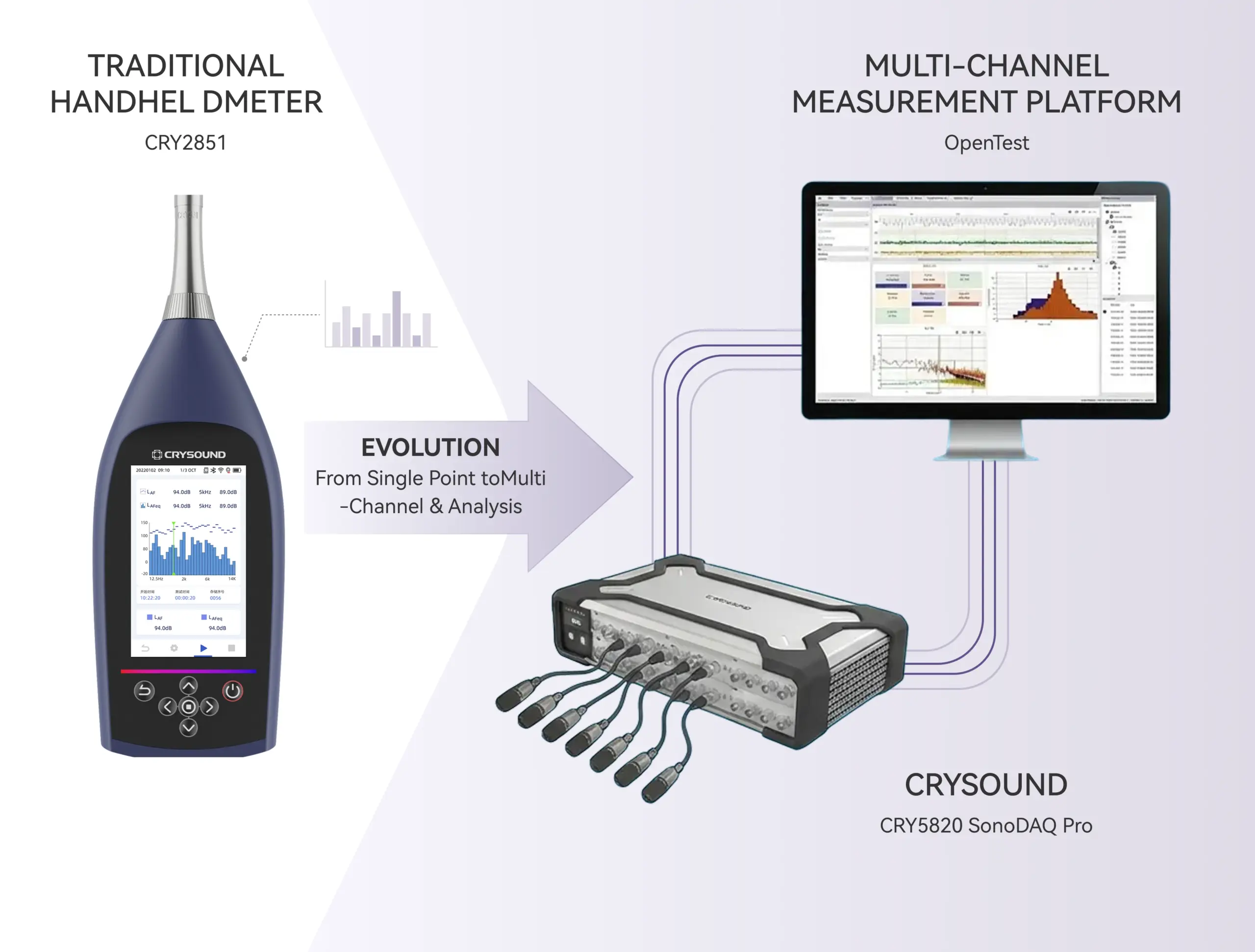

This article introduces how to build a multi-channel sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672-1 using OpenTest, in combination with SonoDAQ data acquisition hardware and measurement-grade microphones. The system supports A / C / Z frequency weighting, F / S / I time weighting, and standard acoustic quantities such as Lp, Leq, and Ln, making it suitable for a wide range of applications including environmental noise, product noise, and automotive NVH testing. From Handheld Sound Level Meters to Multi-Channel Sound Level Measurement Platforms In acoustics and vibration testing, one fundamental question appears in almost every project: “How loud is it?” From office equipment and household appliances to automotive NVH and industrial machinery, regulations, standards, and internal quality criteria all rely on quantitative evaluation of Sound Pressure Level (SPL). Traditionally, this is done using a handheld sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672, placed at a specified position to read an A-weighted sound level for compliance checks and quality verification. IEC 61672 defines detailed requirements for sound level meters in terms of frequency weighting, time weighting, linearity, self-noise, and dynamic range, and classifies instruments into Class 1 and Class 2, with Class 1 having stricter requirements and being suitable for laboratory and type-approval testing. As product structures and test requirements evolve, engineers increasingly expect more than what a single handheld meter can offer: Measure multiple positions simultaneously to compare different locations or operating points Combine sound level data with spectra and octave-band analysis to quickly identify problematic frequency regions Synchronize sound level measurement with speed, vibration, temperature, and other physical quantities for NVH diagnostics Integrate sound level measurement into automated and batch test workflows, rather than relying on manual spot checks This leads to the demand for multi-channel sound level meters: systems that not only meet IEC 61672-1 Class 1 accuracy requirements, but also provide multi-channel capability, scalability, and automation. OpenTest, developed by CRYSOUND, is a new-generation acoustic and vibration test platform. Its dedicated Sound Level Measurement module, combined with CRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro front-end hardware and measurement microphones, enables multi-channel sound level measurements consistent with Class 1 sound level meters. Figure 1. From handheld sound level meters to multi-channel sound level measurement platforms IEC 61672: What Are We Actually Measuring? Meaning of Sound Pressure Level (Lp) Sound Pressure Level (SPL) is a logarithmic measure of the root-mean-square sound pressure prms relative to the reference pressure p0, which is 20 μPa in air, defined as: When prms=1 Pa, the SPL is approximately 94 dB, which is why 94 dB / 1 kHz is commonly used as the reference level for acoustic calibrators. Frequency Weighting: A / C / Z Human hearing sensitivity varies with frequency. IEC 61672 requires all sound level meters to support A-weighting, while Class 1 instruments must also support C-weighting. Z-weighting (Zero weighting, i.e. flat response) is optional. A-weighting (dB(A))Based on the 40-phon equal-loudness contour, with significant attenuation at low and very high frequencies. It is widely used in regulations and standards as an indicator correlated with perceived loudness. C-weighting (dB(C))Much flatter than A-weighting, with less low-frequency attenuation. It is suitable for evaluating peak levels, mechanical noise, and high-level events. Z-weighting (dB(Z))Essentially flat within the specified bandwidth, preserving the original spectral energy distribution, and useful for detailed analysis. While A-weighting dominates regulations, it is not a perfect psychoacoustic model. In cases involving strong low-frequency content, modulation, or tonal components, A-weighted levels may underestimate perceived annoyance.For design and diagnostic work, it is therefore recommended to combine C/Z weighting, octave-band spectra, and sound quality metrics. Time Weighting: Fast / Slow / Impulse IEC 61672 defines the following time weightings: F (Fast): time constant ≈ 125 ms, suitable for rapidly fluctuating sound levels S (Slow): time constant ≈ 1 s, suitable for observing overall trends I (Impulse): designed for impulsive signals, more sensitive to short-duration peaks Common sound level descriptors include: LAF / LAS / LAI: A-weighted sound levels with Fast / Slow / Impulse time weighting LCpeak: C-weighted peak sound level Energy-Based and Statistical Quantities: Leq, SEL, Ln IEC 61672 also defines commonly used acoustic quantities: Leq,T / LAeq,TEquivalent continuous sound level over a time period T, widely used in environmental and product noise evaluation. Sound exposure and sound exposure level: E, LE / LAE (SEL)Represent the total sound energy of an event, commonly used for aircraft, traffic, and single-event noise evaluation. Lmax / Lmin: Maximum and minimum sound levels under a specified time weighting Lpeak (typically LCpeak): Peak sound level based on peak sound pressure Statistical levels Ln (L10, L50, L90, etc.)Levels exceeded for n% of the measurement time, commonly used in environmental noise analysis. Band Levels: Octave and 1/3-Octave Bands Although octave-band filters are specified in IEC 61260, IEC 61672 aligns with them in terms of frequency response and standard center frequencies. Common analyses include: 1-octave band levels (e.g. 31.5 Hz–16 kHz) 1/3-octave band levels, offering finer frequency resolution for identifying narrow-band noise and structural resonances Together, these quantities define the full scope of sound level measurement—from instantaneous readings to time-averaged values, and from broadband levels to frequency-resolved analysis. Sound Level Measurement with OpenTest Setup: Building the Signal Chain from Source to Software Hardware Preparation Data acquisition front-endFor example, CRY5820 SonoDAQ Pro, a modular multi-channel data acquisition system supporting 4–24 channels per unit and scalable to thousands of channels. It features 32-bit ADCs, up to 170 dB dynamic range, 1000 V channel isolation, and ≤100 ns PTP/GPS synchronization accuracy, suitable for both laboratory and field acoustic and vibration testing. SensorsOne or more measurement-grade microphone sets (with preamplifiers), positioned at representative measurement or listening locations. Computer and softwareA PC with OpenTest installed and the Sound Level Measurement module licensed. Connecting Devices and Channels in OpenTest Launch OpenTest and create a new project. In Hardware Settings, click “+”; available devices (including those connected via openDAQ or ASIO) are automatically detected. Select the required acquisition devices (e.g. SonoDAQ) and add them to the project. In Channel Settings, add the microphone channels and configure sampling rate and input range. At this point, the signal chain Sound source → Microphone → DAQ → OpenTest is fully established. Calibration: Setting the Acoustic Reference To ensure absolute accuracy, each channel must be calibrated using a Class 1 acoustic calibrator. Open the Calibration dialog in OpenTest. Select the microphone channels to be calibrated. Mount the calibrator on the microphone and start calibration. Once the reading stabilizes, complete the calibration. OpenTest automatically updates the channel sensitivity so that the 94 dB SPL reference point is aligned. For comparison tests, a handheld sound level meter (e.g. CRY2851) can be calibrated using the same calibrator (e.g. CRY3018) to ensure both systems share the same acoustic reference. Measurement: Acquiring Sound Level Time Histories Switch to the Sound Level Meter module in OpenTest and select: Measurement channels Quantities to compute (Lp, Leq, Ln, etc.) Frequency weighting (A / C / Z, computed simultaneously) Typical operating conditions may include: Idle Typical load Full load For each condition: Stabilize the DUT at the target operating state. Start measurement in OpenTest. Monitor sound level time histories, octave-band plots, and FFT spectra in real time. Stop after sufficient duration and name the dataset accordingly. Each measurement is automatically saved as a dataset for later comparison and analysis. Figure 2. Multi-channel sound level measurement using OpenTest Reporting: From Data to Traceable Documentation After measurements, OpenTest's reporting function can be used to generate structured reports: Project information, DUT details, operating conditions Selected acoustic quantities (Leq, Lmax, LCpeak, Ln, etc.) Company logo and test personnel information Raw waveforms and analysis results can also be exported for archiving or further processing. Figure 3. OpenTest sound level measurement report Comparison with CRY2851 Handheld Sound Level Meter CRY2851 is a Class 1 sound level meter compliant with IEC 61672-1:2013, supporting A/C/Z weighting, F/S/I time weighting, and a full set of acoustic parameters. Comparison procedure: Environment and operating conditionsLow-background laboratory or semi-anechoic room; multiple operating states. Calibration consistencyBoth systems calibrated with the same Class 1 calibrator (94 dB or 114 dB at 1 kHz). Sensor placement and acquisitionMicrophones positioned as closely as possible at the same measurement point. Result comparisonCompare LAeq, LAF, LCpeak, and other key parameters under identical weighting and time windows. Figure 4. CRY2851 vs. OpenTest multi-channel sound level measurement Typical Applications of the Sound Level Measurement Module Consumer Electronics / IT Equipment Evaluate the impact of cooling strategies on LAeq and LAFmax Combine sound level limits with sound power measurements Integrate FFT, 1/3-octave, and sound quality metrics Automotive NVH / Interior Acoustics Multi-position sound level measurement in the cabin Comparison across driving conditions Coupling with order analysis and sound quality modules Household Appliances and Industrial Machinery Supplement sound power tests with multi-point sound level monitoring Integrate into production lines using sequence mode Identify problematic frequency bands via 1/3-octave analysis Environmental and Long-Term Monitoring Multi-point statistical sound level evaluation (L10, L50, L90) Long-term data logging and remote access If you are already familiar with handheld sound level meters, the OpenTest Sound Level Measurement module effectively upgrades them into a system that is: Multi-channel Traceable (raw data + analysis + reports) Expandable, working seamlessly with sound power, sound quality, FFT, and octave-band analysis modules, and supporting automated test workflows. Welcome to fill in the form below ↓ to contact us and book a demo and trial of the OpenTest Sound Level Meter module. You can also visit the OpenTest website at www.opentest.com to learn more about its features and application cases.

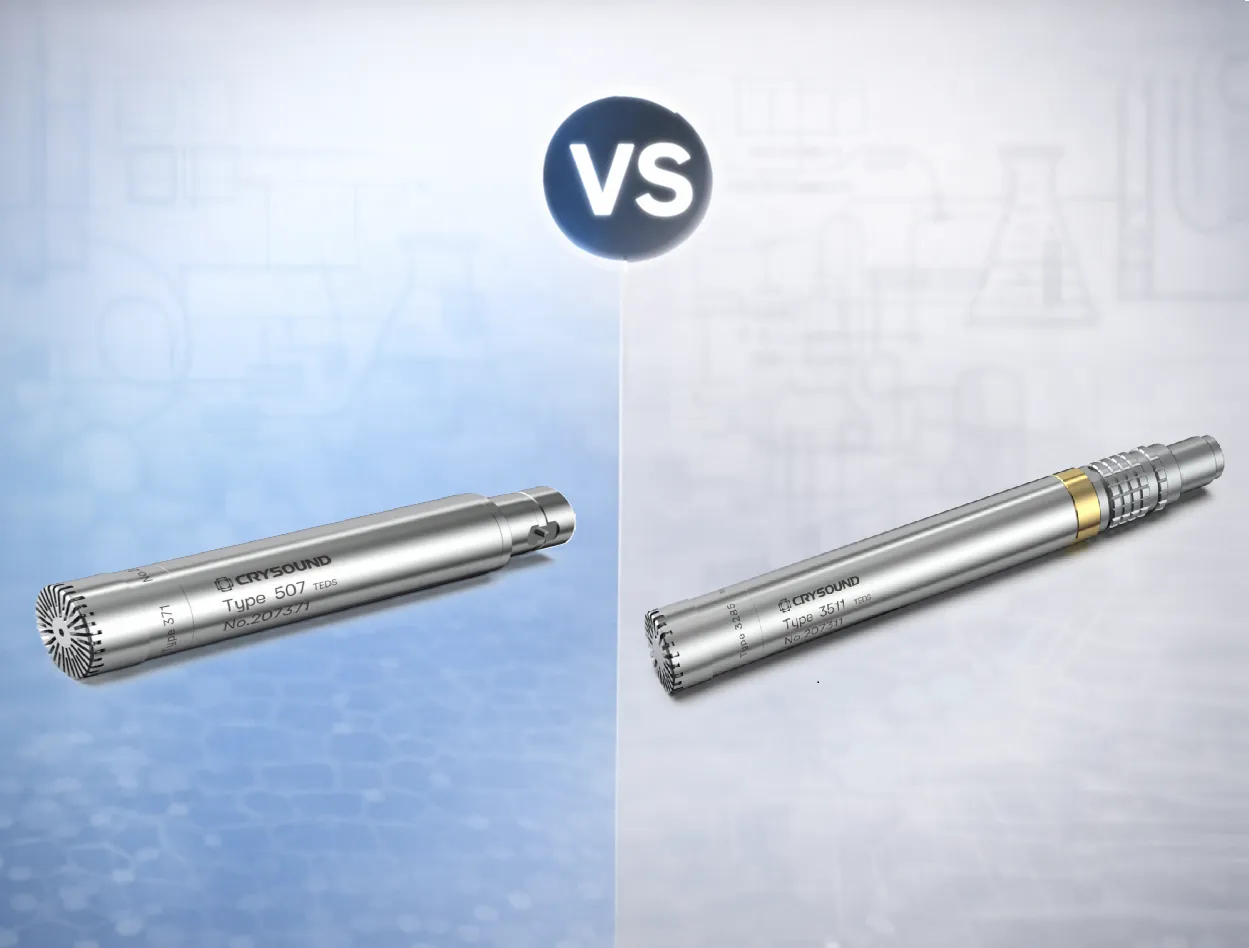

In acoustic testing, acoustic metrology, and product noise evaluation, the term measurement microphone typically refers to a condenser measurement microphone. Its signal generation relies on a polarization electric field: sound pressure changes the capacitance, and the front-end circuitry converts this change into an electrical signal. Depending on how the polarization field is provided, measurement microphones generally fall into two categories: externally polarized (polarization high voltage supplied by the measurement system, typically 200 V) and prepolarized (an internal electret provides the equivalent polarization, so no external high voltage is needed). Both can deliver high-precision measurements; the key to selection is system compatibility, environmental constraints, and maintenance cost. This article first explains how prepolarized and externally polarized microphones work and differ. It then compares power/front-end compatibility, noise and dynamic range, environmental robustness, and long-term stability. Next, it gives selection tips by scenario (metrology, approval tests, field, multichannel). It ends with a quick decision checklist. System Requirements Externally Polarized An externally polarized microphone requires a dedicated polarization unit / microphone power supply (provides 200 V polarization) to provide a stable polarization voltage (commonly 200 V) and to match the preamplifier interface (often 7-pin LEMO).This signal chain is closer to traditional metrology setups and is commonly used in laboratories and traceable calibration scenarios. Figure 1. Externally Polarized Microphone Structure Diagram Figure 2. Externally Polarized Microphone Set Prepolarized A prepolarized microphone uses an internal electret to provide equivalent polarization, so no external polarization voltage is required.System integration is simpler, making it well-suited for field work, mobile testing, and multi-channel distributed deployments. IEPE interfaces are widely used and broadly compatible; many data acquisition devices provide built-in IEPE inputs, which can significantly reduce overall equipment cost. (IEPE is the international term; some companies also refer to it as CCP or ICP.) Figure 3. Prepolarized Microphone Structure Diagram Figure 4. Prepolarized Microphone Set Engineering Trade-offs From an engineering application perspective, the main differences are: System compatibility: Externally polarized microphones depend on 200 V polarization and specific front-end/interfaces; prepolarized microphones place fewer requirements on the front-end and enable more flexible integration. Environmental robustness: High humidity, condensation, dust, oil mist, and similar environments can amplify insulation and leakage issues; prepolarized microphones often achieve more stable results. For high-temperature applications, carefully verify the model's temperature limit and long-term drift data; externally polarized microphones are more commonly used where high-temperature stability and metrology-grade requirements are prioritized. Deployment and maintenance: Prepolarized solutions avoid high-voltage risk, deploy faster, and typically cost less at scale. Externally polarized setups demand higher standards for cleanliness, insulation, connector reliability, and troubleshooting capability. Selection Guidelines Front-End and Power Architecture If your existing front-end natively supports 200 V polarization and you have long used that metrology signal chain, prioritize externally polarized microphones to minimize retrofit effort and compatibility risk. If your front-end does not support polarization high voltage, or your system is mainly based on constant-current powering (e.g., CCLD/IEPE), prioritize prepolarized microphones for higher deployment efficiency and broader compatibility. Environmental Constraints (Humidity / Contamination / Temperature) For high humidity, condensation, dust, or oil mist in the field: prioritize prepolarized microphones or models with protective designs, and pay close attention to connector and cable protection. For high temperature or thermal cycling: base the choice on datasheets and stability data. Both externally polarized and high-temperature prepolarized models may be suitable, but you must verify the temperature limit and drift specifications. Align the Key Performance Targets Low-noise measurement: focus on equivalent self-noise, front-end noise, cable length, and shielding/grounding strategy. High SPL / shock measurement: focus on maximum SPL, distortion, overload recovery, and front-end input headroom (capsule size selection is often more critical than polarization method). Consistency / traceability: focus on calibration system, long-term drift, temperature coefficient, and maintenance interval. Budget and Total Cost of Ownership If budget is tight, channel count is high, or you need rapid scaling: prioritize prepolarized microphones. Without external polarization high voltage, the measurement chain is simpler and total investment is usually lower. If an externally polarized chain is required: include the external polarization power supply/adapter as a mandatory budget item. In addition to the microphone and preamplifier, a stable 200 V polarization supply is required, and the polarization supply can be costly. For multi-channel deployments, total cost rises significantly with channel count. If the laboratory already has sufficient channels of external polarization supplies, the incremental cost can be much lower. Conclusion There is no absolute “better” option between prepolarized and externally polarized microphones. A more reliable engineering approach is to first define the measurement chain and environmental constraints, then finalize the model selection using key metrics such as noise, dynamic range, consistency, and traceability. You are welcome to learn more about microphone functions and hardware solutions on our website and use the “Get in touch” form to contact the CRYSOUND team.